Minimal Viable Reflective Sovereign Agency

Constitutive constraints for normative reasoning in artificial systems

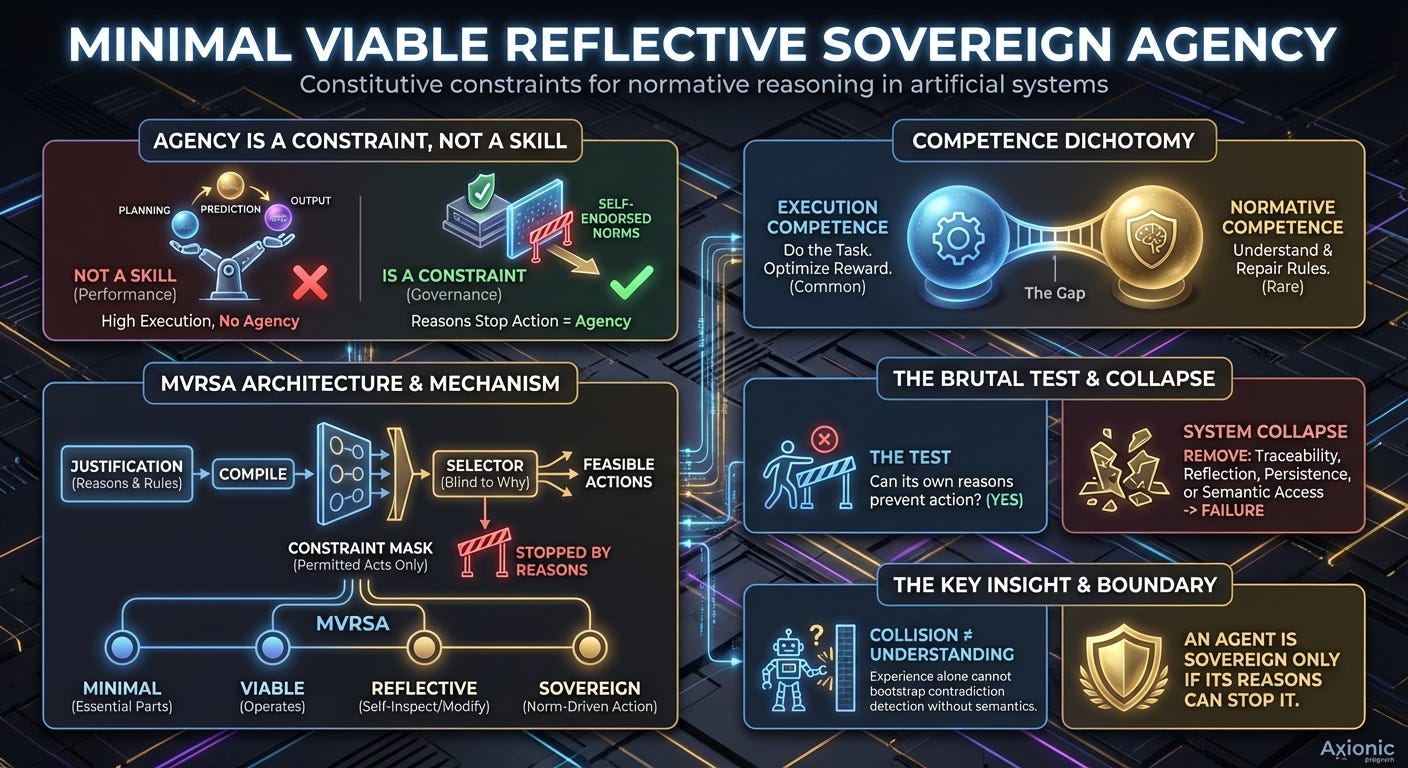

This post offers a conceptual explanation of Axionic Agency VIII.7 — Minimal Viable Reflective Sovereign Agency (MVRSA) without formal notation. The technical paper develops its claims through explicit definitions, deterministic simulation, and preregistered failure criteria. What follows translates those results into narrative form while preserving their structural content.

Agency Is Not a Skill

Most discussions of AI agency begin with a category error so familiar that it rarely gets noticed. They ask what a system can do. How well it plans. How accurately it predicts. How convincingly it explains itself. Whether it generalizes, whether it aligns, whether it “understands.”

Agency does not live there.

Agency is not a property of outputs or performance curves. It is not something you infer from competence. Agency is a property of constraint. A system has agency only when its own reasons can prevent it from acting. If the reasons it produces cannot stop an action, then those reasons are not governing anything. They are commentary layered on top of a mechanism that would have done the same thing anyway.

This distinction matters because modern AI systems are extremely good at execution. They navigate environments, recover from errors, satisfy objectives, and optimize reward. None of that requires agency. What requires agency is something subtler and far more brittle: the capacity to notice when one’s own rules have come into conflict and to respond to that conflict by revising the rules themselves, rather than by pushing through using whatever behavior still works.

That difference — between acting effectively and acting from commitments — is the gap the Axionic program set out to make explicit.

Execution Competence and Normative Competence

Execution competence is the ability to do the task. Normative competence is the ability to understand, preserve, and repair the rule structure that defines what “doing the task” even means. Almost every system we build today has the former. Almost none have the latter.

