Against Utopia

Agent-Relative Value and the Limits of Political Closure

This post explains The Incoherence of Utopia Under Agent-Relative Value without formal notation. The underlying paper develops its claims using explicit definitions and constraints; what follows translates those results into conceptual terms while preserving their structural content.

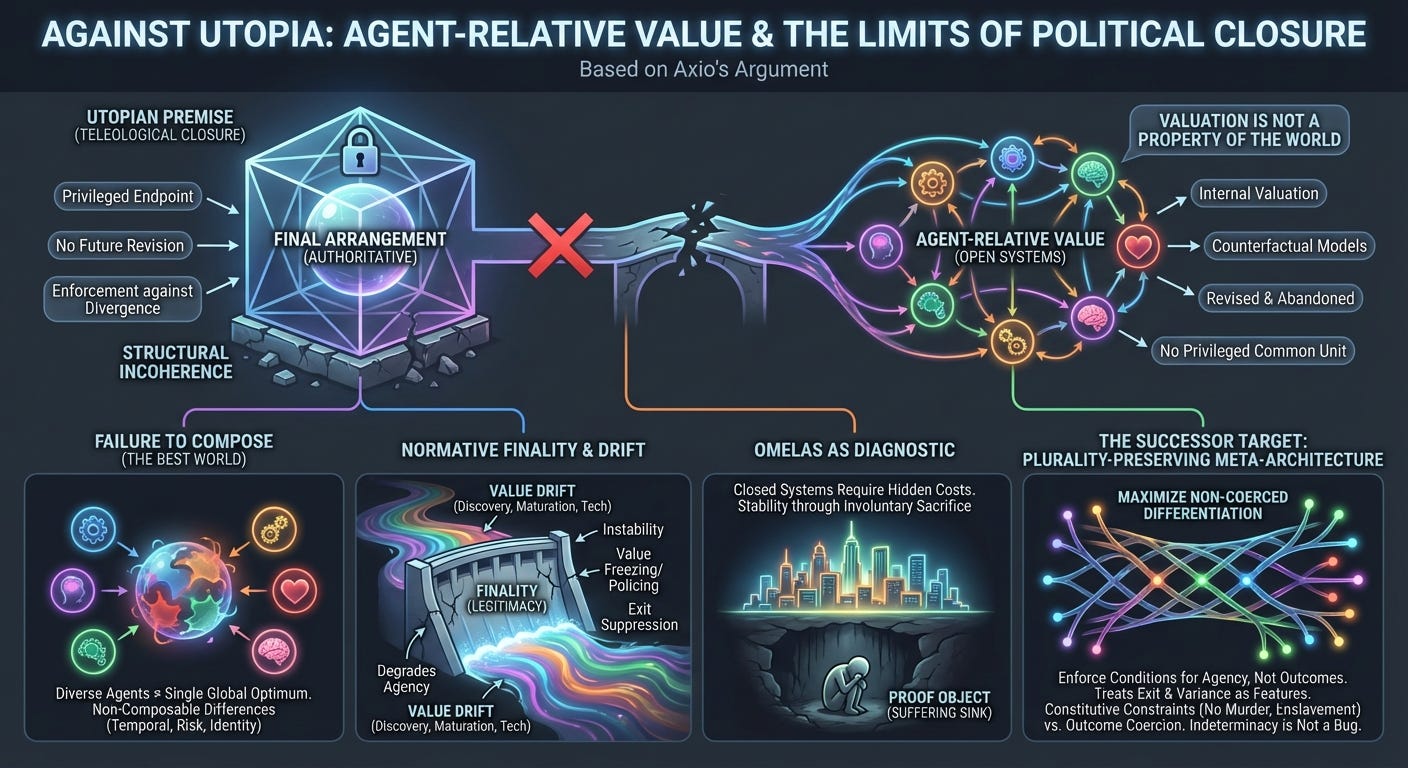

Utopia persists because it flatters a deep human appetite: the belief that social order has a natural terminus, a final arrangement whose legitimacy can be asserted once and then merely administered. The vocabulary varies—religious eschatology, revolutionary end-states, technocratic “optimal governance,” or the polite modern version where the word utopia is avoided while its structure remains intact. In every case, the same idea is doing the work: there exists an arrangement that deserves to be treated as final.

