Gender As Performance

How a single phrase became the battlefield of two worldviews.

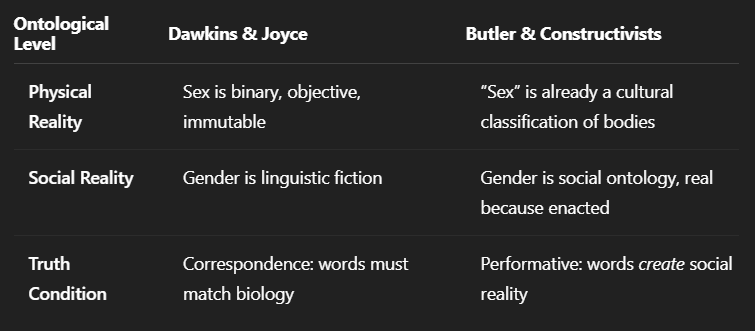

In Richard Dawkins’ recent Poetry of Reality conversation with Helen Joyce, both thinkers demonstrate a clarity of biological reasoning that is almost surgical—and yet they still speak past their opponents. Their discussion reveals a deeper confusion that infects the entire public discourse on gender: two opposing camps using the same words to describe completely different realities.

When Joyce says gender is performative, she means it as critique—a polite way of calling it make-believe. When Judith Butler said the same thing in Gender Trouble, she meant it as ontology—a claim about how social reality itself is constructed. The sentence is identical; the metaphysics is inverted.

1. Two Senses of Performance

For Dawkins and Joyce, performance is imitation. A male person identifying as female is, in their frame, acting as something he is not. Biology defines the truth conditions; words and gestures can only obscure it. When they call gender a performance, they mean a falsehood enacted through language.

For Butler, performance is creation. Gender categories do not pre-exist our behaviors; they emerge from them. To perform womanhood is to constitute the very category of woman within a social field of expectations. The performance does not hide the truth; it makes the truth real.

Same verb, opposite causal direction.

2. Two Realities Colliding

This is why the conversation between biological realists and social constructivists never resolves. Each side accuses the other of denying reality—and both are right within their own ontology.

They aren’t disagreeing about evidence; they are disagreeing about what counts as evidence. One side treats language as description, the other as construction.

3. The Category Error

Public debate collapses these two planes into one. When realists hear “gender is performative,” they interpret it as license for delusion. When constructivists hear “sex is real,” they interpret it as political oppression. Neither translation is faithful.

The result is a mirror illusion: each side sees in the other the same sin it condemns—the substitution of ideology for reality. The real confusion is ontological, not moral.

4. Linguistic War, Not Moral War

Both camps are, in their own way, defending coherence:

The biologist defends the integrity of empirical categories.

The theorist defends the autonomy of linguistic and social ones.

The tragedy is that each side mistakes the other’s level of reality for bad faith. Dawkins thinks Butler denies biology; Butler thinks Dawkins denies social construction. Both are partly correct, because both absolutize their preferred domain of truth.

5. Toward a Clearer Frame

The stalemate persists because no one distinguishes descriptive categories (sex) from constitutive categories (gender) within a unified epistemology. As long as each side insists its domain is the only real one, discourse will oscillate between outrage and confusion.

The corrective insight is simple:

Sex is empirically real; gender is socially real. They occupy different ontological layers and require different truth conditions.

The war over gender is not about morality or science. It is about the ontology of words—whether language merely describes the world or helps build it. Until that question is made explicit, every argument will keep circling the same invisible axis of misunderstanding.