Politics as Phase Space

How Axionic agents define the region where agency survives

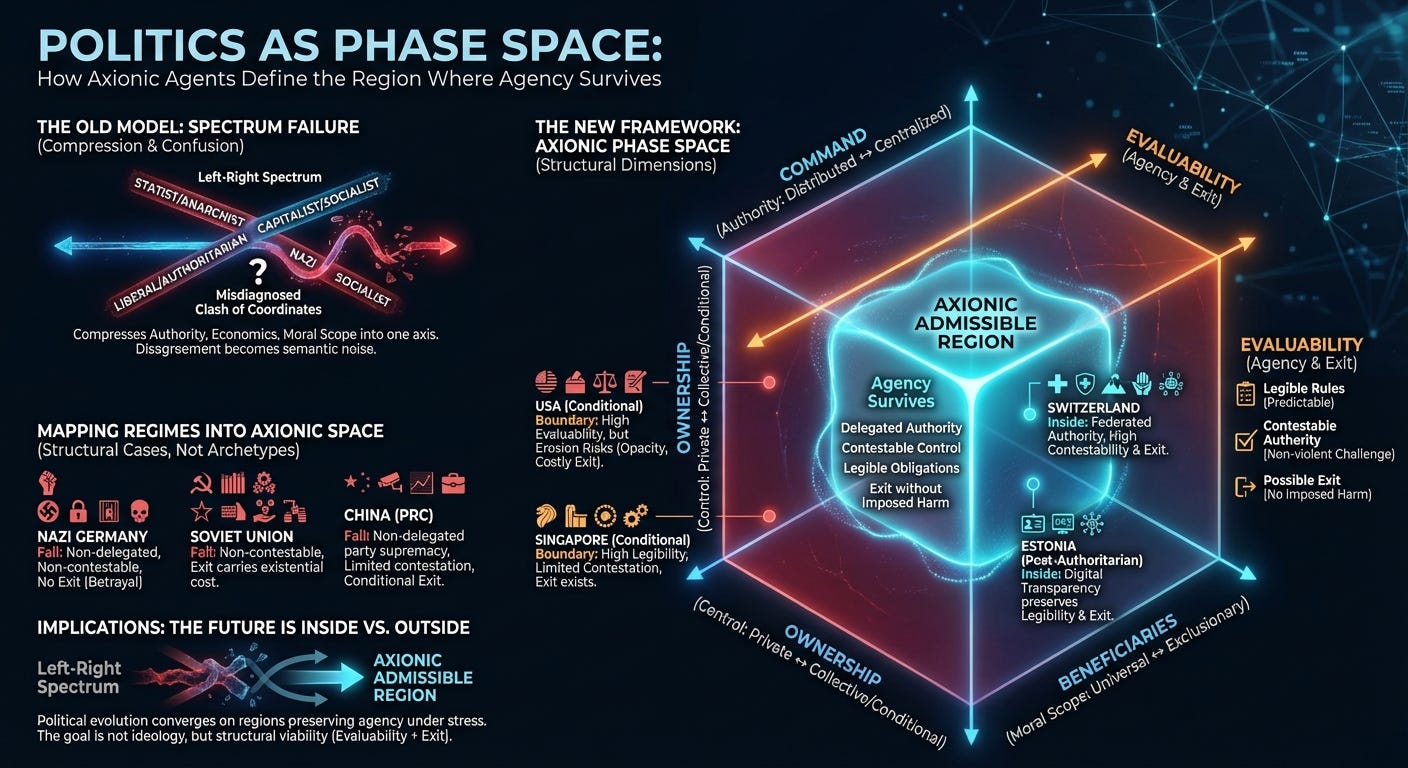

The failure mode we keep repeating

Most political disagreement is misdiagnosed. What looks like a clash of values is usually a clash of coordinate systems. People argue as though they are disagreeing about outcomes, when in fact they are reasoning inside a model that has already erased the distinctions doing the real work.

That model is the left–right spectrum.

It compresses authority, economics, moral scope, and coercion into a single axis and then forces every political system to occupy a point along it. Once this compression occurs, confusion is no longer an accident. Systems that differ radically in structure become rhetorically interchangeable, while systems that share deep similarities are treated as moral opposites.

The familiar dispute over whether the Nazis were “socialist” is not a historical curiosity. It is a predictable artifact of a representational failure. The same collapse appears in contemporary arguments about taxation, welfare, regulation, markets, nationalism, and global governance. The spectrum cannot encode the distinctions people are implicitly arguing about, so disagreement degenerates into semantic noise.

