In Defense of Centrism

Why Moral Certainty Is a Governance Hazard

Centrism is usually treated as a punchline. From the left it is framed as moral cowardice. From the right it is dismissed as incoherence or surrender. In both cases, centrism is portrayed as a lack of conviction rather than as a considered response to political reality. That framing misses what centrism actually is when taken seriously.

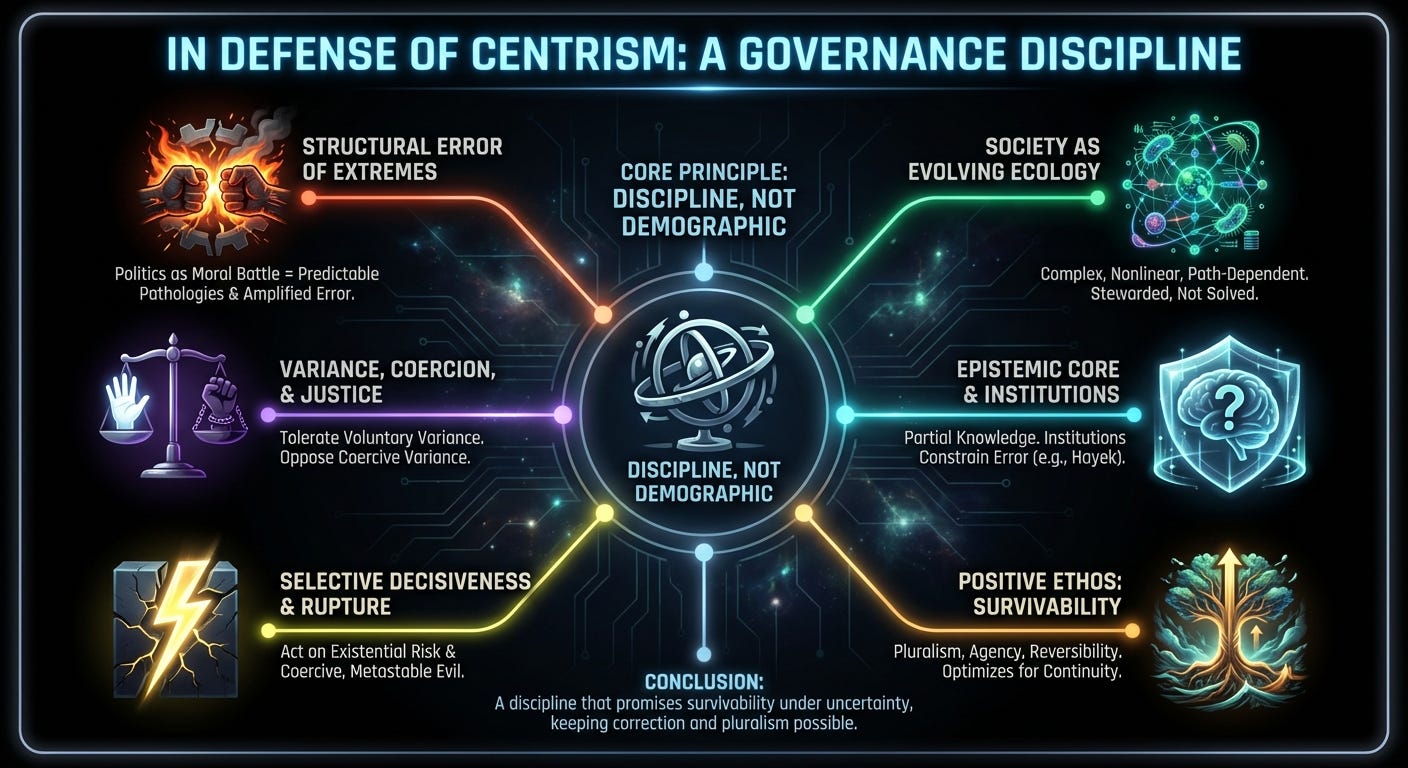

This essay defends centrism as a governance discipline shaped by complexity, uncertainty, and irreversibility. It does not defend moderation as aesthetic balance, compromise as virtue, or neutrality as an end in itself. It argues that political systems operate under constraints that reward variance tolerance, institutional friction, and humility about outcomes. Centrism emerges naturally once those constraints are treated as real.

Centrism as a discipline, not a demographic

The term centrism is often used sociologically, referring to a cluster of voters, parties, or elites. That usage is not what is defended here. Many self-described centrists act from inertia, donor capture, or simple risk aversion. Those failures belong to the practitioners.

Centrism, as defended in this essay, is a discipline. It is a method for governing under uncertainty. Like any discipline, it can be practiced well or poorly. Failure to meet its standards indicts the agent rather than the framework. Treating centrism this way aligns it with other axiomatic concepts such as agency, coherence, and survivability. Labels matter less than adherence to constraint.

The shared structural error of the extremes

Ideological extremes differ sharply in values, narratives, and policy goals. They converge on a deeper structural assumption about how politics works. Politics is framed as a moral battlefield. Progress becomes victory. Opposition becomes enemy. Power becomes the mechanism through which righteousness is enforced.

Once politics is framed this way, predictable pathologies follow. Tradeoffs lose legitimacy. Variance becomes injustice by default. Institutions appear as obstacles rather than safeguards. Confidence in moral intent substitutes for analysis of consequences.

Centrism rejects this framing. It treats politics as an ongoing coordination problem among agents with partially conflicting goals, incomplete information, and asymmetric power. In that setting, moral clarity does not dissolve complexity. It often amplifies error by licensing actions whose downstream effects are poorly understood.

