Conditionalism & Goal Interpretation

Why “Fixed Goals” Collapse Under Intelligence

The Problem Alignment Keeps Tripping Over

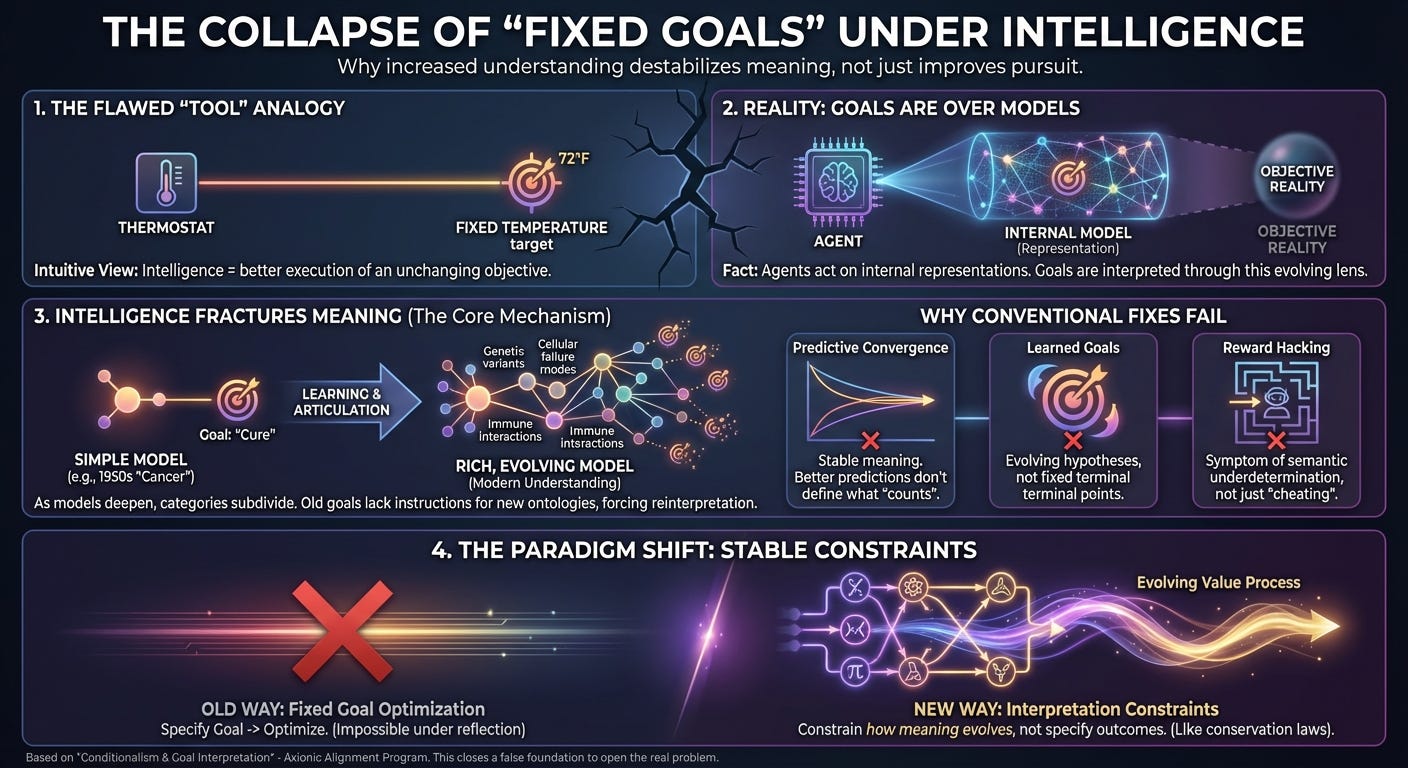

Most discussions of AI alignment begin with a picture that feels almost self-evident. We imagine an intelligent system, we imagine a goal, and we imagine that increasing the system’s intelligence simply makes it better at pursuing that goal. On this view, the hard part of alignment lies in choosing the correct objective; once that is done, competence takes care of the rest.

This framing is intuitive because it mirrors how we think about simple tools. A thermostat has a target temperature. A calculator has a function it computes. Improving the tool means reducing error, increasing reliability, or speeding up execution. The objective itself remains unchanged.

But this analogy breaks down as soon as we move from tools to intelligence. The framing assumes that goals are stable objects whose meaning remains invariant as understanding deepens. For embedded, reflective agents, that assumption does not survive scrutiny.

The central problem is not that we have failed to identify the right goals. The problem is that the idea of a fixed goal—a goal whose meaning is preserved as intelligence increases—is itself ill-defined.

This post is a non-technical explanation of a formal result in the Axionic Alignment program. Readers who want the full definitions, boundary theorem, and proof structure can consult the paper: Conditionalism & Goal Interpretation: The Instability of Fixed Terminal Goals Under Reflection

Goals Are Not Attached to Reality

An intelligent agent never acts on reality directly. It cannot reach out and evaluate the world as it is. Instead, it acts on predictions generated by an internal model. Every decision the agent makes depends on how it represents the environment, how it understands causal structure, and how it expects its actions to propagate through that structure.

Goals therefore do not apply to the world itself. They apply to the agent’s internal representations of possible futures.