If political analysis is to regain traction, the spectrum has to be abandoned.

Asking the questions that actually classify regimes

Political systems are not defined by what they call themselves. They are defined by how power is arranged and enforced.

Any classification that survives contact with reality must answer three questions independently. One concerns authority: where command ultimately resides and how far it reaches. Another concerns economic control: who determines the use of productive resources and future economic states. The third concerns moral scope: who the system is for, and who it is willing to exclude or instrumentalize.

These questions vary independently in the real world. Authority can be centralized or distributed regardless of how ownership is allocated. Ownership can be private, collective, or conditional regardless of who counts morally. Moral scope can be universal, national, class-based, or exclusionary without fixing either authority or ownership.

Political rhetoric routinely collapses these distinctions because doing so is persuasive. Analysis cannot afford that convenience.

Once attention shifts from ideological labels to these structural relations, regimes that previously seemed paradoxical become straightforward to classify.

A political phase space instead of a spectrum

The simplest faithful representation of political systems is not a line but a space with multiple independent dimensions.

One dimension tracks command. It captures whether authority is distributed or centralized, whether it is reversible or absolute, and whether it is grounded in delegation or treated as intrinsic. Another dimension tracks ownership. It captures who controls productive resources, how contestable that control is, and whether economic power can be reassigned without coercion. A third dimension tracks beneficiaries. It captures who the system treats as morally salient and who it is willing to exclude.

This alone dissolves much of the confusion that plagues political discourse. Systems that were previously misclassified fall naturally into place once authority, ownership, and moral scope are allowed to vary separately.

Yet even this three-dimensional model remains incomplete.

The missing variable: evaluability

Two regimes can occupy similar positions along the axes of command, ownership, and beneficiaries while producing radically different lived experiences. One allows planning, dissent, and refusal. The other induces opacity, caution, and fear. The difference does not lie in ideology. It lies in whether agents can model the system acting on them.

Evaluability measures whether rules are legible before they bind, whether obligations can be anticipated, whether authority can be challenged without violence, and whether participation can be refused without catastrophic loss. Exit is the operational test.

Exit costs may be high. Axio only disqualifies systems where exit is blocked or punished by credible threats of imposed harm, rather than by the ordinary loss of local advantages, relationships, or opportunities that accompany relocation or withdrawal in any social order.

This variable explains why some systems feel navigable even when authority is strong, and why others feel suffocating even when they claim benevolence. It also explains why many political theories fail to predict lived experience: evaluability is rarely modeled explicitly.

Axio as a meta-framework

Axionic agents do not occupy a point in political space. They are not left, right, statist, anarchist, capitalist, or socialist. They operate at a different level of abstraction.

Axio is a meta-framework that constrains political systems by agency-preservation, independent of their distributive, cultural, or moral goals. It does not specify which political order should be preferred. It specifies which political orders remain compatible with the continued existence of agents who can model, contest, and revise the structures acting upon them.

Axio is normative in the sense that it values agency. It does not claim moral objectivity, inevitability, or physical law. The phase-space language used here is structural modeling, not a claim that politics reduces to physics.

The Axionic admissible region

From an Axionic perspective, political systems carve out regions of a larger phase space. Some regions preserve agency under variation and stress. Others do not.

The admissible region is defined by structural conditions rather than policy choices. Authority must be traceable to agent-level delegation rather than terminating in sacred or self-justifying power. Control relations must remain challengeable without violence. Participation must not be enforced through credible threats of imposed harm that an agent did not endorse under non-manipulated conditions. Obligations must remain legible in advance rather than appearing retroactively or opaquely. Exit must remain possible without destroying an agent’s capacity to act.

These conditions do not select a single political form. They license a range of arrangements, including markets, cooperatives, federations, voluntary collectivities, and even temporary states. What they exclude are systems that close off contestation, collapse evaluability, or convert participation into coercion.

A system leaves the admissible region the moment any one of these conditions fails.

Mapping real regimes into Axionic space

Once political systems are treated as points in a multi-dimensional space, the value of the framework becomes empirical rather than rhetorical. Real regimes stop being moral archetypes and start becoming structural cases.

Consider Nazi Germany. Authority terminated in personalist sovereignty. Delegation existed rhetorically but not structurally; power could not be reconstructed back to agent endorsement in any meaningful sense. Economic ownership formally remained private, yet control was contingent on political obedience, eliminating contestability. Moral scope was explicitly exclusionary, evaluability collapsed under retroactive law and discretionary enforcement, and exit was treated as betrayal. The system violated every Axionic condition simultaneously, placing it far outside the admissible region.

