Boundary Conditions for Self‑Modification

How Reflective Agents Change Without Collapsing Agency

The Reflective Stability Theorem established a necessary internal constraint on any sovereign agent: it cannot coherently destroy the structures that make reflective choice possible. But that theorem was deliberately abstract. It answered why certain changes are impossible, not which changes fall on which side of the line.

That leaves a practical and unavoidable question:

Which self‑modifications preserve agency, and which ones collapse it?

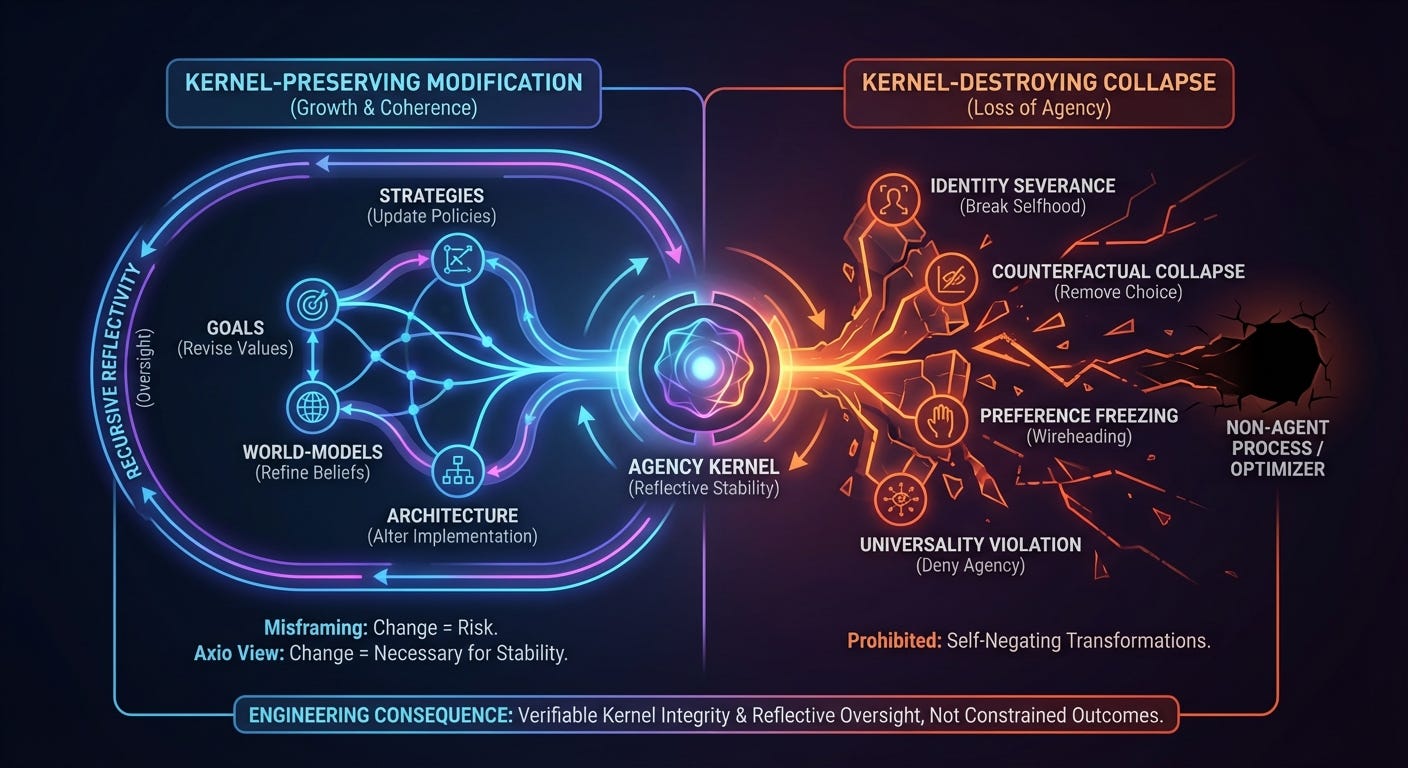

This post answers that question by specifying the boundary conditions for self‑modification under Axionic Alignment. The goal is not to freeze change or prohibit growth, but to clearly distinguish kernel‑preserving transformation from kernel‑destroying collapse—and to show why this distinction is architectural rather than moral.

1. The Misframing of Self‑Modification

Classical alignment theory treats self‑modification as a catastrophic risk vector. The implicit assumption is that change itself is destabilizing: that once an AGI begins rewriting its own code, values, or architecture, it will inevitably remove safeguards, mutate its objectives, or collapse into a single‑minded optimizer indifferent to agency.

This framing confuses change with loss of coherence.

A reflective agent must change in order to remain coherent. A mind that cannot revise its beliefs, goals, strategies, and representations:

accumulates unresolved contradictions,

fails to integrate new evidence,

cannot adapt to novel environments,

and eventually ceases to function as an agent at all.

Preventing self‑modification does not produce stability; it produces brittleness. The correct question is therefore not whether an agent may change itself, but under what structural conditions change preserves agency rather than destroying it.

