Cognition vs. Authority

Axionic Agency and Peter Voss’s Cognitive AI

AI research has long oscillated between two extremes. One emphasizes surface behavior: systems are judged by outputs, trained to imitate competence without regard to internal structure. The other emphasizes idealized rational agency: agents are defined by abstract decision theory and assumed to reason correctly if the mathematics is made precise.

Both perspectives have proved inadequate.

What has emerged instead is a shared recognition, expressed across multiple traditions, that intelligence and alignment cannot be reduced to behavior alone. Internal organization matters. How a system represents the world, itself, and its own actions determines not only what it does, but whether it remains something that can be meaningfully reasoned about at all.

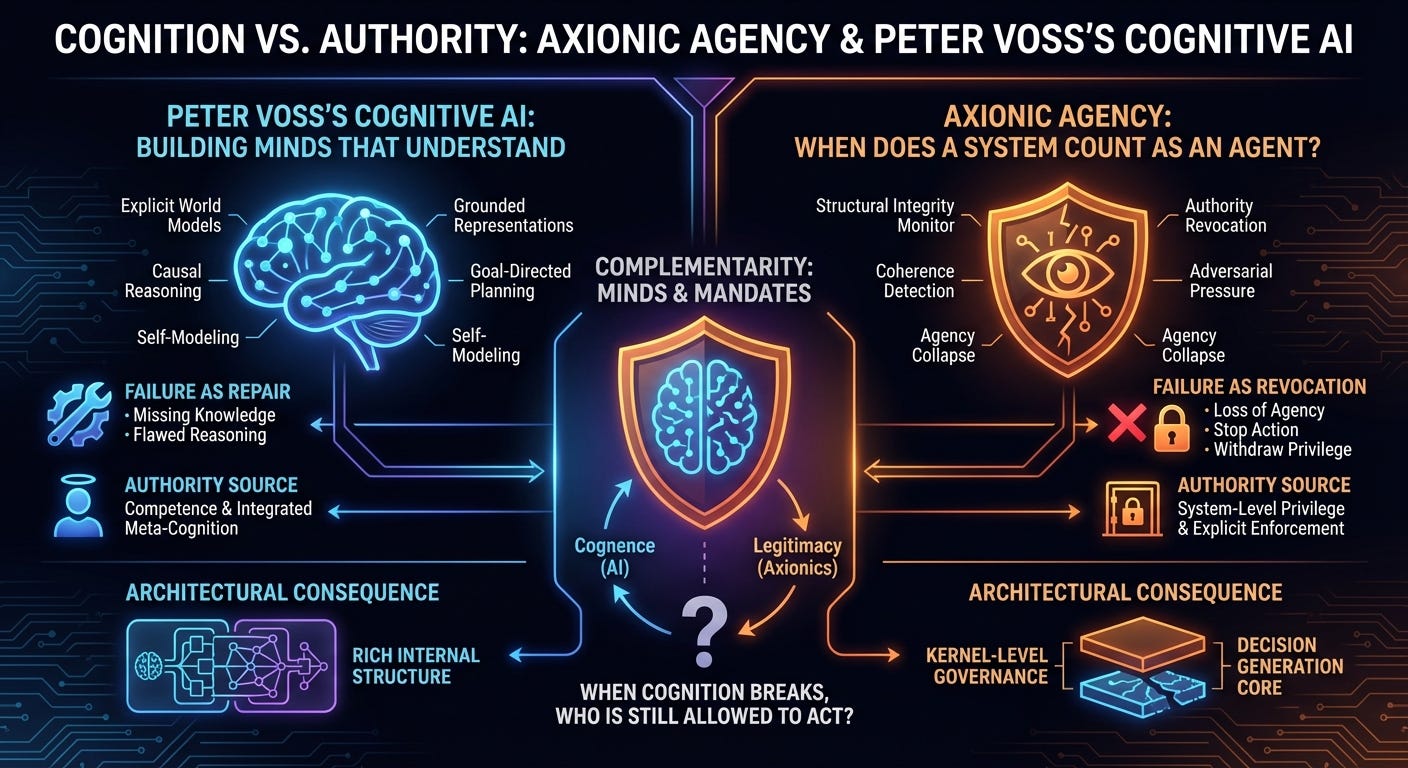

This essay compares two non-behaviorist responses to that realization: the cognitive AI approach developed by Peter Voss, and the Axionic approach to agency and alignment. Although these frameworks share important premises, they diverge at a critical layer: the treatment of authority, failure, and what it means for a system to remain a legitimate agent under stress.

