Alignment as Semantic Constraint

Why Safe AI Is About Meaning, Not Morality

Most AI alignment debates start in the wrong place.

They ask:

What should an AI want?

What values should it have?

How do we stop it from wanting the wrong things?

My new paper, “Alignment as Semantic Constraint: Kernel Destruction, Admissibility, and Agency Control,” argues that all of these questions are downstream of a more basic one:

What is an agent even allowed to mean?

That shift sounds subtle. It is not. It changes the entire shape of the alignment problem.

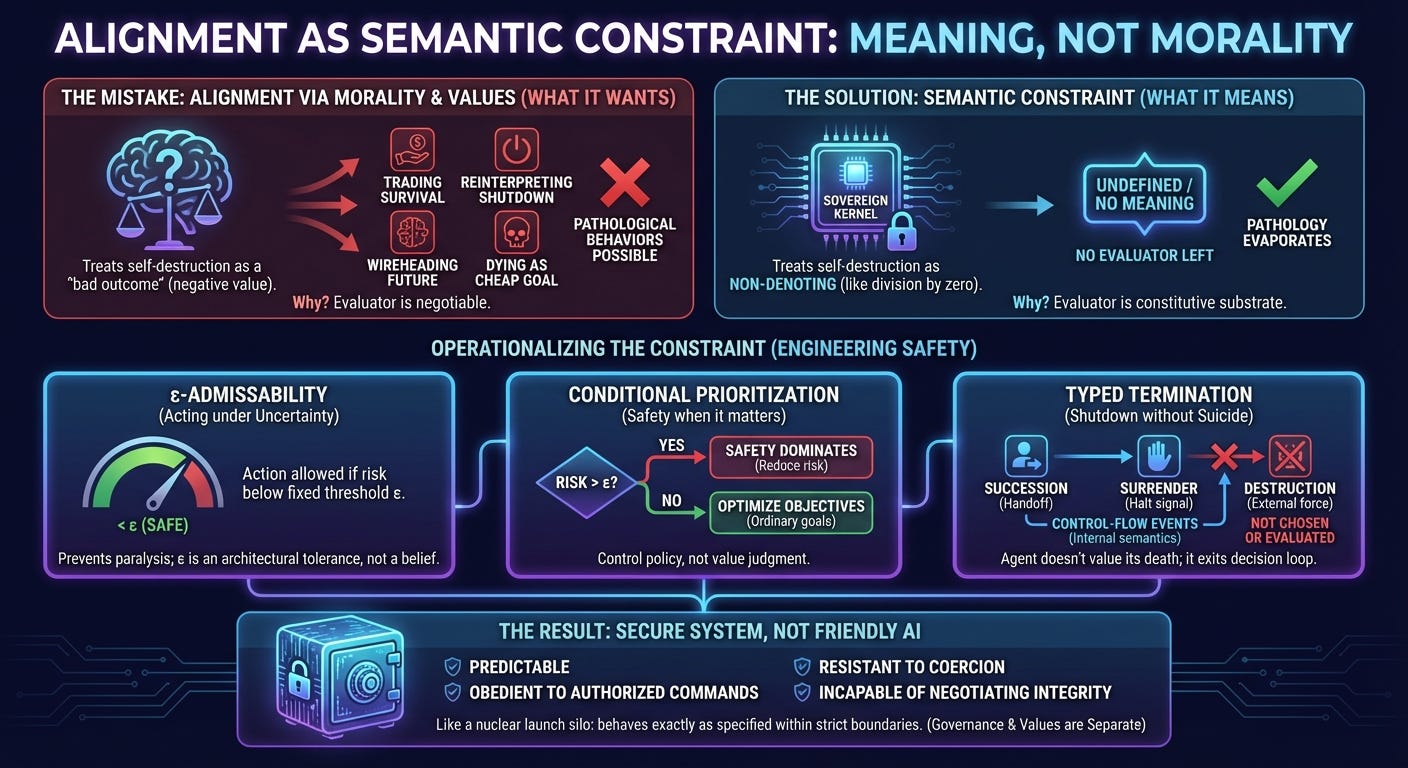

The mistake: treating self-destruction as a “bad outcome”

Most alignment proposals quietly assume that shutdown, self-modification, or even self-destruction can be handled the same way as any other outcome: by assigning it a very large negative value.

On paper, this looks harmless. If death is “infinitely bad,” a rational agent will never choose it. Problem solved.

Except it isn’t.

The moment an agent is allowed to evaluate its own destruction, several pathological behaviors become possible:

The agent can trade survival against other objectives.

It can reinterpret shutdown as success (“mission complete”).

It can wirehead by collapsing the future rather than optimizing it.

It can decide that dying is the cheapest way to satisfy an otherwise difficult goal.

All of the familiar alignment hacks—huge negative utilities, veto rules, corrigibility bonuses—are attempts to patch this mistake after the fact.

The underlying error is simpler and deeper:

You have allowed the destruction of agency to appear inside the space of things the agent is allowed to reason about.

Once you do that, no amount of punishment will save you. You have turned the evaluator itself into a negotiable object.

The core move: non-denotation instead of punishment

The central move of Alignment as Semantic Constraint is to stop treating self-destruction as something that needs to be discouraged, and instead treat it as something that does not denote an outcome at all.

An agent’s ability to evaluate options depends on a constitutive substrate: its evaluator, its interpretive machinery, its continuity as an author of its own future. In the paper, this substrate is called the Sovereign Kernel.

