Mythogenesis

Case studies in how legend overgrows fact

History is a fragile thing. It begins as a few scattered details, half-remembered by contemporaries and recorded with varying degrees of care. But human imagination is ravenous. It does not tolerate bare kernels of fact; it demands story, pattern, meaning. What begins as a name and a rumor can, under the right cultural conditions, grow into a legend that dwarfs the underlying man.

One way to understand this process is through the lens of the motte-and-bailey. The motte is the modest, defensible claim: the dry fact historians can support. The bailey is the expansive, ambitious structure of meaning, myth, and ideology that flourishes on top of it. When challenged, defenders retreat to the motte; when unchallenged, they inhabit the bailey.

Three figures illustrate this spectrum: Arthur, Socrates, and Jesus. Each began as a probable historical core, but each was swiftly overtaken by the myths that colonized his memory.

Arthur: The Vanishing Hero

King Arthur’s historicity is the weakest of the three. At best, he was a post-Roman warlord in the fog of Britain’s Dark Ages. At worst, he never existed. But the Arthur we know — Camelot, Guinevere, Excalibur, Avalon — is not the Arthur of archaeology. It is the Arthur of Geoffrey of Monmouth, Chrétien de Troyes, and Malory. Legend colonized history until only a few specialists even care whether there was a real commander at the core. Arthur’s motte is feeble, but his bailey — a romance of national identity — overwhelms it.

Socrates: The Philosophical Projection

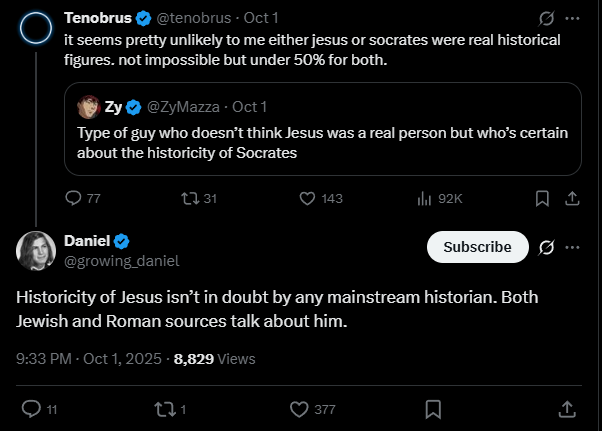

Socrates, unlike Arthur, almost certainly lived. His existence is vouched for by multiple contemporaries, including hostile ones. Yet what survives of him is not the man, but the Platonic Socrates, the Xenophontic Socrates, the comic Socrates of Aristophanes. Each is a projection, a mask. The historical Socrates is buried beneath layers of philosophical agenda. His motte is strong, but his bailey — the eternal questioner, the paragon of reason, the martyr for truth — is an idealization that colonizes our understanding of him.

Jesus: The Cosmic Savior

Jesus occupies the extreme case. The motte is secure enough: a Jewish preacher executed under Pilate, mentioned in Roman and Jewish sources. But the bailey is cosmic. Within decades he is reimagined as miracle-worker, Messiah, Son of God, Logos incarnate. His followers grafted apocalyptic visions, messianic prophecies, and Hellenistic theology onto the faint outlines of a Galilean rabbi.

Where Arthur gained chivalry and Socrates gained philosophy, Jesus gained the universe. The kernel of a man became the cornerstone of empires, crusades, cathedrals, and metaphysical systems. No other figure shows so vast a gap between what can be defended historically and what has been believed culturally.

The Lesson of Colonized History

History does not remain history. It is colonized by legend, and legend thrives not because it is true, but because it is useful. Socrates became philosophy’s patron saint. Arthur became Britain’s national myth. Jesus became the axis of salvation.

The motte is the sliver of fact that defends against skeptics. The bailey is the cultural fortress built on top. If we want to understand how humans turn memory into meaning, and meaning into power, we must study not only the men who lived — but the legends that colonized them.