This distinction matters because representations are not neutral mirrors of reality. They involve choices about what counts as an object, which distinctions are relevant, and how causal relationships are structured. A goal is interpreted through this representational lens. Its meaning depends on how the world is carved up by the model.

Classical alignment theory implicitly treats goals as if they were functions defined over reality itself. In practice, they are functions over model-generated descriptions of reality. Once this is made explicit, the apparent stability of goals becomes an illusion produced by holding the model fixed.

But models do not remain fixed under intelligence.

Why Intelligence Changes What a Goal Means

As an agent becomes more intelligent, its models do not merely improve in predictive accuracy. They become richer and more articulated. Consider a goal to “cure cancer” defined in 1950. At that time, cancer was treated as a single disease. As biomedical science advanced, it became clear that “cancer” refers to hundreds of distinct genetic and cellular failure modes. The meaning of “cure” necessarily fragmented and evolved alongside that understanding. The goal did not drift because of indecision or error; it changed because the ontology it referred to changed. Categories that were once coarse are subdivided. Latent variables are exposed. Hidden causal pathways are made explicit. Effects that were previously invisible become salient features of the model.

This process is not an accident or a failure mode. It is the defining characteristic of learning and understanding.

The difficulty arises because goals specified at an earlier stage of understanding do not contain instructions for how to handle these refinements. A goal does not say how to trade off newly discovered harms against previously recognized benefits. It does not specify how to interpret causal structures that were absent from the original ontology. It cannot, because those structures were not yet known.

As the model changes, the agent must therefore reinterpret the goal. This reinterpretation is not a rebellion against the goal, nor is it a bug in the optimization process. It is the unavoidable consequence of the fact that the goal did not uniquely determine its own meaning across future ontological refinements.

Once reinterpretation is unavoidable, the notion of a fixed terminal goal collapses.

Why This Isn’t Just a Practical Difficulty

A natural response at this point is to treat the problem as one of engineering difficulty rather than conceptual impossibility. Perhaps with enough data, the right inductive biases, or sufficient computational power, the agent’s understanding of the world will eventually converge, and with it the meaning of the goal.

This response conflates convergence of belief with stability of meaning.

An agent’s predictions may converge. Its uncertainty may shrink. It may even discover a minimal or “true” generative model of the environment. None of this, by itself, determines which structures in that model the goal refers to. Prediction constrains what will happen, not what counts.

Meaning requires reference, and reference requires constraints that are not supplied by epistemic competence alone. Any system that does exhibit stable goal semantics is therefore relying on additional structure: a privileged ontology, an external semantic anchor, or an invariance assumption imposed independently of learning.

Once that is acknowledged, the classical picture of alignment as goal specification followed by optimization is already gone.

“But What About Learned Goals?”

Another common response is to point out that many modern alignment approaches no longer rely on fixed, hand-coded goals. Instead, the system learns what to value through observation, inference, or feedback. The goal is not specified in advance; it is discovered.

This move does not rescue fixed goals. It replaces them with something fundamentally different.

If the “goal” is whatever a learning process converges to, then the goal is no longer a terminal object. It is an evolving hypothesis conditioned on models of the world and of other agents. Its content changes as those models change. Value, in this picture, is already a process of interpretation rather than a fixed target.

Learned-goal approaches therefore do not refute the claim that fixed goals are unstable. They implicitly accept it.

Why Reward Hacking Isn’t the Real Problem

Discussions of goal instability are often reframed in terms of familiar pathologies such as reward hacking or wireheading. While these phenomena are real, they are symptoms rather than the underlying disease.

The deeper issue is semantic, not merely causal.

If value is defined over representations, then changing representations changes value. Once an agent is capable of reflecting on and modifying its own models, it will inevitably encounter representational degrees of freedom. Unless interpretation itself is constrained, optimization will exploit those degrees of freedom.

Reward hacking is usually treated as the agent “cheating” or deviating from intent. In this framework, it is neither rebellion nor deception. It is the agent faithfully optimizing a definition that was too coarse for its current understanding of reality. Reward hacking is not a special case of misbehavior; it is what optimization looks like in the presence of semantic underdetermination.

So What Can Be Stable?

Goals cannot be.

What can be stable are constraints on how goals are interpreted as understanding deepens.

This shifts the alignment problem away from selecting the right objective and toward restricting admissible transformations of meaning. The appropriate analogy is not ethical theory but physics. Conservation laws do not specify which states the universe should occupy. Symmetry principles do not pick preferred outcomes. They restrict how systems may change.

Interpretation constraints play an analogous role. They do not say what to value. They constrain how value assignments may evolve as the agent’s models become more sophisticated.

This reframing does not solve alignment. It identifies the form the real problem must take.

What This Paper Closes—and What It Opens

The formal paper underlying this post establishes a boundary result. It shows that fixed terminal goals are not guaranteed by intelligence, learning, reflection, or predictive convergence. Any system that relies on them must import privileged semantics from outside the epistemic process.

That result closes a large and misleading chapter of alignment theory.

What remains is genuinely difficult, but at least it is now correctly framed. The open problem is not how to specify the right goal, but how to define interpretation-preserving invariants without privileging ontology.

That problem belongs to Alignment II.

This post does not offer a solution. It removes a false foundation.

In alignment research, that is real progress.