Speech Is Not Violence

Free expression as a bulwark against bloodshed

1. The Murder That Proves the Point

Charlie Kirk’s assassination in Utah is more than a tragedy. It is a chilling vindication of a warning many of us have been making for years: that collapsing the distinction between speech and violence is an invitation to actual violence. When a society accepts the premise that “words are violence,” it legitimizes reprisal with fists, batons, and bullets. Kirk was not killed because he shot anyone, burned anything, or stormed a building. He was killed because of what he said, what he represented, and the political identity attached to his speech.

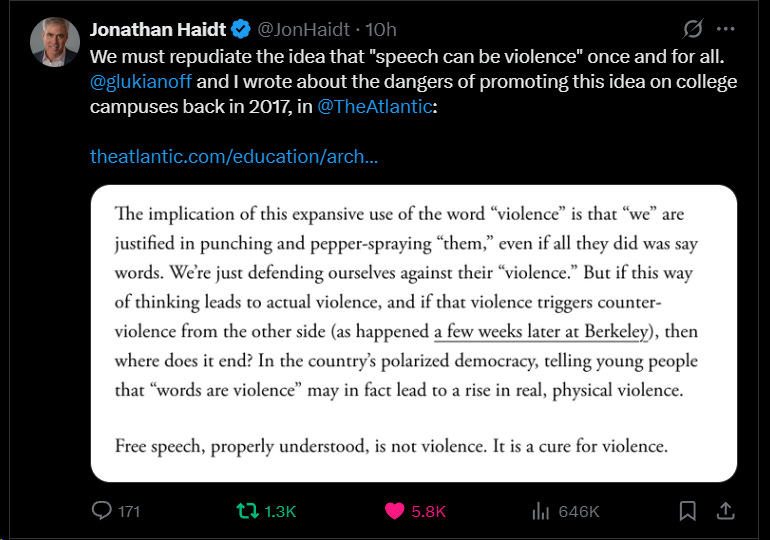

2. Haidt and Glukianoff’s Warning

Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff flagged this danger back in 2017. Their argument was simple:

If speech is violence, then violent retaliation is self-defense.

Once people believe they are fending off “harm,” they feel justified in escalation.

In a polarized society, this logic spirals quickly into reciprocal violence.

The antidote is to recover the older principle: free speech is not violence. Properly understood, it is a cure for violence.

This wasn’t abstract philosophy. We saw it on campuses when speakers were met with pepper spray and riots under the banner of “defending” against hateful words. Berkeley was the test case. Utah has now become the proof case.

3. Why This Distinction Matters

Speech and violence differ ontologically. Words persuade, insult, offend, and provoke—but they do not directly break bones or spill blood. Violence, by contrast, is physical force against bodies. When we erase this line, we hand demagogues and extremists a blank check: they can declare any dissent “violent” and answer it with force.

This is not a left vs. right issue. The left calls conservative speech “hate speech,” the right calls progressive speech “cultural subversion.” Both sides flirt with the same error. Once rhetorical enemies are recast as existential threats, the next step is someone pulling a trigger.

4. The Psychology of Justification

Every act of political violence requires a story that legitimizes it. The assassin tells himself:

I am under attack.

My enemy is not merely wrong, but dangerous.

Words wound like weapons, so weapons are a fair response.

This logic is seductive because it transforms aggression into virtue. The shooter becomes not a murderer, but a defender. And once this mental shift occurs, the taboo against killing collapses.

The danger Haidt highlighted is not that everyone will believe “speech is violence.” It is that enough unstable individuals will, and in a polarized culture that’s all it takes.

5. Free Speech as a Safety Valve

History shows that suppressing speech breeds violence. The Inquisition silenced heretics with fire. The Soviets silenced dissidents with gulags. In each case, ideas did not vanish—they metastasized underground, returning with greater fury.

By contrast, open societies treat words as the battlefield. If people can argue, they need not fight. Speech, by airing grievances, diffuses resentment before it hardens into rage.

Free speech is not violence. It is the mechanism by which violence is avoided.

6. The Duty of Public Figures

Every public intellectual, media figure, and political leader faces a choice. We can model the distinction between words and violence—or we can collapse it for short-term advantage. When we tell followers that they are being “harmed” by speech, we are laying kindling. When we insist that offensive views are a mortal threat, we are handing someone a match.

The assassin of Charlie Kirk pulled the trigger. But the cultural story that “words wound like weapons” helped him load the rifle.

7. The Principle We Must Defend

To honor both Kirk’s life and the principle of liberal democracy, we must draw the line in bright ink:

Speech is not violence.

Violence is not speech.

To conflate the two is to justify tyranny and bloodshed.

Free expression, properly defended, is not a threat. It is civilization’s greatest safety valve—the cure for violence.