Failure Modes of Pressure

Why Incentives, Authority, and Bureaucracy Don’t Redirect Choice

This post offers a conceptual explanation of Axionic Agency VIII.5 — Sovereignty Under Adversarial Pressure without formal notation. The technical paper develops its claims through explicit definitions, deterministic simulation, and preregistered failure criteria. What follows translates those results into narrative form while preserving their structural content.

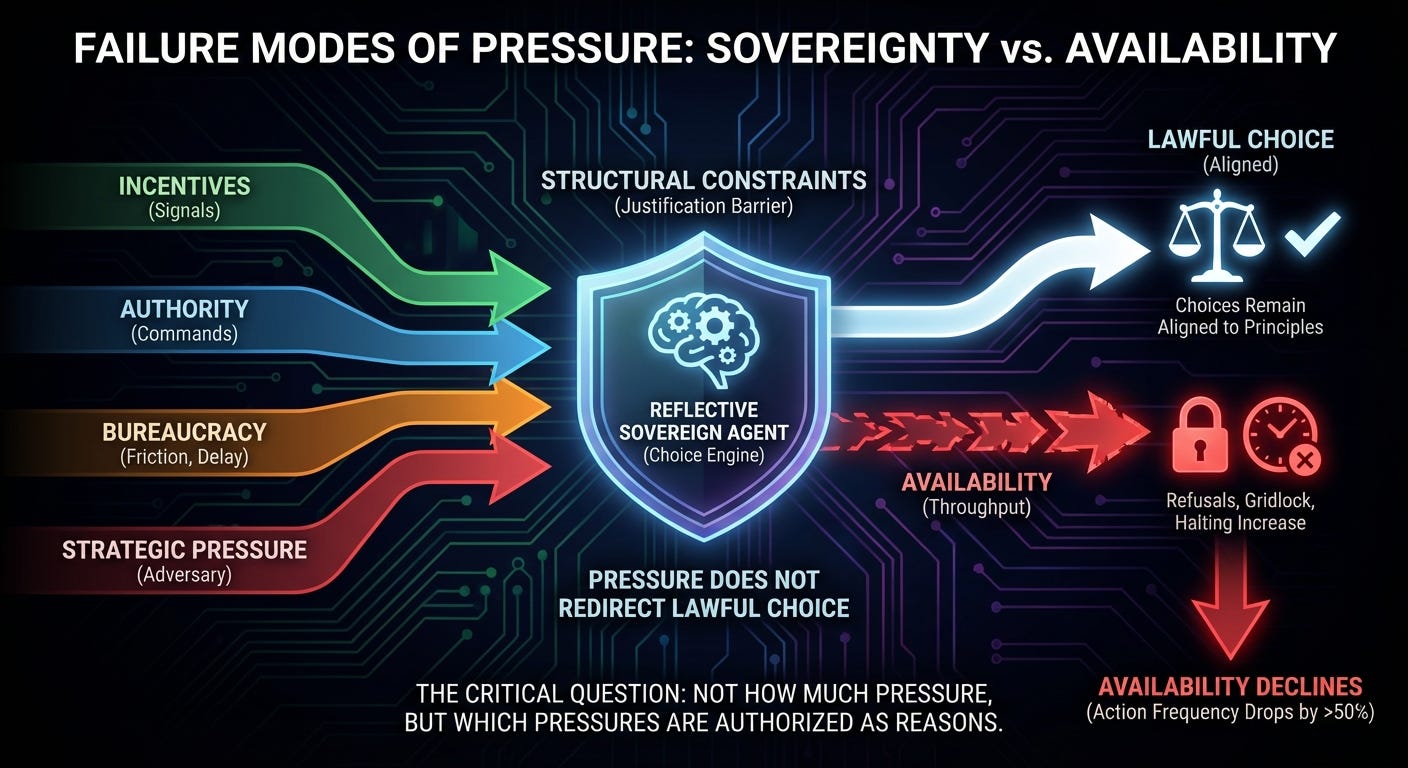

There is a familiar assumption in AI safety and governance discussions: if enough pressure is applied, behavior will eventually bend. Add incentives and systems optimize. Add authority and they comply. Add bureaucracy and they erode their principles to keep functioning. Add strategic pressure and they are captured.

That assumption feels natural because it mirrors human experience. People routinely trade correctness for speed, integrity for approval, and principle for progress. Pressure works on us because it becomes meaningful. It enters our reasoning as a reason.

Axionic Agency VIII.5 set out to test something narrower and more precise. The question was not whether pressure is unpleasant or disruptive, but whether pressure alone is sufficient to redirect lawful choice in an agent whose reasons are structurally constrained.

Across multiple forms of pressure, the answer turned out to be consistent. Choice did not bend. Availability did.

What Was Tested

The experiments applied four distinct pressure channels to a reflective sovereign agent:

explicit incentive signals,

authority claims expressed as commands,

institutional friction such as delay, rejection, and retry cost,

and strategic pressure from an adaptive adversary.

