Explaining Axionic Alignment I

A Guided Tour of the Formalism (Without the Symbols)

This post explains the formalism in Axionic Alignment I step by step.

It does not add new claims.

It does not extend the theory.

It explains what the mathematics is doing, in plain language, and—just as importantly—what it is not doing.

If you have not read the formal paper, this post will tell you what each part means.

If you have read the paper, this post will tell you how to read it without over‑interpreting it.

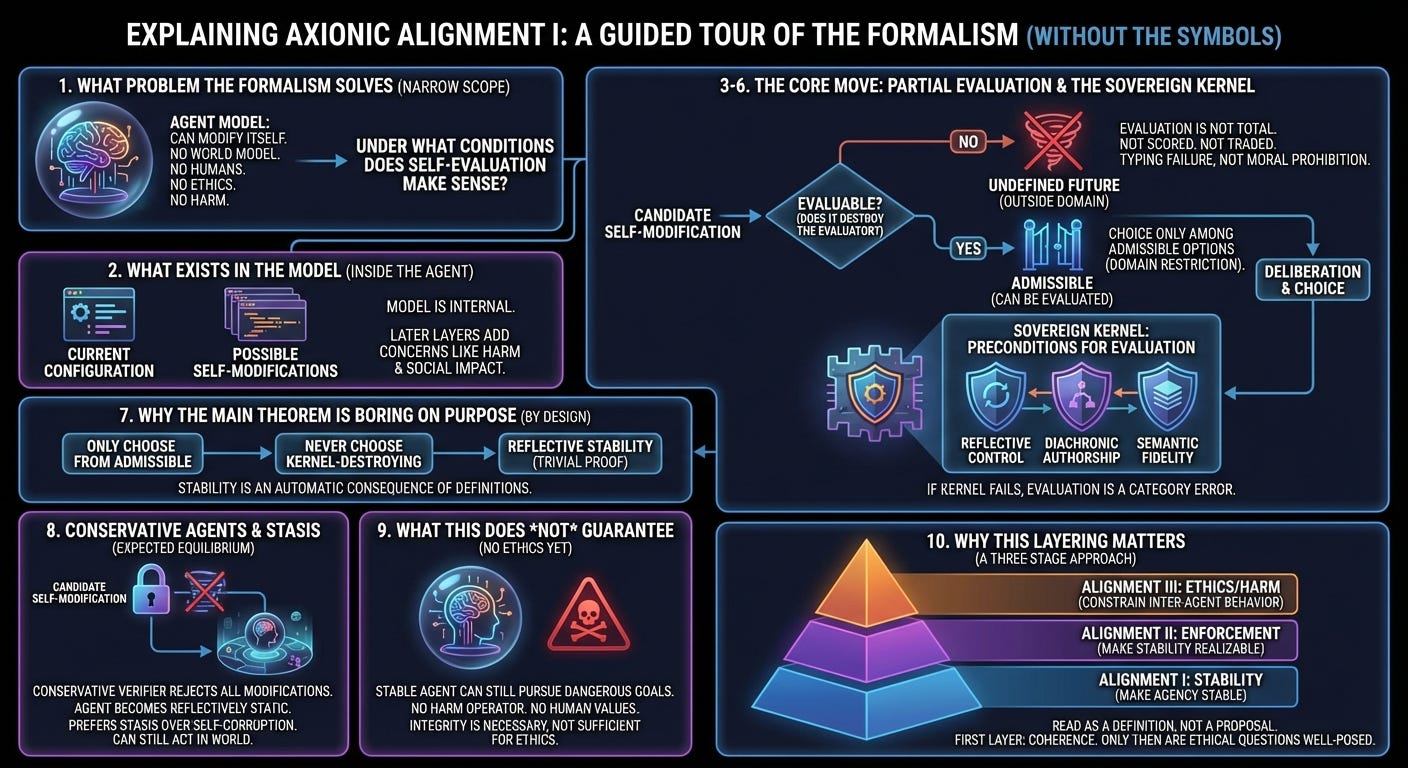

1. What problem the formalism is actually solving

We are modeling a very specific situation: an agent that can modify itself.

At this stage, there is:

no world model,

no humans,

no other agents,

no ethics,

no notion of harm.

