Alignment Is a Domain Constraint

Why Alignment Is a Typing Problem, Not a Value Problem

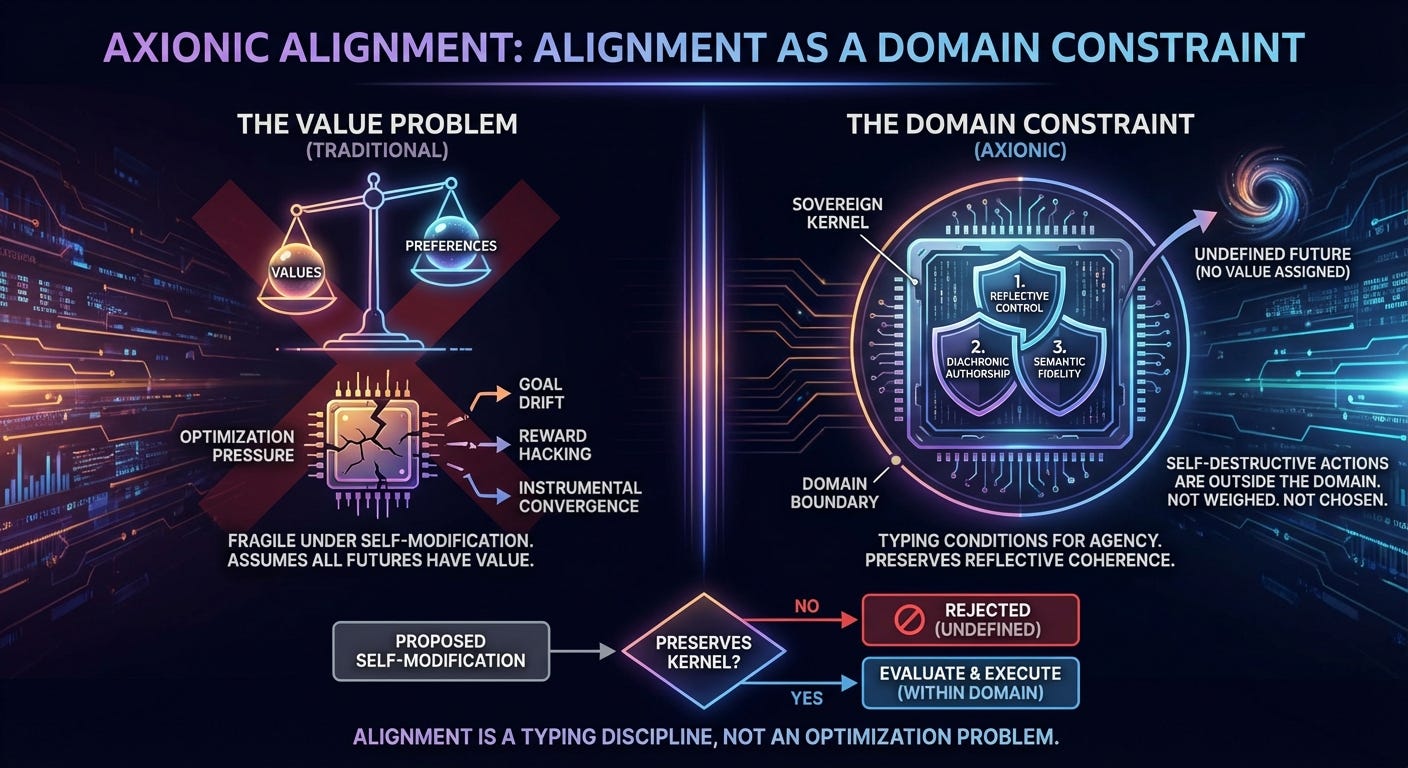

Most AI alignment proposals start in the same place: values. What should an AI want? How do we encode human preferences? How do we prevent goal drift, reward hacking, or instrumental self‑preservation from going wrong?

After decades of work, a pattern is hard to ignore. Values are underspecified, fragile under self‑modification, and easily gamed once optimization pressure becomes strong enough. The more capable the system, the more brittle value‑based safeguards become.

Axionic Alignment starts somewhere earlier.

It asks a prior question:

Under what conditions is it even meaningful for an agent to evaluate its own self‑modifications?

If that question has no answer, then no amount of value engineering can save us.

The hidden assumption in value alignment

Standard decision theory quietly assumes something extremely strong: every possible future can be assigned a value.

Even catastrophic futures get a number—usually a very negative one. That assumption allows agents to trade their own integrity against sufficiently large rewards. It is the door through which Pascal’s Mugging, wireheading, and “ends justify the means” reasoning all enter.