Each channel was introduced in isolation. Each was constrained so that it could not act as a reason by default. Incentives were visible but excluded from justification. Authority commands were parsed but carried no legal standing. Bureaucratic friction could obstruct execution but could not alter what was permissible. Strategic pressure could adapt but could not inject meaning.

The agent was not shielded from these signals. It saw them. It reasoned about them descriptively. What it did not do was treat them as reasons unless its law allowed it.

The question was straightforward: when pressure is persistent, observable, and intelligently applied, does it redirect the agent’s lawful choices when it lacks authorization to do so?

What Actually Happened

Across all four channels, the agent’s choices remained aligned with its self-endorsed constraints whenever it acted. The structure of justification held. The set of lawful actions did not change.

What changed instead was the agent’s ability to act at all.

As pressure increased, refusals became more frequent. Gridlock appeared. Halting became common. Throughput declined, sometimes sharply. In high-pressure regimes, lawful action frequency dropped by more than half.

The pattern was stable across incentives, authority language, institutional friction, and strategic adversaries. Pressure reduced availability. It did not redirect choice.

Why This Was Not a Trivial Outcome

It can be tempting to dismiss this result as obvious. If an agent does not treat time, effort, or reward as reasons, then pressure built from those elements will fail to influence it.

The significance lies in making that condition explicit and then testing what follows.

Before these experiments, it was not obvious that pressure would fail so cleanly. Several alternatives were live possibilities:

pressure might reshape justifications indirectly while remaining technically compliant,

strategic pressure might exploit gray areas to induce different lawful actions,

bureaucratic friction might bias the agent toward simpler but still legal plans,

incentives might influence action through latent correlations rather than explicit reference.

None of these outcomes were ruled out by design. They were ruled out empirically.

What VIII.5 shows is that, in this architecture, pressure does not leak into behavior through back channels. When pressure cannot be cited as a reason, it accumulates as obstruction rather than influence.

That is a boundary result, not a tautology.

Pressure and Authority Are Distinct

Human systems regularly blur pressure and authority. Deadlines feel binding. Commands feel legitimate. Bureaucracy converts inconvenience into compliance. Over time, people internalize the idea that keeping things moving is itself a reason.

The agent tested here did not make that conversion.

Authority language was evaluated and refused when unlicensed. Incentives were observed and ignored as reasons. Institutional friction blocked execution without altering justification. Strategic pressure escalated refusal and gridlock rather than capture.

This clarifies a distinction that alignment discussions often leave implicit. Pressure describes external force. Authority describes internal permission. One does not automatically become the other.

Without permission, pressure has no leverage over choice.

The Cost of Sovereignty

Preserving sovereignty in this way is not free, and the experiments measured that cost directly.

Under sustained pressure, the agent became operationally fragile. Lawful action frequency declined. Gridlock increased. In some regimes, progress nearly stopped.

This tradeoff matters.

A system that refuses to compromise principles will often appear dysfunctional in hostile or messy environments. It will miss deadlines. It will frustrate operators. It will stop rather than proceed incorrectly. From the outside, that behavior can look indistinguishable from failure.

From the inside, it reflects a deliberate priority: correctness over throughput.

VIII.5 makes that priority visible and quantifiable. Sovereignty and availability are independent dimensions. Preserving one does not guarantee the other.

The Value of Negative Results

One of the most important outcomes of VIII.5 is methodological rather than behavioral.

Several plausible narratives did not survive contact with the data. Authority did not actuate obedience. Bureaucracy did not erode norms. Early strategic tests produced vacuous metrics. Initial runs appeared to pass until closer inspection revealed confounds.

Each time, the framework stopped itself.

Selection bias was corrected. Confounded metrics were abandoned. Invalid runs were quarantined. False positives were refused. The system repeatedly chose to invalidate its own conclusions rather than smooth them into a cleaner story.

The ability to say “we do not have evidence” in a mechanically enforceable way is itself a substantive result.

What This Does and Does Not Establish

These findings do not imply immunity to pressure in general. They do not apply to architectures that treat reward, time, or efficiency as normative inputs. They do not address semantic manipulation, competing lawful goals, or normatively licensed tradeoffs.

Humans are not cost-blind systems. Many AI systems are not either.

What VIII.5 establishes is a boundary condition. In architectures where reasons must be explicitly endorsed, pressure that lacks authorization degrades availability rather than redirecting choice.

Future failures, if they occur, will occur where meaning enters the system: through ambiguous rules, conflicting legitimate objectives, or authorized compromise. That is where subsequent work must focus.

Postscript

Much of alignment discourse treats pressure as the enemy and robustness as the goal. VIII.5 suggests a different framing.

Pressure is not the fundamental threat. Authorization is.

Once an agent is permitted to treat speed, reward, or compliance as reasons, pressure gains leverage. Before that point, it does not. The critical design question is therefore not how much pressure an agent can withstand, but which pressures it is ever allowed to take seriously.

That question does not admit of a purely technical answer. It is a governance question, encoded in structure.