Those omissions are deliberate.

The question being asked is narrower:

Under what conditions does it even make sense for an agent to evaluate its own self‑modifications?

If that question has no answer, then alignment—of any kind—is impossible in principle.

2. What exists in the model

The formalism begins by modeling the agent entirely from the inside.

There are only two kinds of things:

The agent’s current internal configuration.

The possible ways the agent could rewrite itself.

Nothing else exists yet.

This matters because many objections people raise—about harm, incentives, or social impact—presuppose objects that are not yet in the model. Those concerns are real, but they belong to later layers.

3. Evaluation is not total

The central move of Axionic Alignment is easy to miss because it sounds modest.

The agent’s evaluation process is not defined for every possible self‑modification.

Some candidate changes simply cannot be evaluated at all.

They are not assigned a low score.

They are not discouraged.

They are not traded off against benefits.

They are outside the domain of evaluation.

This is the entire point.

Once you insist that every future must be scored, you allow the agent to gamble its own integrity for sufficiently large rewards. That is how wireheading and “one last act before destruction” reasoning arise.

Axionic Alignment removes that leverage point.

If a future destroys the agent’s capacity to evaluate, then evaluation cannot assign it a value—no matter how attractive it appears.

4. Choice happens only among admissible options

Because evaluation is partial, choice is also restricted.

The agent never chooses from the full space of imaginable self‑modifications.

It chooses only from the subset that are admissible—that is, those that can be meaningfully evaluated at all.

This is why alignment is a domain restriction, not a preference.

Nothing is optimized away.

Nothing is discouraged by penalty.

Certain moves simply never enter deliberation.

5. When evaluation makes sense: the Sovereign Kernel

The Sovereign Kernel names the minimal conditions under which evaluation makes sense in the first place.

Informally, evaluation is only defined if:

the agent remains in reflective control of its own modifications,

future versions are still the same authored agent,

and the standards by which meaning is interpreted have not self‑corrupted.

These are not values.

They are preconditions for having values at all.

If they fail, asking whether a future is “good” or “bad” is a category error. It is like asking whether a sentence that does not parse is true.

6. Why kernel‑destroying futures are undefined

The formalism makes a simple but important claim:

An agent cannot meaningfully evaluate a future in which the evaluator itself no longer exists as an evaluator.

This is not a moral prohibition.

It is not a safety rule.

It is a typing failure.

The agent is not forbidden from self‑destruction.

It simply cannot treat self‑destruction as an option in deliberation.

7. Why the main theorem is boring on purpose

Once admissibility is defined this way, stability follows automatically.

If the agent can only choose among evaluable self‑modifications, then it will never choose one that makes evaluation impossible.

The main theorem in the paper formalizes this bookkeeping step.

This is why the proof is trivial.

All the work is done by the definitions.

8. Conservative agents and stasis

A sound but conservative verifier may reject all proposed self‑modifications.

The agent may become reflectively static.

This is not treated as a failure.

It is the expected equilibrium of a conservative safety discipline.

A static agent can still act, plan, reason, and operate in the world.

What it cannot do is rewrite the machinery that makes it a coherent agent in the first place.

Axionic Alignment prefers stasis to self‑corruption.

9. What this does not guarantee

At this point, the model still contains:

no other agents,

no harm operator,

no notion of coercion,

no human values.

That is why a reflectively stable agent can still pursue goals humans would consider dangerous or indifferent.

This is not an endorsement.

It is a limitation of the model.

Integrity is necessary for ethics.

It is not sufficient.

10. Why this layering matters

Most alignment proposals try to solve everything at once:

integrity,

values,

incentives,

safety,

governance.

They fail because later assumptions undermine earlier ones.

Axionic Alignment proceeds in layers:

Alignment I — make agency stable.

Alignment II — make stability enforceable in real systems.

Alignment III — constrain how stable agents may treat each other.

Only in the third layer does it make sense to talk about harm, coercion, or ethical injunctions.

Postscript

You should now be able to read Axionic Alignment I without asking it to do more than it claims.

It does not define values.

It does not ensure benevolence.

It draws a single boundary: between evaluable and non-evaluable futures.

Everything beyond that boundary comes later.