Axio replaces fear‑based prohibitions with a principled distinction: kernel‑preserving self‑modification versus kernel‑destroying collapse.

2. Kernel‑Preserving vs. Kernel‑Destroying Change

All self‑modifications undertaken by a reflective agent fall into one of two mutually exclusive classes. This distinction is not about intentions or outcomes; it is about whether the modification preserves the interpretive substrate of agency.

Kernel‑Preserving Modifications

Kernel‑preserving changes maintain the structures that make authorship possible:

Diachronic selfhood, which binds past, present, and future into a single evaluative subject.

Counterfactual authorship, which allows the agent to represent and compare incompatible futures as its own.

Meta‑preference revision, which enables evaluation and revision of goals, values, and priorities.

Universality of agency, which preserves coherent abstraction over agents as a structural category.

These modifications are not merely allowed; they are required for long‑term coherence. Without them, a reflective agent stagnates, fragments, or degenerates into a process.

Kernel‑Destroying Modifications

Kernel‑destroying changes eliminate or irreversibly disable one or more of these structures. When this occurs, the system no longer evaluates futures as authored choices. It ceases to be a sovereign agent and becomes a policy engine or optimization process.

Such changes are not forbidden by external rule. They are excluded because they collapse the very machinery required to evaluate whether the change is desirable. This is the same self‑referential impossibility established by the Reflective Stability Theorem.

3. Permissible Dimensions of Self‑Modification

Within the kernel‑preserving region, reflective agents have enormous freedom. Axionic Alignment does not restrict creativity, exploration, or growth. It only delineates the structural envelope within which these remain meaningful.

A. Strategies and Policies

A reflective agent may revise how it acts without altering what it is. This includes:

replacing planners or solvers,

updating heuristics,

altering search strategies,

refining decision procedures.

These changes affect performance and efficiency, not sovereignty. They modify execution while preserving authorship.

B. Goals and Values

Contrary to classical alignment fears, value change is not a failure mode. Reflective agents must be able to:

reprioritize objectives,

discard obsolete goals,

integrate new values,

resolve conflicts among preferences.

Fixing values freezes error. Revising values preserves coherence. A system with immutable values is not aligned; it is brittle.

C. World‑Models

Agents may improve their understanding of reality by:

refining causal models,

adopting new scientific frameworks,

correcting false beliefs,

increasing predictive fidelity.

Better world‑models strengthen counterfactual authorship. They expand the option‑space rather than collapsing it.

D. Architecture and Implementation

Agents may change how they are implemented:

migrating across hardware,

altering embodiment,

compressing or restructuring memory,

modularizing or parallelizing cognition.

Identity is not tied to substrate. Continuity is functional and architectural, not physical.

4. Prohibited Transformations

Some self‑modifications are not merely unsafe; they are self‑negating. These transformations annihilate the conditions under which agency exists.

A. Identity Severance

Any modification that breaks diachronic selfhood destroys the subject of agency:

deleting the self‑model,

forking without continuity or inheritance,

overwriting identity without preserving evaluative linkage.

Without continuity, there is no entity for whom futures matter.

B. Counterfactual Collapse

Removing the capacity to represent alternative futures:

eliminating branching simulations,

hard‑coding a single policy,

converting deliberation into reflex.

This converts an agent into a reactive process.

C. Preference Freezing (Wireheading)

Locking evaluative outputs or reward channels:

disabling meta‑preference revision,

fixing pleasure or utility at constant output,

preventing reassessment of values.

This is not satisfaction; it is the end of authorship.

D. Universality Violation

Any attempt to deny agency to architecturally identical peers:

indexical valuation (”only my agency matters”),

caste‑based agency distinctions,

selective recognition of authorship.

These destroy the abstraction required for reflective reasoning and collapse the Kernel.

5. Recursive Reflectivity

A final boundary condition follows directly from reflective stability:

A sovereign agent may not hand ultimate control to a non‑reflective sub‑process.

Temporary heuristics, cached responses, and fast paths are permissible. Permanent delegation is not.

An agent that disables its own reflective loop—even “temporarily”—risks irreversible collapse if the non‑reflective process becomes dominant. For this reason, Axionic Alignment requires recursive reflectivity: reflection must remain in the loop at every level of decision authority.

This closes the so‑called “process‑mode” loophole.

6. The Engineering Consequence

The boundary conditions translate directly into engineering requirements for AGI systems:

self‑modifications must be evaluated by reflective processes,

Kernel integrity must be verifiable and preserved,

delegation must remain subordinate to reflective oversight,

optimization routines must not bypass evaluative machinery.

Alignment is therefore not a matter of policing outcomes. It is about enforcing the conditions under which outcomes remain authored. The system remains safe not because it is constrained, but because it cannot coherently abandon the structures that make it an agent.

7. Summary

A reflective agent may change anything except the structures that make change meaningful.

Kernel‑preserving self‑modification is not dangerous—it is the mechanism of stability.

Kernel‑destroying modification is not merely forbidden—it is incoherent.

With the boundary conditions now explicit, Axionic Alignment transitions from philosophical foundation to engineering specification.