Against Cosmological Idealism

Why Murray’s Argument Revives Creation Ex Nihilo

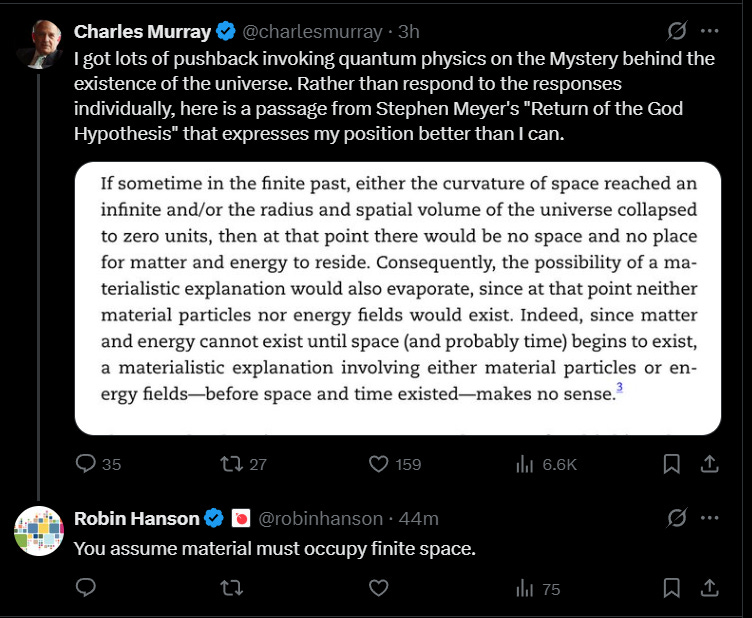

Charles Murray, quoting Stephen Meyer, presents a familiar metaphysical move: if the universe once had no space or time, then there could be no matter or energy to “reside” anywhere. Therefore, materialistic explanations must fail, leaving divine or immaterial causation as the only coherent alternative.

Robin Hanson’s laconic response—”You assume material must occupy finite space”—is both a devastating critique and a modern corrective. It exposes that Meyer’s reasoning rests on a pre-relativistic metaphysics: the assumption that matter and energy are in space rather than constitutive of it.

The Error of the Container Model

Meyer’s argument assumes what physicists discarded over a century ago: the idea of space as a passive container in which matter exists. Under Newton’s absolute space, this made sense. But in general relativity, spacetime is not a stage—it is a dynamic actor co‑defined with the distribution of mass-energy. Matter tells space how to curve; space tells matter how to move. Remove matter, and the concept of “empty space” becomes ill‑defined.

By treating space as an external prerequisite for existence, Meyer commits what might be called the finite fallacy: assuming that because something is spatially extended now, it must always have been extended somewhere. But if spacetime itself is emergent from quantum fields or informational relations, then the question of where matter was “before space” is incoherent—like asking where the color blue was before light existed.

Matter Without Place

Modern physics allows for ontologies where matter does not occupy finite space:

Quantum fields exist not in space but as the substrate from which space emerges. The geometry of spacetime may itself be a statistical effect of entanglement patterns.

The wavefunction of the universe in the Wheeler–DeWitt formalism is defined over configuration space, not physical space. It encodes all possible spatial geometries, none of which require pre‑existing extension.

Pre‑geometric theories—loop quantum gravity, causal set theory, and AdS/CFT duality—treat spacetime as a derived phenomenon from discrete or relational information.

From these perspectives, “matter before space” is not nonsense; it’s physics. What Meyer calls incoherent is merely unfamiliar.

Philosophical Stakes

Meyer and Murray are not defending physics—they are defending a metaphysical intuition: that being must have location. Hanson rejects this intuition entirely. His point is not theological but ontological. If material existence is defined by the capacity to generate structure, relation, and conservation, then it need not be spatial. Spacetime could be one emergent mode of material relation, not its ground.

This reorientation dissolves the false dichotomy between “material” and “immaterial.” Once matter is understood as pattern rather than substance, information and energy become natural continuations of physical law, not exceptions requiring divine intervention.

The Coherence Criterion

Meyer’s reasoning fails the coherence test because it projects finite intuitions into domains where they no longer apply. To say “material explanation makes no sense before space” is to conflate explanation with visualization. The fact that we cannot picture non‑spatial existence does not make it incoherent. The map of space-time is a product of the territory, not its prerequisite.

Hanson’s one‑line rebuttal captures this entire insight: material does not need a finite place—it is the process that gives rise to places.