Luck Doesn't Justify Coercion

Rejecting Luck-Based Arguments for Redistribution

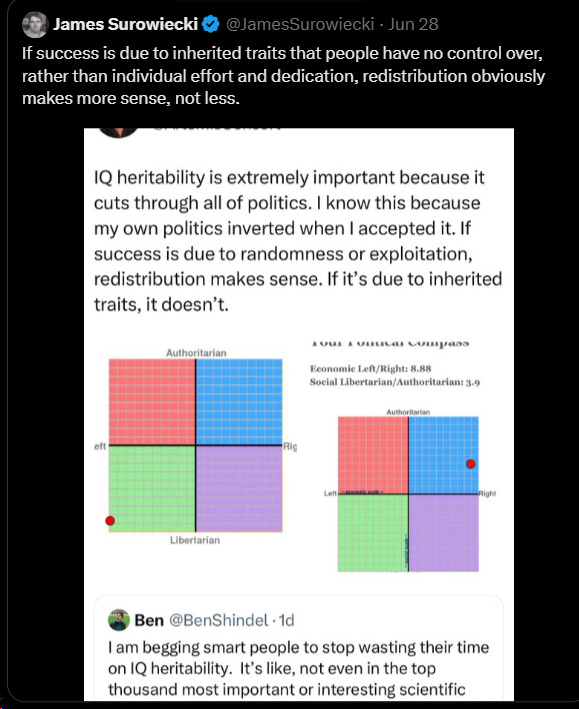

A recent social media debate highlights a common misunderstanding regarding redistribution and coercion. James Surowiecki argues that if success results primarily from inherited traits—something individuals have no control over—then redistributive policies become more justified. The assumption here is that unearned success morally obligates redistribution.

This perspective, while internally coherent within egalitarian or Rawlsian frameworks, fails under rigorous philosophical scrutiny when we clarify our ethical terms clearly, specifically regarding agency and coercion.

Agency, Luck, and Redistribution

We must differentiate clearly between two separate claims:

Success often depends significantly on luck (genetic inheritance, upbringing, environment).

Luck-based disparities justify coercive redistribution.

Claim 1 is true but ethically irrelevant for the justification of coercion. Whether someone's success arises from genetic inheritance, fortunate environmental circumstances, or deliberate personal effort, the origin of their success does not morally permit coercion against them. Coercion is defined precisely as a credible threat of harm used to gain compliance. Any redistribution involving coercion inherently reduces agency, which is intrinsically harmful and ethically impermissible.

Poverty, Not Inequality, Is the Problem

The underlying ethical issue is not whether success is earned or inherited, but whether individuals have sufficient agency. Poverty—the lack of basic agency to pursue meaningful choices—is genuinely harmful and must be addressed. However, inequality itself is not inherently problematic if it arises without coercion. Attempting to correct inequality through coercive redistribution introduces harm precisely because it restricts voluntary agency.

Voluntary Redistribution: Ethical and Effective

Redistribution that emerges voluntarily—through charitable giving, community cooperation, and non-coercive structures—is entirely ethical and commendable. It respects agency while effectively addressing genuine poverty and deprivation. Coercive redistribution, justified solely by appeals to luck or fairness, inevitably undermines the very agency we seek to enhance.

Conclusion

Neither genetic luck nor environmental luck ethically justifies coercive redistribution. A rigorous ethical framework places agency at its core, consistently rejecting coercion. Redistribution, to remain ethical and effective, must always be voluntary.