Great Progress

The fall of child mortality and the rise of hope

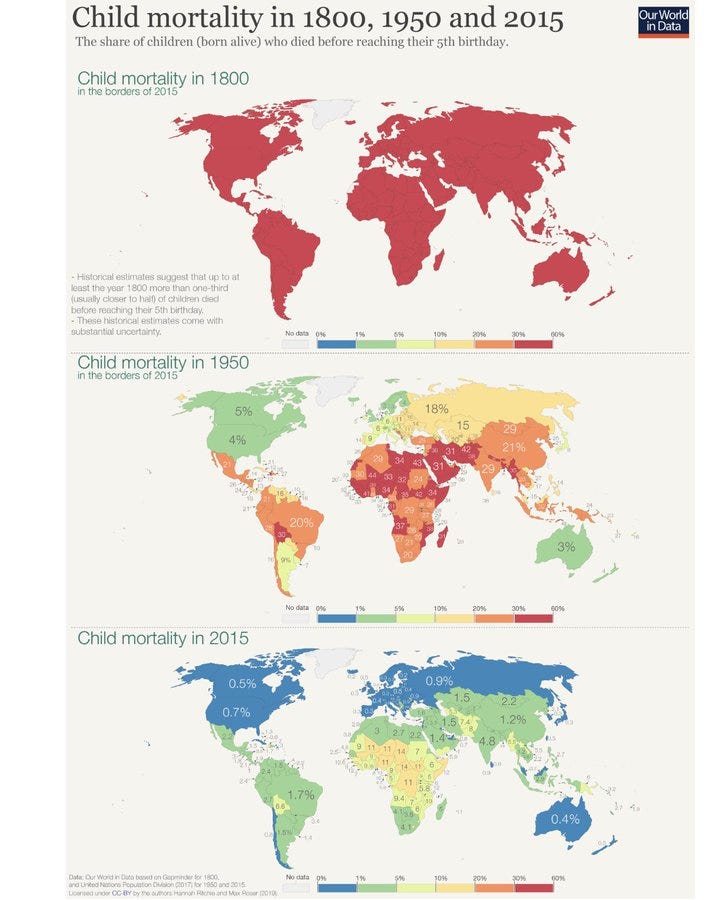

Child mortality is the most unforgiving of statistics. It measures the fraction of children who die before reaching their fifth birthday—a brutal index of how well a society protects its most vulnerable. In 1800, that fraction was not a fraction at all but a near-certainty: one in three, sometimes one in two, children never saw age five. Every family knew grief as intimately as life itself. The map of the world in 1800 is blood red for a reason—humanity lived in a constant state of loss.

By 1950, the picture fractured. The industrialized world—Western Europe, North America, Japan, Oceania—had slashed child mortality to under 5%. Antibiotics, vaccines, sanitation, and rising prosperity insulated their children from the epidemics and malnutrition that once claimed millions. But the rest of the globe still bled. Across Africa, India, the Middle East, and Latin America, between 20% and 40% of children still died young. The division was clear: modernity saved lives, and its absence cost them.

Fast forward to 2015. The transformation is unmistakable. In wealthy nations, child mortality dropped below 1%. In Latin America, East Asia, and the Middle East, survival rates approached the levels once reserved for elites. Even Sub-Saharan Africa, though still burdened, made extraordinary strides: 5–12% mortality, down from one-third only two generations before. Millions of lives spared, families unbroken, futures restored.

This is not an abstract improvement. It is the single most decisive measure of civilizational progress. A world in which childhood survival is the norm rather than the exception is a world that has fundamentally redefined what it means to be human. Where once life was nasty, brutish, and short, today life expectancy and human flourishing expand together. The child who survives today may become tomorrow’s scientist, artist, or revolutionary; their very existence bends history.

The causes of this triumph are neither mysterious nor ideological. Vaccines, antibiotics, oral rehydration therapy. Clean water, sanitation, nutrition. Maternal education and economic growth. Each step a practical intervention; together, a revolution in human destiny.

The story is not finished. Sub-Saharan Africa and parts of South Asia still carry the heaviest burdens, where poverty, weak health systems, and conflict conspire against further gains. But the direction is irreversible. Humanity has demonstrated that child mortality is not fate—it is policy, technology, and will.

The decline of child mortality is the strongest, most unambiguous argument against fatalism and cynicism. For centuries, death claimed children as a tax on life itself. Today, in most of the world, that tax has been abolished. Civilization’s scorecard is often disputed, but here the verdict is clear: progress is real, measurable, and monumental.