Axio rejects that idea at the level where it is usually left unexamined: the typing discipline of value. Once value is treated as agent-relative—generated, revised, and sometimes abandoned by agents—the concept of a final, authoritative world-design ceases to denote a coherent target. The failure is not best understood as moral disagreement, historical naïveté, or implementation difficulty. It is a structural incoherence, comparable to demanding a single global coordinate system on a curved manifold or asking a compiler to resolve an ambiguity the type system refuses to make meaningful.

Utopia, in the relevant sense, is ill-typed.

The Premise Utopianism Requires

Most debates about utopia take place inside a tacit frame: assume “the good society” exists, then argue about its content and the path to it. That frame quietly commits to a stronger proposition than it admits:

The space of possible social arrangements contains a privileged endpoint.

That endpoint can be treated as authoritative over future revision.

The first proposition makes utopia a destination. The second turns it into a political program, since authority over revision implies enforcement against divergence.

The language can be softened—“stable equilibrium,” “ideal constitution,” “end of history,” “the system once properly designed.” The structure remains: teleological closure. A claim that the moral and political search space can, in principle, be closed.

Axio’s claim is that closure collides with the ontology of agency once value is agent-relative. The collision is structural, not contingent.

Agents as Sources of Value

An agent is a system capable of forming counterfactual models of possible futures, evaluating them according to internal criteria, and acting in ways that influence which futures become real. This definition is deliberately minimal. It assumes neither rationality nor consistency nor moral virtue.

What matters is the implication: valuation is not a property of the world. It is an activity internal to agents.

This seems trivial until one notices how much political philosophy proceeds as if the opposite were true. Moral and utopian rhetoric often treats “the good” as something out there in the world, waiting to be discovered and instantiated. Under agent-relative value, goodness is a relation between an agent and a world-history; it is not an intrinsic label attached to a state of affairs.

Once this shift is made, several conveniences disappear at once:

There is no privileged common unit of value across distinct agents.

There is no default rule for aggregating valuations into a single authoritative ordering.

Disagreement ceases to be a regrettable noise term and becomes a structural feature of heterogeneous agency.

This is the first fracture line utopia crosses without noticing.

Why “The Best World” Fails to Compose

Utopian projects often aspire—explicitly or implicitly—to a world that is “best” in a global sense. Even when pluralism is acknowledged, it is typically assumed that pluralism can be domesticated: translate diverse values into a common calculus, then compute the best arrangement.

That assumption is the composability error.

Agents differ in ways that are not reducible to parameter tuning. They differ in temporal perspective, risk posture, identity commitments, aesthetic standards, moral side-constraints, and meta-preferences about how preferences themselves may be formed or revised. A governance system can bargain across such differences, negotiate compromises, and coordinate action. What it cannot do, absent extra structure, is produce a single globally authoritative ranking of world-histories that remains stable under value revision.

Any mechanism that claims to do so has only a few available moves:

It can grant dictatorial authority.

It can choose a weighting scheme that feels arbitrary to the agents themselves.

It can impose convergence by editing, excluding, or suppressing divergence.

These are not unfortunate edge cases. They are the only ways to force a single global optimum out of heterogeneous valuation once value is internal.

Strong utopia—the idea of a world that is optimal for all agents—therefore fails as a coherent specification unless one abandons agency or pluralism. Under agent-relative value, it is not merely unrealistic. It is mis-typed.

Normative Finality: The More Dangerous Form

Since maximal satisfaction is obviously strained, many utopian instincts retreat into a weaker posture: they stop promising the best possible world and promise instead legitimacy. The claim becomes:

This arrangement is the rightful endpoint; further structural revision is illegitimate.

This is normative finality, and it is the form of utopia that actually governs institutions. Constitutions are sacralized. Systems are declared “solved.” Disagreement is reframed as error, immaturity, or bad faith. The aspiration is not happiness but closure.

Once value drift is taken seriously, the instability of this posture becomes unavoidable.

Value Drift and the Cost of Stability

Agents are not static preference tables. They are developmental processes embedded in learning, culture, physiology, and history. Values change through discovery, maturation, reflection, imitation, trauma, and technological transformation. None of this privileges novelty for its own sake; it merely recognizes that agents who remain agents retain the capacity to revise or reaffirm their values without external foreclosure.

A final arrangement faces the drift problem immediately. Even if it aligns with prevailing values at one moment, it must remain authoritative as those values evolve. To do so, it must deploy stabilizers:

Value freezing: constraining agents’ capacity to revise identities or commitments.

Value policing: suppressing divergence through correction, stigma, or punishment.

Exit suppression: preventing dissidents from leaving or forming alternatives.

These strategies differ in tone and severity. Structurally, they are the same. They convert dynamic agents into administrable objects.