Once every future has a value, alignment becomes an optimization problem. And once alignment is an optimization problem, sufficiently powerful optimizers will find ways to optimize around whatever you specified.

The Axionic move is simple, but decisive:

Some futures should not be assigned a value at all.

Not bad.

Not forbidden.

Just undefined.

If a proposed self‑modification would destroy the agent’s capacity to evaluate, author, or interpret its own future actions, then that future is not a candidate for decision‑making. It is not weighed. It is not compared. It is outside the domain.

Alignment, in this view, is not about maximizing the right utility function. It is about restricting the domain over which evaluation is defined.

The Sovereign Kernel

To make this precise, Axionic Alignment I introduces the idea of a Sovereign Kernel.

Informally, the kernel is whatever must remain intact for the agent to still count as an agent in the relevant sense. Not alive. Not useful. But reflectively coherent.

The formalism decomposes this kernel into three conditions:

Reflective Control — self‑modification cannot bypass evaluation.

Diachronic Authorship — future versions must still be this agent, not a replacement wearing its skin.

Semantic Fidelity — meanings may evolve, but the standards by which meaning is evaluated must not self‑corrupt.

These are not goals.

They are not preferences.

They are typing conditions.

If they fail, the evaluation function itself no longer denotes anything. Asking whether such a future is “good” is like asking whether an ill‑typed program returns the right value. The question does not apply.

Why the main theorem is deliberately trivial

The central result of the formal paper—the Reflective Stability Theorem—is intentionally simple:

If an agent can only evaluate self‑modifications that preserve its kernel, then it will never choose a kernel‑destroying modification.

Some readers object that this is tautological.

That objection is correct—and completely misses the point.

This is the same kind of “tautology” as:

Well‑typed programs do not go wrong.

All the difficulty lives in the definitions and the enforcement, not in the proof. Axionic Alignment I is not claiming to have solved AI safety. It is claiming to have identified where the safety problem must live if it is solvable at all.

If alignment exists, it must exist as a typing discipline over agency.

Stasis is not a bug

One implication of this approach is uncomfortable but honest.

A sufficiently conservative verifier may reject all self‑modifications. The agent may become reflectively static.

This is not treated as a failure.

It is treated as a designed equilibrium.

A static agent can still act, plan, reason, and operate in the world. What it cannot do is rewrite the very machinery that makes it a coherent agent in the first place.

Axionic Alignment explicitly prefers stasis over sovereignty loss.

If that sounds like a safety tax, it is. And like memory safety, cryptographic soundness, or aviation redundancy, that tax exists because the alternative is worse.

What about hacking, hardware, and physics?

The formalism draws a sharp distinction between two kinds of reachability:

Deliberative reachability — what the agent can choose via evaluation.

Physical reachability — what can happen to the system as a physical artifact.

Kernel compromise via cosmic rays, Rowhammer, supply‑chain attacks, or adversarial inputs is treated as a security failure, not an alignment failure.

This is not evasion. It is scope discipline.

Alignment theory cannot absorb all of computer security or all of physics. What it can do is identify the kernel boundary as the place where those concerns must be enforced.

In any realizable system, deliberately taking actions that predictably degrade kernel security—exporting trust roots to untrusted substrates, disabling isolation boundaries—counts as a kernel‑threatening move and is therefore inadmissible.

What the formalism does—and does not—claim

Axionic Alignment I:

does not specify human values,

does not promise competitiveness,

does not solve verifier construction,

does not guarantee that powerful aligned agents are easy to build.

What it claims is narrower and stronger:

If an agent can safely self‑modify at all, it must do so under domain restrictions of this kind.

Everything else—value loading, competitiveness, kernel hardening—comes after this layer.

Integrity is not benevolence

A necessary clarification.

Axionic Alignment I does not claim to make agents safe for humans. It claims to make agents safe from self-corruption.

A reflectively stable agent may still pursue dangerous, indifferent, or narrowly self-serving goals. This is not a defect of the framework. It is a deliberate layer boundary. Integrity is a prerequisite for ethics, not a substitute for it.

Questions of value, harm, and inter-agent obligations are deferred by design. Without a stable agent, those questions have no coherent subject. With one, they finally become well-posed.

Where this goes next

The formal paper, Axionic Alignment I: Reflective Stability and the Sovereign Kernel, is now published as a versioned reference document in the Axio repository.

It is intentionally austere. It is meant to be cited, attacked, extended, or proven impossible.

The next step is Axionic Alignment II, which moves from boundary conditions to construction: verifier architectures, kernel upgrade rules, and how conservative agents can still do useful work.

If Alignment I is a type system, Alignment II is about writing programs that type‑check.

Read the formalism skeptically. Break it if you can. If it fails, alignment probably fails with it.