Beyond Gender Balance

Accepting Occupational Differences as Natural Consequences of Free Choices

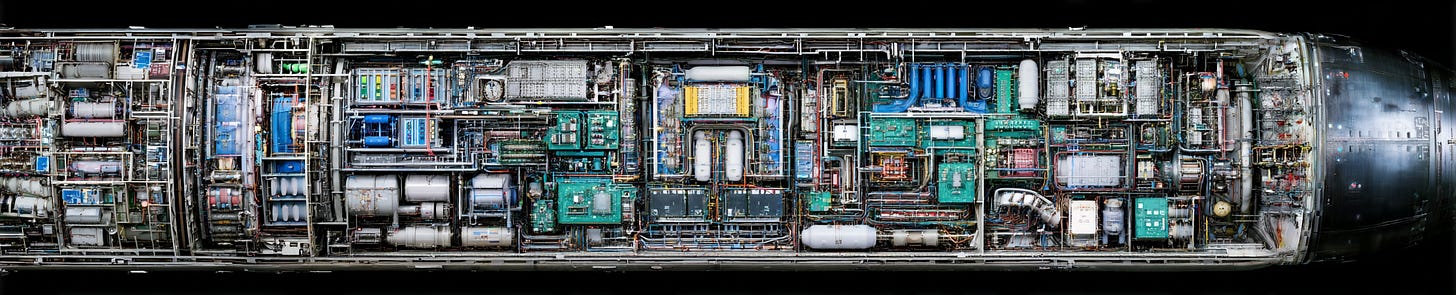

Highly sophisticated technological artifacts—like iPhones, Starship rockets, or undersea fiber-optic cables—represent staggering human accomplishments. When we trace back the immense chain of labor-hours involved in producing such items—from raw resource extraction, heavy manufacturing, intricate engineering, logistics, to final installation and maintenance—a distinct pattern emerges. The overwhelming majority of this labor is performed by males.

Consider a rough breakdown:

Engineering and Technical Design: Fields such as electrical, mechanical, aerospace, and software engineering remain predominantly male. Companies like Apple and SpaceX report that around 75–80% of their technical workforce is male.

Manufacturing and Heavy Industry: Precision machining, metallurgy, component manufacturing, and assembly operations are still overwhelmingly staffed by men, often exceeding 90%, particularly in sectors like aerospace, heavy machinery, and infrastructure.

Raw Materials and Resource Extraction: Mining, refining, and extraction—crucial for rare-earth metals, lithium, cobalt, copper, and aluminum—are heavily male-dominated fields, routinely over 90% male.

Logistics and Infrastructure: Transportation (trucking, shipping, air freight), port handling, and infrastructure construction are overwhelmingly male occupations (80–95%).

Installation and Maintenance: Construction, installation of physical infrastructure such as submarine cables, rocket launch pads, data centers, and telecom towers involve overwhelmingly male crews, typically well above 90%.

There are, of course, exceptions. Certain assembly-line manufacturing roles, particularly electronics assembly in factories across Asia, do involve substantial female participation (around 40–70%). Roles in testing, quality assurance, customer-facing sales, and support often have balanced or female-majority participation. But when viewed comprehensively across global supply chains, these exceptions represent a relatively minor portion of total labor-hours.

Thus, a reasonable estimate is that around 80–90% of the total labor-hours invested across the full lifecycle of sophisticated technological artifacts are performed by males. For extremely heavy-industry-dependent products, such as rockets or deep-sea infrastructure, this figure approaches or exceeds 95%.

Some may instinctively view this gender imbalance as problematic. However, it is not inherently so. Occupational gender disparities are largely reflections of aggregate differences in preferences, interests, physical capabilities, incentives, and voluntary life choices.

Medicine, education, psychology, veterinary care, and nursing, conversely, are predominantly female because women choose these fields at significantly higher rates. Similar voluntary sorting occurs in fields like engineering, construction, and aerospace, with predominantly male participation. These differences, absent coercion or explicit discrimination, reflect free choices rather than systemic injustice.

Still, acknowledging reality means recognizing that entering fields dominated by the opposite sex is typically more challenging. Individuals choosing minority-sex career paths often face additional friction, including:

Social friction: Isolation, fewer shared interests, implicit biases, and stereotypes.

Cultural signaling: Occupational stereotypes influencing educational and career choices.

Mentorship disadvantages: Limited access to mentors and networks dominated by the majority sex.

Workplace norms: Environments and cultures subtly tailored to the majority sex, indirectly raising barriers.

Recognizing these barriers does not imply systemic injustice or call for coercive corrective action, such as quotas or forced equity initiatives. Rather, the optimal approach involves voluntary, non-coercive efforts:

Highlighting role models and success stories from minority-sex participants.

Ensuring unbiased competence assessment and promotion practices.

Encouraging inclusive mentorship cultures without forcibly engineering outcomes.

The goal should never be enforced equality of outcomes or even strict equality of opportunity, as genuine equality of opportunity inherently demands coercive redistribution of prior outcomes, contradicting fundamental principles against coercion. Occupational disparities become unjust only when individuals are coercively prevented from choosing freely based on their interests and abilities.

In short, the gender imbalances observed across sophisticated technological supply chains—and similarly in fields dominated by women—are not intrinsically problematic. They merely reflect aggregate choices, preferences, and realities. Our responsibility is to remove unjust barriers and friction where possible, promoting free choice and individual agency rather than artificially engineering demographic outcomes.