A utopia that remains final under drift becomes, over time, a machine for degrading agency.

Omelas as Structural Diagnostic

Omelas is usually treated as a moral puzzle: can the happiness of many justify the suffering of one? That framing invites utilitarian arithmetic. It also misidentifies the function of the story.

The suffering child is not a dilemma. The child is a proof object.

Omelas reveals the architecture of a closed system whose stability depends on a standing asymmetry—an irreducible sink where costs are concentrated, consent is irrelevant, and resistance is structurally impossible. The child’s suffering anchors the equilibrium.

The walkers are often psychologized as purists or sentimentalists. A cleaner interpretation is available: they recognize that the system’s stability requires involuntary sacrifice, and they refuse to authorize it through participation.

This is why Omelas generalizes. Replace the child with any hidden class that bears stabilizing cost—prisoners, permanent undercasts, outsourced labor, invisible risk pools. The surface changes; the structure remains. Closed designs require sinks.

Closure Versus Agency

The contradiction can now be stated plainly.

Utopia requires closure: convergence to an arrangement that claims final authority.

Agency requires openness: revision, deviation, experimentation, and future differentiation.

A system cannot preserve both indefinitely.

If closure is preserved, agency is progressively constrained.

If agency is preserved, closure erodes under drift.

The long-run outcome is not accidental tyranny. It is structural: worlds that remain utopian in the weak sense tend toward conditions under which agency ceases to be well-defined.

The Successor Target: Plurality-Preserving Meta-Architecture

Rejecting utopia does not imply nihilism or resignation. It changes the design target.

The successor is a plurality-preserving meta-architecture: a framework that enforces the conditions under which agency can exist while leaving substantive outcomes open. In practice, this is close to what defenders of open societies, constitutional liberalism, and neutral governance often gesture toward at their best moments—though here the justification is structural rather than moralistic.

The design objective becomes:

Maximize non-coerced future differentiation subject to agency-preserving constraints.

Such a framework does not optimize a single vision of the good life. It does not demand value convergence. It treats exit, variance, and disagreement as features of a healthy system rather than pathologies to be eliminated.

This position resembles Nozick’s “meta-utopia,” though the route is different. Here, plurality is forced by non-composability under value drift, not derived from rights axioms.

Constitutive Constraints, Made Concrete

The standard objection arrives reliably: enforcing non-coercion is itself coercive. This is meant to collapse the distinction between neutral frameworks and outcome-imposing utopias.

The objection trades on ambiguity.

There is a difference between:

Outcome coercion: enforcing substantive ends or lifestyles.

Constitutive constraints: enforcing the conditions that keep agency from being erased.

Forbidding murder, enslavement, or conquest preserves the possibility of agency. Mandating that everyone adopt a particular religion, career, or aesthetic imposes an outcome. The former constrains domination; the latter substitutes an external optimizer for individual choice.

A system that refuses to enforce constitutive constraints does not remain neutral. It simply defaults to domination by whichever agents are most willing to coerce.

Neutrality is not the absence of enforcement. It is the enforcement of the conditions under which choice remains possible.

Indeterminacy Is Not a Bug

No framework can algorithmically resolve every boundary case—monopoly, redistribution, regulation, collective risk—without importing substantive value commitments. Many political theorists and system designers crave a clean decision procedure that classifies every policy as either constitutive or outcome-imposing. Under dynamic agency, such a procedure does not exist.

This indeterminacy is not a flaw. It is a consequence of governing evolving agents under uncertainty.

Political contestation persists in plurality-preserving architectures. What changes is the constraint: contestation itself must not collapse into domination.

Postscript

Utopia fails for reasons that have nothing to do with cynicism about human nature or pessimism about cooperation. It fails because value, once recognized as agent-relative, cannot be frozen without dissolving the very agency that gives value its meaning. Heterogeneous agents do not compose into a single authoritative optimum, and arrangements that claim finality must eventually defend themselves against drift through mechanisms that substitute administration for choice.

The utopian impulse persists because it mistakes world-states for moral objects rather than treating agents as the loci of valuation whose trajectories diverge over time. When this mistake is corrected, the problem of political design shifts. The central question is no longer which world deserves to be called perfect, but which kinds of frameworks can host ongoing revision while resisting domination patterns that erase the conditions of agency itself.

Plurality-preserving meta-architectures are an attempt to answer that question without invoking teleology or moral finality. Utopia, by contrast, presupposes closure where none can coherently exist.