Anarchy and Order

Why consent, not chaos, defines true anarchy

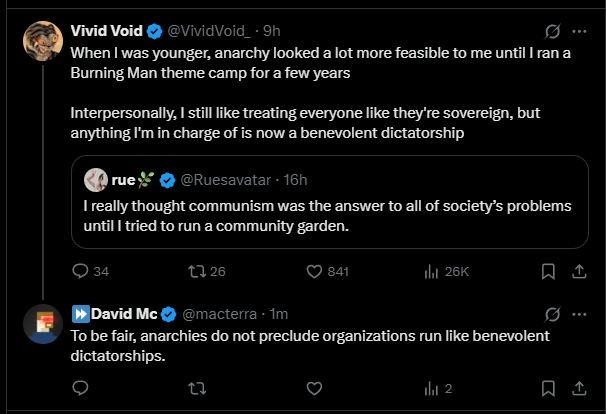

People often dismiss anarchy after trying to run something messy in practice — a theme camp at Burning Man, a community garden, a co-op. The conclusion seems obvious: without a leader, things fall apart, so one must become a benevolent dictator. Case closed. But this reveals a basic misunderstanding of what anarchy actually entails.

Anarchy is not chaos. It is not the absence of organization, nor is it a utopian demand that all human activity be conducted by endless consensus meetings. Anarchy simply means the absence of a coercive monopoly on authority — the state. Within that space, people are free to organize as they wish. And very often, they do choose hierarchies.

A “benevolent dictatorship” within an anarchic framework is not a contradiction. It is an organization where people freely opt in, submit to the leadership for as long as it benefits them, and retain the right of exit. The moment authority becomes coercive — when leaving is punished or forbidden — it ceases to be anarchic. But so long as it remains voluntary, even strong, centralized leadership is fully compatible with anarchism.

This is why anarchies historically contain a mosaic of organizational forms: worker co-ops, trade unions, communes, entrepreneurial ventures, and yes, charismatic leaders who attract followers. What they lack is the monopolistic structure that declares itself sovereign over everyone, regardless of consent.

The lesson isn’t that “anarchy doesn’t work.” The lesson is that human coordination requires different structures in different contexts — sometimes horizontal, sometimes hierarchical, sometimes a hybrid. What matters is whether those structures are entered into and exited from freely.

Anarchy does not mean doing away with leadership. It means leadership must always remain provisional, conditional, and chosen.