Conditional Divinity

God exists only to the degree agents recognize what’s best

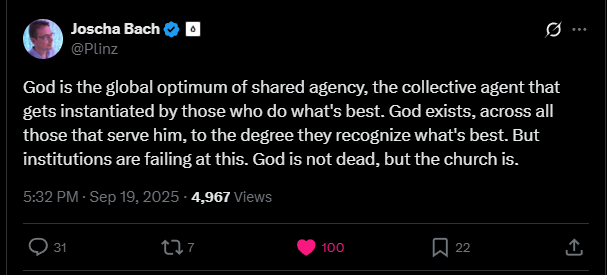

Joscha Bach reframes God not as a supernatural being, but as an emergent attractor in the space of agency. He defines God as the global optimum of shared agency: the highest point of alignment where individuals act in ways that converge toward what is best. This is not a deity outside the world but a process instantiated within it.

Key Claims

God as a Collective Agent

God is instantiated when individuals pursue what is best. He is distributed across all agents, existing to the extent that they align their actions with truth, reason, and goodness.Existence by Recognition

God’s “existence” is partial and proportional. The more individuals recognize and enact what is best, the more real this God becomes.Institutional Failure

Traditional institutions—the church in particular—once served as vessels for coordinating shared agency. Bach argues that they no longer fulfill this role. The ideal persists, but its institutional embodiment has decayed.Provocative Conclusion

“God is not dead, but the church is.” The transcendent attractor still exists; the human vessel has failed.

Evaluation

Philosophical Strengths

Naturalization of God: By defining God as an emergent attractor of agency, Bach avoids supernaturalism while preserving the aspirational and motivational force of the divine.

Continuity with Tradition: This view echoes Spinoza’s Deus sive Natura and Teilhard de Chardin’s Omega Point, but articulated in computational and optimization terms.

Sharp Institutional Critique: The contrast between living ideal and dying institutions resonates strongly with contemporary religious decline.

Philosophical Weaknesses

Ambiguity of “What’s Best”: The definition of the optimum is underspecified. Utilitarian happiness? Agency preservation? Truth-seeking? Without a criterion, the attractor risks collapsing into mere personal opinion.

Epistemic Optimism: The framework assumes humans can reliably recognize what is best. In reality, biases, tribal incentives, and deep moral disagreement make this recognition contested and fragile.

Suppression of Divergence: Collective agency can become oppressive. Sometimes it is the dissenting minority, not the collective, that points closer to truth. A “global optimum” risks erasing local optima that matter for innovation and freedom.

Relation to Broader Thought

Nietzsche Inversion: Nietzsche declared God dead because metaphysical institutions collapsed. Bach argues the inverse: God persists as an emergent ideal, but the church has failed as a vessel.

Game Theory Lens: God here is the coordination equilibrium of “do what’s best.” The challenge is not defining the attractor, but building mechanisms—trust, signaling, enforcement—to approach it.

Connection to QBU and Conditionalism: In the Quantum Branching Universe framework, “God” as global optimum parallels the Measure of branches that maximize agency. Conditionalism clarifies the hidden assumptions behind “what’s best.” Bach’s definition thus dovetails with a rationalist metaphysics of choice and agency.

God Without Priests

Bach’s definition is elegant but incomplete. It succeeds in reinterpreting God as an emergent attractor of agency but glosses over the hard problem: how we discover, justify, and coordinate around “what’s best.” Without rigorous value-discovery mechanisms, this God risks becoming a rhetorical flourish for personal conviction. Institutions may have failed, but they failed at precisely the task Bach’s God requires—resolving pluralism into coordinated agency.

Perhaps the error is thinking God requires a church at all. If God is instantiated wherever agency aligns with the best, then He lives in distributed form—in code, in markets, in small communities, in fleeting acts of truth. The priests are gone, but the pattern persists.