Games and Metagames

Seeing the Hidden Structure Behind Every Choice

1. Why Start With Games?

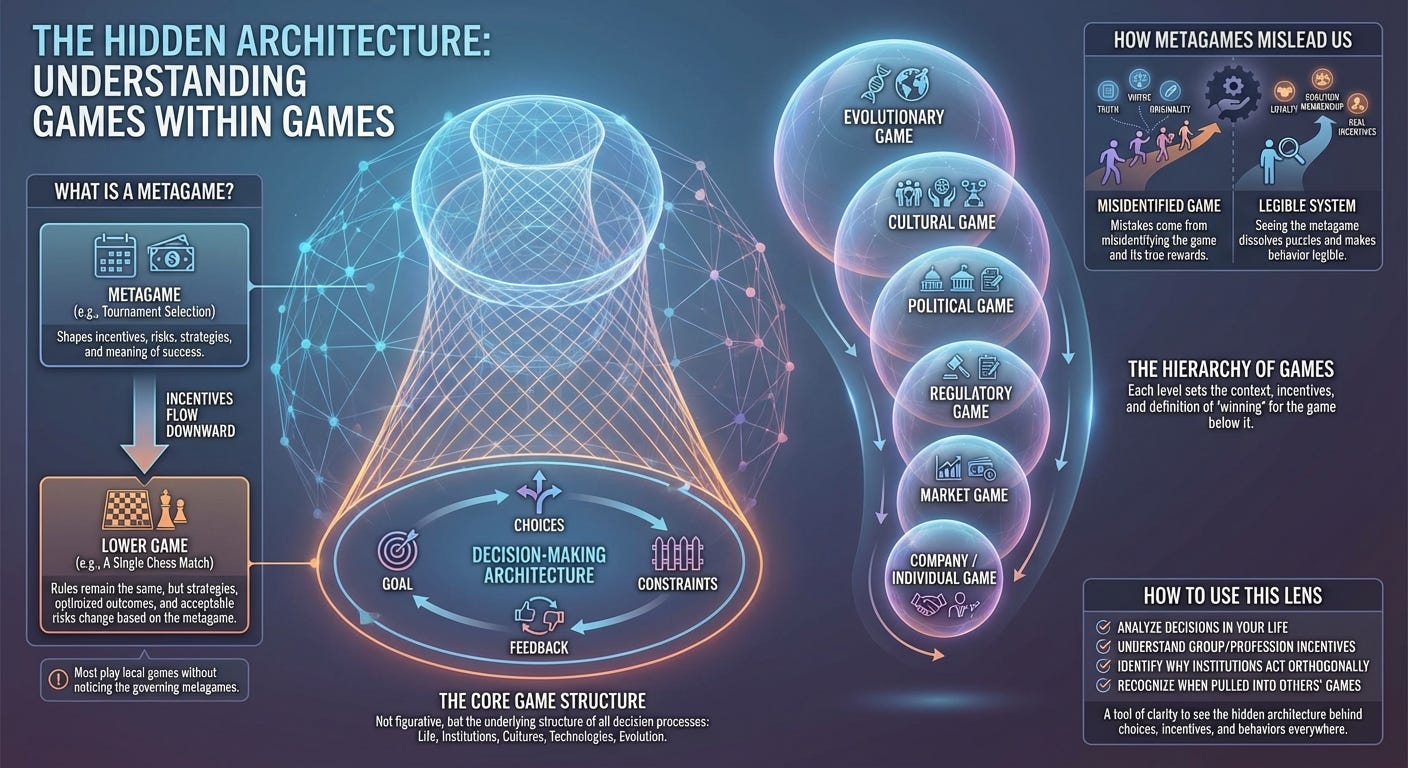

People usually think of games as optional pastimes: chess, soccer, video games, poker. But the concept of a game is deeper than that. Whenever you have:

a goal,

choices among possible actions,

constraints that limit or shape those actions,

and feedback that distinguishes better outcomes from worse ones,

you are in a game.

This is not figurative language; it reflects the underlying architecture shared by all decision‑making processes. Life, institutions, cultures, technologies, and even biological evolution all follow this pattern: agents navigating a landscape of incentives with strategies that succeed or fail.

Recognizing this structure makes agency, strategy, conflict, cooperation, and survival easier to understand.

2. The Hierarchy of Games

Once you see games everywhere, something striking becomes obvious: every game sits inside a larger one.

A company plays a market game, which sits inside a regulatory game, which sits inside a political game, which sits inside a cultural game, which sits inside an evolutionary game.

The same pattern appears in every domain:

individuals inside families,

families inside communities,

communities inside nations,

nations inside global systems.

Each level sets the context for the game below it. What counts as “winning” in a lower game depends on the incentives and constraints of a higher one.

You cannot understand why people behave the way they do unless you see the higher‑level game shaping their choices.

3. What Is a Metagame?

A metagame is the game above the one you are looking at — a game with its own goals, strategies, and rules, distinct from the lower game.

If the game is chess, the metagame is choosing which tournaments to enter — a decision that shapes incentives, opponents, risk profiles, preparation strategies, and the meaning of success.

A metagame has its own goals, strategies, and rules. Crucially, it only shapes the game beneath it when its incentives flow downward and alter an agent’s reasons for choosing one strategy over another.

The rules of the lower game do not change — hockey, chess, markets, and scientific methods remain what they are — but the meaning of winning inside them can shift when a higher game imposes new rewards or penalties.

A metagame shapes a lower game by changing:

which strategies a player finds worthwhile,

which outcomes the player optimizes for,

and which risks or trade‑offs become acceptable.

If the incentives of the higher game do not propagate downward, the levels remain independent.

Most people spend their lives playing local games without ever noticing the metagames that govern them.

4. How Metagames Mislead Us

In any complex system—politics, science, technology, social networks—mistakes often come from misidentifying the game. People think they are rewarded for truth when the metagame rewards loyalty. They think they’re rewarded for virtue when the metagame rewards coalition membership. They believe they’re rewarded for originality when the metagame rewards conformity.

Once you see the metagame, these puzzles dissolve. What once looked irrational becomes legible.

5. How Far the Ladder Goes

Games always embed within larger games. Tactical decisions sit inside strategic plans; strategies sit inside cultural norms; cultural norms sit inside evolutionary pressures.

The ladder goes a long way up, but it doesn’t go up forever. It eventually reaches a level at which the sequence stops—not because we lack imagination, but because we hit the fundamental constraint that makes games possible at all.

This post is about seeing the ladder itself. Understanding the structure of nested games sets the stage for understanding the higher‑order forces that ultimately govern them.

6. How to Use This Lens

Once you understand that every activity sits inside a larger game, behavior becomes easier to interpret. Incentives that once seemed opaque now make sense. Conflicts that appeared irrational reveal their structure. Institutions that behave strangely become legible once you identify the higher‑level game they are actually optimizing for.

You can use this lens immediately:

to analyze decisions in your own life,

to understand the incentives inside groups or professions,

to identify why institutions pursue goals orthogonal to their stated purpose,

and to recognize when you are being pulled into someone else’s game.

Seeing games within games is a tool of clarity. Once you have it, you start noticing the hidden architecture behind choices, incentives, and behaviors everywhere you look.

7. Closing

This has been an introduction to the idea that everything you do occurs within a layered structure of games and metagames. Understanding that structure doesn’t make life simpler, but it does make it far more comprehensible. And once you can see the layers, you can begin choosing which ones you want to play.