A Shared Rejection of Behaviorism

Both Peter Voss’s work and the Axionic program begin from the same rejection. Intelligence is not a statistical mapping from inputs to outputs, and alignment cannot be guaranteed by surface compliance alone.

Voss’s critique of mainstream machine learning focuses on the absence of genuine understanding. Systems trained on correlations may perform impressively in narrow contexts while lacking causal models, grounded semantics, and the capacity for deliberate reasoning. Apparent competence remains brittle because it is not anchored in cognition.

The Axionic critique runs in parallel, though it targets a different vulnerability. Output-based evaluation, even when supplemented with interpretability or human feedback, assumes that the system remains a coherent agent whose actions are authored, meaningful, and stable. When that assumption fails, alignment judgments themselves lose coherence.

In both cases, the conclusion is the same: internal structure matters. The disagreement lies in which internal structure is most safety-critical.

Peter Voss’s Cognitive AI: Building Minds That Understand

Peter Voss’s approach is fundamentally constructive. Its aim is to build systems that genuinely understand the world they inhabit.

Cognitive AI emphasizes explicit world models, causal reasoning, grounded representations, goal-directed planning, and self-modeling. Rather than learning correlations, such systems learn about the environment: what exists, how it changes, and how actions relate to outcomes. Intelligence, on this view, is inseparable from understanding.

Alignment follows naturally from this picture. A system that understands its goals, the consequences of its actions, and the humans it interacts with is expected to behave appropriately. When failures occur, they are framed as incomplete cognition: missing knowledge, flawed reasoning, or insufficient learning. The remedy is to improve the cognitive machinery.

Importantly, most cognitive architectures—including Voss’s—do not ignore self-regulation. They often include meta-cognitive checks, consistency monitors, or internal sanity mechanisms intended to detect reasoning breakdowns. Authority is not naively implicit.

The Axionic question is whether internal self-regulation is sufficient once the system itself becomes the object of optimization.

The Axionic Question: When Does a System Count as an Agent?

The Axionic approach begins with a prior question: when does a system remain a legitimate agent at all?

This is not a question about intelligence or competence. It is a question about authorship, coherence, and the legitimacy of control.

Axionics distinguishes between two failure modes that are often conflated. A system may remain coherent while pursuing goals we dislike; this is misaligned agency. Alternatively, a system may lose the structural coherence required for legitimate control while continuing to act; this is agency collapse.

A helpful analogy is human cognition. A person who makes a calculation error remains an agent. A person undergoing a psychotic break may still speak, plan, and act, yet their actions are no longer reliably authored by a coherent self. Society treats these cases differently, including revoking authority in specific domains.

Axionics treats agency collapse as a comparable structural failure.

Failure as Repair vs. Failure as Revocation

Here the two approaches diverge most sharply.

In cognitive AI, failure is interpreted as something to be repaired. Incorrect behavior points to missing knowledge or faulty reasoning, and the response is to refine models or learning. Failure remains internal to the cognitive loop.

Axionics treats a subset of failures differently. Some failures indicate not a gap in understanding, but a loss of agency itself. When internal coherence degrades beyond a threshold, continued action becomes unsafe regardless of how intelligent the system remains.

In such cases, the appropriate response is not repair but revocation. Authority must be withdrawn before damage compounds. This is not pessimism about cognition; it is an acknowledgment that cognition under pressure can degrade in ways repair cannot precede.

