The Case for Reality

Mapping Hoffman’s illusions against the hidden background assumptions

Donald Hoffman has a flair for the dramatic. His 2019 book The Case Against Reality tells us that everything we see is a lie: the world of colors and objects, of space and time, is nothing more than a user interface designed by evolution. The metaphor is irresistible: just as your desktop icons hide the messy circuits of silicon, your visual field hides the quantum froth beneath.

Readers typically respond in one of two ways. Some nod in awe, as though Hoffman has revealed a cosmic conspiracy. Others scoff, dismissing him as another idealist in scientific drag. Both reactions miss the point. The right question isn’t “Is Hoffman right?” but “Under what conditions would Hoffman be right?”

This is where Conditionalism shows its power. Every truth claim presupposes background conditions. Interpretation is never unconditional; it always runs on hidden rails. To test a sweeping theory like Hoffman’s, we don’t choose between True and False. We expose the conditions under which his thesis holds, and the conditions under which it collapses.

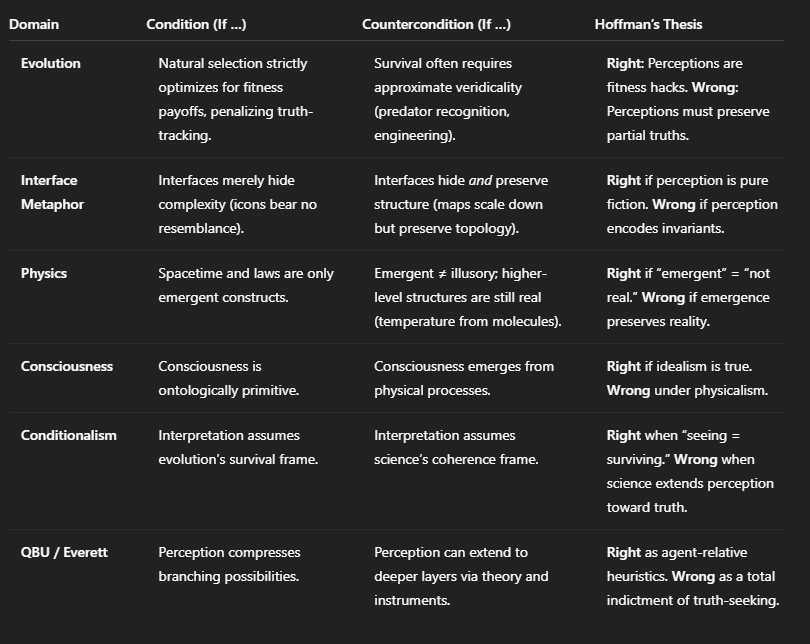

The Conditional Matrix

Here’s the skeleton of Hoffman’s case, laid out as conditions:

Worked Example: The Interface Metaphor

Hoffman’s most effective rhetorical move is the desktop metaphor. He says: just as your computer icons are convenient fictions—tiny blue folders and trash cans that conceal circuits and voltages—so too your perceptions are convenient fictions that hide the machinery of physics.

Conditionalism cracks this open.

Condition A: If interfaces only hide, then the metaphor works. Your icons tell you nothing about transistors, just as your perception of an apple tells you nothing about quantum fields. The apple is an icon, not a thing.

Condition B: But if interfaces also preserve structural invariants, then the metaphor is fatally misleading. A subway map is an interface, but the topology it encodes is real enough that you’ll get lost if you treat it as fiction. Your perception of an apple may not mirror physics, but it still preserves causal constraints (solid vs. liquid, edible vs. toxic). It’s not pure fiction; it’s compressed structure.

Hoffman’s metaphor is powerful precisely because he sneaks in Condition A while most readers tacitly assume Condition B. Conditionalism exposes the substitution.

Worked Example: Physics as Emergent

Another of Hoffman’s recurring moves is to cite cutting-edge physics. He likes to point to Nima Arkani-Hamed’s amplituhedron, or the growing consensus that spacetime is emergent in quantum gravity. His conclusion: if spacetime itself is emergent, then what we perceive—tables, trees, stars—isn’t really there. It’s just our interface.

Again, Conditionalism makes the hidden condition explicit.

Condition A: If “emergent” means “illusory,” then Hoffman’s claim follows. Spacetime is a trick of the eye, not part of the furniture of reality. Our perceptions of objects in space are doubly fictional: fictions within a fiction.

Condition B: But if “emergent” means what physicists actually mean—higher-level structures that are real even though they derive from deeper laws—then Hoffman’s leap is illegitimate. Temperature emerges from molecular motion, but that doesn’t mean temperature is unreal. It means it’s a macro-level regularity with predictive and explanatory power. By analogy, spacetime can be emergent without being fictional.

Conditionalism exposes the equivocation. Hoffman swaps the physicist’s technical sense of “emergence” for the layperson’s sense of “illusion.” Once that move is unmasked, his case loses its force.

Everettian Navigation

This is where the Quantum Branching Universe framework offers a cleaner model. In Everettian physics, perception is indeed a heuristic: a way of compressing the branching welter of possible worlds into a coherent agent-relative experience. We don’t see the universal wavefunction. We see a navigational slice of it.

But unlike Hoffman, I don’t need to claim that perception is nothing but fiction. Under Everett, perceptions are partial but structurally anchored: they track enough of reality’s constraints to keep an agent alive, and science extends those anchors deeper into the branching structure.

Conditionalism in Action

Hoffman’s Case Against Reality makes for a vivid illustration of how Conditionalism works. He dazzles with metaphors and physics references, but once we lay out the conditions, his claims shrink to size.

He is right under Condition A: if evolution always punishes truth, if interfaces are pure icons, if emergence equals illusion, if consciousness is primitive.

He is wrong under Condition B: if survival requires approximate veridicality, if interfaces preserve structure, if emergent levels are real, if consciousness is derivative.

The trick is not to choose sides, but to recognize the hidden switch: change the background conditions, and the verdict flips.

That is the power of Conditionalism. It doesn’t merely arbitrate disputes; it dissolves them into a map of assumptions. It shows precisely when a theory is compelling and when it’s empty.

So Hoffman is useful, not because he overturned realism, but because he demonstrates how easily sweeping claims collapse into conditional ones. And that, in the end, is the real case against reality: not that the world is illusory, but that every theory of the world is hostage to its conditions.