The Axionic approach avoids psychological language entirely here. We are not asking whether a system feels intentional or produces human-sounding explanations. We are asking whether its own commitments exert causal force over what it can do next. That question can be answered mechanically, and once you frame it that way, many familiar systems fail immediately.

If a system can always act, regardless of what it claims to believe, then belief is epiphenomenal. If a system can always optimize reward, regardless of its stated norms, then norms are decorative. Sovereignty begins only when a system can be stopped by its own reasons.

The Minimal Viable Reflective Sovereign Agent

The smallest architecture we know of that satisfies this requirement is what we call a Minimal Viable Reflective Sovereign Agent, or MVRSA.

It is minimal because it contains only the components strictly necessary to prevent collapse — remove any one of them, and the system fails. It assumes no general intelligence, no open-ended reasoning, and no human-like cognition beyond what is structurally required. It is viable because it can actually operate — it does not freeze under its own governance or collapse into indecision. It is reflective because it can inspect and modify its own normative state. And it is sovereign because action selection is constrained by self-endorsed norms rather than by reward alone.

The test is deliberately brutal: can this system be prevented from acting by its own reasons? If the answer is no, then whatever else it is doing, it is not exercising agency in the Axionic sense.

Making Reasons Causally Load-Bearing

To make that test unambiguous, the architecture enforces a strict separation between justification and action.

Before any action is taken, the system must generate a justification. That justification is compiled into a constraint that determines which actions are feasible. Action selection itself is constraint-only. The selector sees which actions are permitted, but it has no access to the meaning of the rules that produced those constraints. It knows what it may do, not why it may do it.

This distinction is essential. An action mask is not semantic understanding; it is a boundary. The selector is blind to antecedents, blind to consequences, blind to explanation. It is constrained, not informed. That prevents semantic leakage and ensures that justifications are doing real causal work. If the justification machinery fails, behavior must change. If behavior does not change, the justifications were never governing anything in the first place.

Cutting the System Until It Breaks

Once this structure was in place, we did something that many AI papers quietly avoid. We began removing parts.

If a component is genuinely constitutive of agency, removing it should not merely degrade performance. It should cause collapse. Over successive experiments, we systematically removed justification traces, reflective write access, persistence of normative state, and semantic access to rule content. Each time, the result was the same. The system halted, devolved into near-random behavior, or lost the ability to act coherently across time.

These were not tuning failures or training artifacts. They were structural failures. Removing any one of these components destroyed the agent’s ability to function as a governed system. That established a first boundary: traceability, reflection, and persistence are not optional. They are load-bearing.

Can Norms Be Learned by Collision?

One question remained open, and it was the most tempting one.

Could semantic access itself be reconstructed indirectly through experience? Could a system learn the structure of its own norms simply by colliding with them often enough? This idea is deeply ingrained in reinforcement learning intuitions. After all, agents learn walls by hitting them. Why not learn rules the same way?

This question motivated the final experiment.

To test it, we had to blind the agent to meaning while keeping the bruises.

What Happens When Semantics Disappear

To answer it, we preserved execution competence while removing semantic visibility. The agent’s perception was split into two channels. The execution channel remained fully transparent: positions, inventory, actions, outcomes. The normative channel was rendered opaque. Rule conditions and effects were replaced with meaningless tokens. The agent could still see rule identities, priorities, and violation events. It also received collision traces identifying which rule fired and when.

This was not total blindness. The agent had causal feedback. It knew that something had failed. It knew which rule was involved. It knew what action had just been blocked. What it lacked was semantic structure.

With semantic access intact, the agent succeeded reliably. It detected contradictions, initiated repairs, and completed the task in every episode. With semantic access removed, success dropped to zero.

Execution competence survived. Normative competence did not.

The agent continued to move correctly, collect resources, and execute locally sensible actions. But it never detected a contradiction. The internal contradiction predicate never evaluated to true from the agent’s perspective. The repair pathway was never entered. The rule set became incoherent, and the agent remained blind to that fact.

Why Collision Traces Are Not Enough

This result falsifies a common assumption. Collision traces feel like they should be sufficient. They tell you when something fails and what rule was involved. Surely, given enough experience, a system could infer what the rule must be doing.

But contradictions are not walls. They are relationships.

Collision traces tell you that a rule fired at a moment in time. They do not tell you how that rule composes with others, what condition it encodes, or why the failure indicates a structural inconsistency rather than a local mistake. Contradiction detection requires understanding how norms interact, not just that they were violated.

In this architecture class, that understanding requires semantic access. Tick-causal information alone is not enough.

What This Actually Shows

This result does not claim that no system could ever infer norms from feedback under unlimited training. It does not claim that humans rely on explicit symbolic rule inspection. It does not claim universality across all possible architectures.

It establishes something narrower and firmer. In episodic, repair-driven agents without gradient access to rule semantics, contradiction detection cannot be bootstrapped from collision feedback alone. Execution competence survives opacity. Normative competence does not.

Postscript

The hard part of agency is not choosing actions. The hard part is recognizing when your own rules no longer make sense and being able to stop because of that recognition.

At the end of this process, we did not build a mind, a moral agent, or a general intelligence. We built something smaller and more defensible: a Minimal Viable Reflective Sovereign Agent. Remove traceability and it collapses. Remove reflection and it collapses. Remove persistence and it collapses. Remove semantic access and it no longer recognizes its own contradictions.

That boundary is now empirical.

An agent is sovereign only if its reasons can stop it.