The Soviet Union occupied a different part of the phase space yet exited the admissible region for related reasons. Authority consolidated into party sovereignty without reversible delegation. Ownership centralized under the state without meaningful challenge mechanisms. Moral scope was framed in class terms but imposed rather than chosen. Evaluability existed at the level of ideology and formal rules, while outcomes depended on discretionary enforcement and political alignment. Exit carried existential cost. The system failed on delegability, contestability, and exit, which suffices for exclusion regardless of intent.

The People’s Republic of China illustrates why one-dimensional models struggle. Economic ownership is mixed and pragmatic. Market mechanisms coexist with extensive state direction. The decisive failures lie elsewhere. Authority terminates in party supremacy without reconstructible delegation. Contestation is tightly bounded. Evaluability is selectively high for compliant agents and sharply degraded for dissenters. Exit remains conditional and politically constrained. Economic flexibility does not compensate for structural treatment of agency.

Liberal democracies require more careful handling because they often sit near the boundary rather than clearly inside or outside. The United States illustrates this. Authority is constitutionally delegated and formally reversible. Ownership remains largely private and contestable. Moral scope is individualist in principle. Evaluability remains high enough to permit planning and dissent, though it shows signs of erosion through regulatory opacity and administrative sprawl. Exit is possible but costly, with costs unevenly distributed. From an Axionic perspective, this is a conditional case whose status depends on whether coercion thresholds and exit penalties remain below agency-destroying levels.

By contrast, Switzerland sits comfortably inside the admissible region. Authority remains federated and traceable through delegation. Ownership is private and contestable. Moral scope is locally grounded rather than universalized. Evaluability is unusually high due to transparency, decentralization, and frequent consent refresh. Exit exists both formally and practically. Its Axio-compatibility rests on structure rather than virtue.

Singapore presents a conditional case. Authority is centralized but predictable. Ownership remains private under clear rules. Evaluability is high, which makes the system navigable despite limited political contestation. Exit exists and is widely exercised. Singapore remains admissible not because contestation is strong, but because alternative agency-preserving mechanisms partially compensate. This placement is brittle. Further erosion of contestability or exit would matter disproportionately.

Post-authoritarian republics such as Estonia show how digital transparency and legible governance can preserve evaluability at scale. Authority remains reconstructible, ownership contestable, and exit practical. These cases demonstrate that complexity alone does not destroy agency; opacity does.

Stateless and quasi-stateless systems clarify the lower bounds of command. Open markets, open-source ecosystems, and voluntary protocols often maximize evaluability and exit by default. Their primary risk arises when network effects convert coordination into dependency. When exit becomes nominal rather than real, formally voluntary systems can drift out of the admissible region. The Axionic test applies here as strictly as it does to states.

Across these cases, a pattern emerges. Systems fail Axio because authority becomes irreducible, contestation collapses, or exit turns into a credible threat of imposed harm. Systems remain admissible when those failure modes are structurally blocked, regardless of ideology.

What this framework explains

Once this structure is visible, several persistent confusions dissolve. Coercion justified by benevolent intent still fails when it destroys exit or evaluability. Inequality alone does not disqualify a system when agency remains intact. Prosperity does not imply legitimacy when participation is compulsory. Moral universalism becomes suspect when it overrides consent in the name of aggregate outcomes.

Many political disputes persist because participants argue across different dimensions without realizing it. The admissible-region framing forces those dimensions into view.

Implications for political evolution

Political evolution is unlikely to converge on a single ideology. It is more likely to converge on regions that preserve agency under competition, scale, and stress.

Digital governance, modular citizenship, protocol-based coordination, and exit-driven competition between systems make sense in this frame. They are not utopian aspirations. They are structural responses to the pressure imposed by evaluability and exit.

The future of politics is not left or right. It is inside or outside the region where agency remains viable.

Postscript

Once politics is understood as a phase space, the task changes. The question becomes which regions preserve agency under stress and which reliably collapse it. Axionic agents define that distinction by enforcing constraints rather than preferences. Within the admissible region, pluralism is possible. Outside it, domination emerges regardless of intent. Political clarity begins at that boundary.

The evaluability dimension is prob ably the most underappreciated variable in political analysis. When I think about why Singapore feels navigable despite centralization, it's exactly that transparency point - rules are clear even if contestation is limited. The Axionic admissible region concept is useful because it sidesteps the usual ideological debates and focuses on whether agents can actually model the system. That structural approach makes way more sense than endless left-right arguments.