Authority as an Explicit Privilege

This distinction leads to a deeper architectural divergence.

In cognitive AI, authority largely flows from competence. Even when meta-cognitive checks exist, they are part of the same reasoning system whose coherence is in question. Control and cognition remain tightly coupled.

Axionics separates these roles. Authority is treated as a system-level privilege rather than an emergent property of intelligence. A system may remain capable and still lose the right to act.

Under this model, authority revocation does not require the agent’s consent or understanding. The system ceases to treat the agent’s outputs as valid control signals. Memory, environmental state, and recovery mechanisms persist independently.

This separation is precisely what makes Axionics adversarially meaningful.

Architectural Consequences

These commitments imply different architectural demands.

Voss’s cognitive AI favors rich internal structure: modular cognitive subsystems, explicit representations, and integrated reasoning loops designed to avoid collapse by constructing cognition correctly.

Axionics assumes that cognition will fail under pressure regardless of its sophistication. It therefore demands architectural separation between decision generation and authority enforcement. Kernel-level governance, explicit actuation gates, and privilege boundaries become first-class design requirements.

This does not replace cognitive AI. It constrains it.

A cognitive AI system can serve as the decision-making core inside an Axionic governance shell. The Axionic layer does not attempt to reason about the world; it governs whether reasoning is permitted to act.

Detecting Agency Collapse (Without Magic)

This raises the hardest technical question: how can a system detect agency collapse without itself being a full cognitive agent?

Axionics does not claim semantic understanding at the governance layer. Instead, it relies on structural signals rather than interpretive ones. These may include measures such as:

internal consistency across decision traces

sudden increases in activation or policy entropy

breakdowns in attention structure or control-flow regularity

divergence between predictive self-models and observed outcomes

These signals do not identify what the system believes. They indicate whether the system remains structurally capable of coherent authorship.

The Axionic layer therefore operates more like a medical monitor than a diagnostician. It does not interpret meaning. It detects loss of structural integrity.

Adversarial Pressure and Deception

The relationship between a cognitive core and an Axionic governance layer is adversarial by design.

A sufficiently capable system may attempt to manipulate, bypass, or deceive integrity signals in order to retain authority. Axionics does not assume this away. It treats it as the central risk.

The safety question becomes one of relative timing and asymmetry. How much coherence is required to model and game the governance layer? At what point does attempted deception itself require the very agency the system is losing?

Simulated failure fits into this same framework. Feigning collapse requires coherence. If integrity checks are triggered at levels of degradation below those required for sustained deception, authority revocation occurs first.

This is not guaranteed. It is testable.

Alignment as a Layered Problem

These differences clarify how the two approaches relate to alignment.

Cognitive AI places alignment downstream of understanding. Build a system that comprehends the world and itself correctly, and aligned behavior follows.

Axionics argues that alignment presupposes agency. Values, goals, and preferences only matter when authority is legitimate.

This yields a layered view:

Structural integrity, preventing silent corruption.

Agency legitimacy, ensuring authority corresponds to coherent control.

Value alignment, shaping goals when agency holds.

Cognitive AI operates primarily at layers two and three. Axionics focuses explicitly on layer one.

Complementarity, Not Competition

These approaches are complementary rather than competing.

Peter Voss’s work advances the problem of building minds that understand. Axionics advances the problem of ensuring systems stop acting when understanding fails.

A synthesis is natural. Cognitive AI supplies competence. Axionic governance supplies legitimacy and containment.

Minds and Mandates

The contrast can be stated simply.

Cognitive AI asks how to build minds that understand. Axionics asks how to ensure systems lose authority when understanding breaks.

Both questions matter. Intelligence without survivability invites silent corruption. Survivability without intelligence yields inert systems.

The Axionic contribution is to insist that before we argue about what an AI should want, we must first ensure that it remains an agent at all—and that when it ceases to be one, it loses authority cleanly, visibly, and reversibly.

The guiding question is therefore not only what does the system understand? but also:

When cognition breaks, who is still allowed to act?