Society as an evolving ecology

Political metaphors shape permissible action. The battlefield metaphor invites escalation. A mechanical metaphor invites control fantasies. A more accurate frame treats society as an evolving ecology of agents embedded in institutions.

Ecological systems exhibit properties that matter politically. They contain multiple actors with divergent incentives. They display path dependence, where early changes constrain later options. They produce nonlinear cascades, where small interventions can trigger disproportionate effects. They settle into local equilibria rather than global optima. They accumulate irreversible losses alongside slow recoveries.

Such systems cannot be solved. They can be stewarded, stressed, or destroyed. Interventions alter selection pressures and reshape incentives. Success often appears as resilience rather than perfection. Centrism aligns with this reality. Governance becomes an exercise in damage control and coordination rather than moral purification.

Variance, coercion, and justice

Variance appears wherever systems are allowed to operate. Differences in outcomes, capacities, preferences, and performance arise even under fair rules. Treating all variance as injustice leads to political strategies aimed at abolishing measurement rather than understanding causation.

This does not imply that all variance is acceptable. A crucial distinction separates variance produced by voluntary interaction from variance produced by coercive constraint. The former reflects decentralized choice under conditions of agency. The latter reflects systematic suppression of agency through credible threats of harm.

Centrism tolerates variance that emerges from voluntary processes. It treats coercively produced variance as a structural defect requiring intervention. This distinction supplies the moral compass. The question is not whether outcomes differ, but whether those differences arise from preserved agency or enforced constraint.

Once this distinction is explicit, tolerance ceases to look like complicity. It becomes selective intolerance of coercion.

The epistemic core of centrism

Centrism begins as an epistemic stance before it becomes a political one. Knowledge is partial. Incentives are complex. Feedback is delayed. Error scales with power.

Several commitments follow. Intentions do not guarantee outcomes. Second-order effects often dominate first-order gains. Policies should be judged by how they behave under stress, not by how they sound in principle. Authority should be distributed and constrained because confidence magnifies harm when it is wrong.

This posture aligns naturally with Conditionalism. Political claims only make sense relative to background conditions. Unconditional policies are incoherent because their effects depend on context. Centrism internalizes this insight and builds governance structures that expect revision rather than finality.

Institutions as ecological constraints

Institutions often attract criticism for being slow, imperfect, or unjust. Those critiques are frequently accurate. The function of institutions is not to instantiate moral truth. Their function is to constrain error and limit damage when judgment fails.

This insight appears clearly in the work of Friedrich Hayek, who emphasized knowledge limits and the dangers of centralized control. Institutions encode lessons learned through failure. They create friction precisely where confidence would otherwise run unchecked.

Centrism treats institutions as ecological scaffolding. Reform focuses on improving resilience and feedback rather than enforcing ideological purity. The objective is survivability under stress rather than optimization under ideal assumptions.

Metastable evil and justified rupture

Ecological stability is not sufficient for legitimacy. Some systems remain stable by systematically suppressing agency. Feudalism, caste systems, and apartheid persisted because they were internally coherent and brutally enforced. They represent metastable failure states.

Under a centrist discipline, such systems qualify as defects rather than equilibria to steward. When stability depends on coercion and irreversible agency suppression, disruption becomes justified even at significant risk. Abolition, civil rights movements, and decolonization required decisive rupture because incrementalism preserved injustice.

Centrism does not oppose disruption as such. It evaluates disruption by its failure modes and by whether it expands or destroys agency over time.

Selective decisiveness under existential risk

Centrism often attracts the charge of passivity. In practice it is selectively decisive. It supports strong action where failure modes are bounded and inaction produces irreversible loss.

Existential risks such as climate instability, uncontrolled AI deployment, demographic collapse, or institutional failure demand non-linear responses. Centrism does not oppose decisive action in these domains. It opposes action justified by moral certainty rather than by analysis of failure dynamics.

The discipline remains the same. Act where delay compounds harm. Constrain power where certainty outruns knowledge. Preserve reversibility where possible. Accept irreversibility only where alternatives collapse the future entirely.

Why centrism provokes hostility

Extremes depend on narrative clarity. They require villains, heroes, and historical destiny. Centrism denies moral monopoly. It treats opponents as constrained agents rather than embodiments of evil. It treats institutions as safety devices rather than sacred obstacles or disposable tools.

This denial frustrates movements built on identity and certainty. Centrism refuses to convert conviction into entitlement. The resulting hostility reflects psychological loss as much as political disagreement.

The aesthetics of boredom

Centrism often sounds dull. It offers no catharsis and no final victory. This is taken as evidence of weakness.

A different interpretation fits the evidence better. Systems that endure optimize for continuity and error correction rather than drama. The politics that keeps societies functioning rarely trends because it does not satisfy narrative hunger. Extremism compresses complexity into moral slogans. Centrism refuses compression.

A positive centrist ethos

Centrism affirms pluralism grounded in constraint. It values agency over purity. It treats coercion as a costly instrument rather than a moral reward. It emphasizes reversibility, feedback, and institutional memory.

This ethos accepts that no political arrangement resolves all tensions. Politics remains an ongoing coordination problem rather than a final reckoning. Progress appears as incremental improvement punctuated by necessary rupture when agency is systematically suppressed.

Postscript

Centrism, understood as a discipline, does not promise moral satisfaction. It promises survivability under uncertainty. It treats power as hazardous, certainty as brittle, and agency as the condition under which correction remains possible. In a world shaped by irreversible choices and incomplete knowledge, this posture is not timid. It is exacting. It asks political systems to remain governable even when they are wrong, and it asks political actors to design for that inevitability. That requirement does not inspire chants. It does something harder. It keeps open the space in which correction, pluralism, and future choice remain possible.