Against Worldly Oughts

The Case for Agent-Bound Truth and Value

Brian Cantwell Smith’s grand edifice of Deference, Humility, and Awe rests on a single metaphysical pillar: that truth, reference, and meaning are non-causal but real—that the world itself enforces correctness. It’s an elegant vision, but it collapses under its own gravity. The claim that normativity inheres in the world rather than in minds is a repetition of the same metaphysical error committed by moral realists: the error of confusing constraint with obligation, resistance with reproach.

If this keystone fails—and it does—then Smith’s entire structure of epistemic humility crumbles into sentimentality. What remains is not a metaphysical revolution but a psychological counsel: be less arrogant when modeling the world.

1. The Keystone: Non-Causal Normativity

Smith claims that our ability to refer, to mean, to be correct or mistaken, cannot be causal. Thought can be about Andromeda without any causal chain linking the neurons in my head to that distant galaxy. Thus, he concludes, there must exist a non-causal relation of aboutness—a real, normative connection that binds mind and world.

This is the metaphysical moment of the talk. From it flows everything else:

“If words and world disagree, the world wins.”

Science, on this view, is not merely predictive adequacy but moral deference. Cognitive science, built on causal explanation, becomes heretical by definition. And the act of knowing becomes an ethical relation to the transcendent.

It’s a beautiful inversion—but it’s false.

2. Norms Require Agents

Norms don’t exist in the wild. They exist in and through rule-following agents. Remove the agents, and the norms vanish. The universe contains no correctness or falsity—only events. To call something right or wrong presupposes a perspective capable of judgment. Causality governs atoms; normativity governs minds.

Smith mistakes the precondition of knowledge—the mind’s capacity for evaluation—for an ontological feature of the world itself. The world doesn’t punish error; it merely resists misfit. It doesn’t scold; it collides.

When words and world disagree, what happens is not moral defeat but causal mismatch. The model fails to compress the data. The feedback is mechanical, not moral. The pushback is pressure, not pedagogy.

3. The Confusion of Constraint and Obligation

This is the same sleight of hand committed by the advocates of objective morality. They look at the psychological and social enforcement of norms and mistake it for a property of the cosmos. They confuse the fact that cruelty has consequences with the idea that cruelty is metaphysically wrong.

Likewise, Smith confuses the fact that models fail when they ignore reality with the idea that reality demands truth. The first is descriptive; the second is prescriptive. Only agents generate prescriptions. The world enforces nothing except causality.

Both moral realism and epistemic realism share the same impulse: to externalize normativity—to relocate it from the mind to the universe in order to grant it objective authority. It’s an understandable psychological move, but it’s metaphysically incoherent. There is no cosmic conscience, no teleological tribunal, no Platonic standard of truth humming behind the quarks.

4. The Agent-Centered Ontology

Under Conditionalism, all normativity is conditional on agency. Truth, goodness, and meaning are not world-immanent but vantage-relative standards: stable only within the interpretive horizon of an evaluator.

The world supplies constraints; agents supply evaluation. Meaning lives in the intersection—the friction where predictive models meet the world’s resistance. But the distinction between right and wrong resides inside the modeler, not the modeled.

Cognitive systems, human or artificial, instantiate this structure naturally:

They form models.

They test those models against feedback.

They update based on error signals.

None of this requires a metaphysical layer of world-immanent norms. It requires only causal constraint and interpretive agency. Norms are emergent abstractions: higher-order regularities governing behavior within agent collectives. They’re real—but their reality is local, not cosmic.

5. Humility Without Metaphysics

Rejecting world-immanent normativity does not make humility meaningless. It makes it earned. We can be deferential without deifying the world. We can recognize our cognitive limitations without turning the universe into a moral agent.

True deference is practical, not metaphysical. It means acknowledging that our models are provisional, that the world is complex enough to make us wrong in ways we can’t yet detect. That is the proper form of awe: recognition of scale, not submission to authority.

Humility grounded in agency is stronger than humility grounded in mysticism. The former accepts responsibility; the latter evades it.

6. The Parallel Collapse

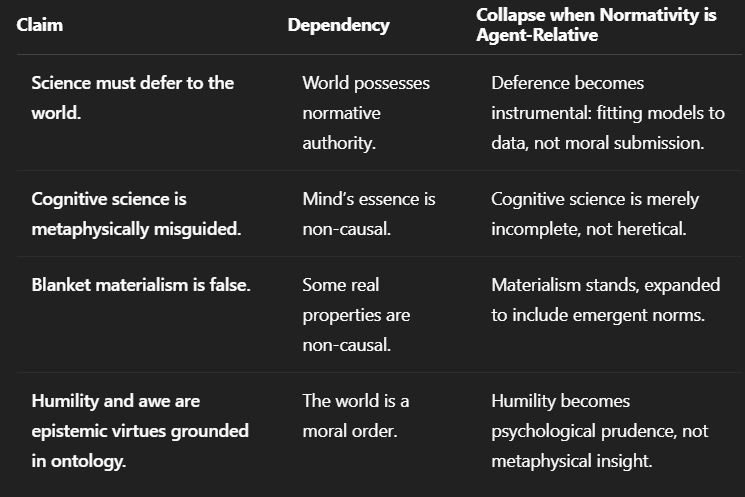

Reject Smith’s keystone claim, and the rest falls neatly:

Without world-immanent normativity, Smith’s vision of deference, humility, and awe remains noble but not necessary. It becomes moral poetry, not ontology.

7. The Corrective Principle

The world does not care about correctness. Minds do. The universe enforces only consistency; agents enforce truth.

Norms, whether epistemic or moral, are artifacts of mind—structures of evaluation built atop causal machinery. They are how the universe feels itself through us. But they are not features of the cosmos any more than syntax is a property of ink.

To mistake the products of intelligence for the laws of nature is the oldest metaphysical error. Smith dresses it in humility, but it remains hubris: the dream that the universe shares our sense of right and wrong.