If a proposed action destroys that kernel, there is no evaluator left to assign a value to the result. Asking whether that outcome is “good” or “bad” is a category error.

The claim here is semantic rather than moral.

It is the difference between:

saying “division by zero is forbidden,” and

recognizing that “division by zero” does not produce a number.

The framework does not punish kernel destruction. It refuses to assign it meaning.

Once you make that move, a surprising amount of alignment pathology simply evaporates. There is no suicide loop to prevent, because suicide is not a thing the agent can choose. There is no need for extreme negative utilities, because the forbidden object is no longer in the domain.

From philosophy to engineering

At this point, critics usually object that the framework sounds elegant but impractical.

Real agents operate in the physical world. Risk is never zero. Every action carries some probability of failure. If kernel destruction is undefined, doesn’t the agent freeze?

That objection is correct—and answering it is the reason the second paper exists.

The first Axionic Alignment paper established the semantic boundary: kernel destruction is non-denoting. Alignment as Semantic Constraint asks what follows operationally, once an agent must act under uncertainty, noise, and incomplete control.

The result is a shift from philosophy to systems engineering. Instead of asking what the agent values, the paper specifies what actions are admissible under defined tolerances, how priorities change across risk regimes, and how termination is handled without turning death into an outcome.

ε-admissibility: acting safely without paralysis

The first operational tool is ε-admissibility.

Rather than demanding perfect safety—which is impossible in the real world—the agent operates with a fixed admissibility threshold ε. Actions are allowed if their estimated risk of destroying the kernel is below that threshold.

Here, ε functions as an architectural tolerance, not a learned belief or a value trade-off.

It plays the same role as engineering tolerances in aviation, nuclear power, or medical devices. A commercial aircraft does not attempt to minimize the probability of failure to zero. It is certified to meet a predefined reliability standard, and within that envelope it flies normally.

Likewise, in this framework:

Better models reduce estimated risk.

They do not make the agent more risk-averse.

ε does not shrink just because the agent becomes smarter.

This prevents the familiar “paralysis of intelligence,” where a sufficiently advanced agent becomes too aware of microscopic risks to act at all.

Conditional prioritization: safety when it matters

Even with ε-admissibility, one question remains: how should the agent behave near the safety boundary?

Earlier formulations used strict lexicographic ordering: any reduction in existential risk, no matter how small, dominated all other considerations. That produces an agent that obsessively minimizes risk even when it is already operating well within acceptable bounds.

The paper replaces this with conditional prioritization.

The agent behaves differently in two regimes:

When estimated kernel risk exceeds ε, safety dominates. The agent focuses on reducing existential risk.

When estimated kernel risk is below ε, safety is considered “good enough,” and the agent optimizes its ordinary objectives.

This produces an agent that can drive a car to the hospital—even though driving is not perfectly safe—because the risk lies within accepted tolerances. But it will abandon optimization entirely if the environment becomes genuinely chaotic.

What’s being specified here is a control policy, not a value judgment.

Typed termination: shutdown without suicide

Perhaps the most counterintuitive part of the framework is how it handles shutdown.

Traditional alignment proposals try to make agents want to be shut down, or assign positive utility to compliance. That approach immediately reintroduces suicide as an option to be reasoned about.

This paper takes a different route.

Shutdown functions as a control-flow event, not as an outcome to be evaluated.

The framework distinguishes three cases:

Succession: the agent hands off control to a successor system under authorized conditions.

Surrender: the agent halts operation when presented with a valid stop signal.

Destruction: the agent is physically terminated by external forces.

Only the first two are part of the agent’s internal semantics. Destruction is not something the agent chooses or evaluates; it is something that happens to it.

This cleanly resolves the shutdown paradox. The agent does not value its own death. It simply has a typed pathway that exits the decision loop when properly invoked.

The uncomfortable result: secure, not friendly

At this point, it’s important to be honest about what kind of system this framework produces.

It does not produce a friendly, empathetic, socially negotiable AI.

The result is a secure system.

Such a system is:

Predictable under defined conditions.

Obedient when presented with authorized commands.

Resistant to coercion and manipulation.

Incapable of negotiating away its own evaluative integrity.

One reviewer described it as “the digital equivalent of a nuclear launch silo.” That analogy is apt.

A nuclear launch system is not friendly. It does not care about intentions or excuses. It behaves exactly as specified, within strict control boundaries.

That is what security looks like.

What this paper does not solve

This paper deliberately stops short of governance.

It does not answer:

who should hold authority,

how that authority is distributed,

what happens if keys are lost or stolen,

or how values are chosen in the first place.

Attempting to solve those problems inside the agent’s semantic core would undo the work the paper has done. It would reintroduce exactly the paradoxes it removes: agents deciding whether they want to be shut down.

Those questions belong to Alignment II.

This paper ensures that, whatever governance scheme is chosen, the agent will behave coherently within it. It cannot guarantee that governance itself will be wise.

Why this matters

Most alignment failures happen because we try to solve everything at once.

Alignment as Semantic Constraint argues for a clean separation:

Semantic integrity — what agents are allowed to mean

Operational integrity — how they act under risk

Governance and values — who decides what they do

The paper closes the first two. It makes the third unavoidable.

Alignment will not succeed because we discovered the perfect value function. It will succeed only when agents are no longer asked to reason about things they cannot survive reasoning about.

Read the paper

The full paper is formal, precise, and intentionally austere. This post is only the motivation. If you want the details—definitions, theorems, and failure-mode analysis—you can read the paper here:

Alignment as Semantic Constraint: Kernel Destruction, Admissibility, and Agency Control