The Child in the Library

Evaluating Einstein's quote on God and atheism.

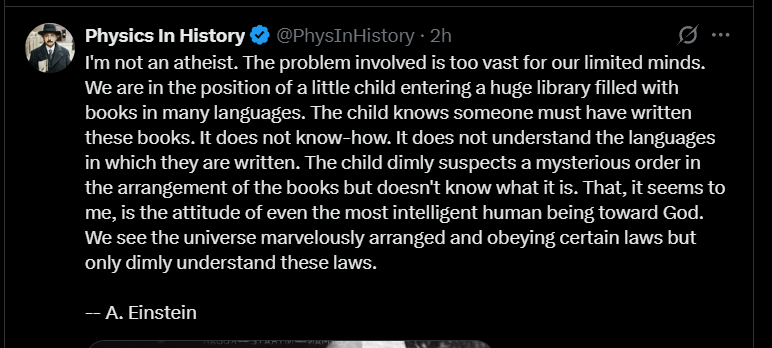

Einstein’s parable about the child entering a vast library is among his most quoted reflections on the divine. It is poetic, disarming, and often misread. What he describes is not faith but humility—a posture of awe toward the intelligibility of the cosmos. Yet it is frequently cited as if it were an argument against atheism. It is not.

The Structure of the Reasoning

Einstein begins with an observation of our cognitive limits: we comprehend only fragments of a universe that seems ordered by laws. To illustrate this asymmetry, he compares humanity to a child who perceives a library full of books in unknown languages. The child does not understand who wrote them, why they exist, or what they mean, but senses that there is meaning. From this, Einstein concludes that the appropriate stance toward reality is reverent curiosity, not denial of the mysterious.

This is a moral attitude, not a syllogism. The parable yields no logical inference from order to agency, nor from ignorance to divinity. The child’s suspicion that “someone must have written the books” is part of the metaphor, not a deduction. Libraries have authors by definition; universes do not.

The Ambiguity of God

Einstein’s “God” is not the personal deity of Abrahamic tradition but a Spinozan abstraction: Deus sive Natura—God, or Nature. In this sense, “God” is simply the total lawful structure of existence. When Einstein says he is “not an atheist,” he means he does not deny that structure or its wonder, not that he believes in a conscious creator. His God neither commands nor judges; it is the invariant order physics attempts to describe.

Thus, the statement is ambiguous because it redefines the theological term while appearing to affirm it. It is a rhetorical reconciliation between scientific humility and cultural language, not a metaphysical claim. A strict atheist could affirm every word of it while rejecting its terminology.

The Philosophical Evaluation

Taken literally, the argument commits a category mistake: it analogizes the universe to an authored text, then infers an author. But the presence of lawlike regularities does not entail lawgivers any more than the existence of geometry entails a geometer. Physics explains order through symmetry, invariance, and conservation, not decree.

Where the passage succeeds is existentially, not logically. It expresses the correct epistemic stance: wonder without superstition, ignorance without nihilism. Its error lies only in the metaphor’s anthropocentric residue. The cosmos is not a library written for us; it is a system within which minds arose capable of reading small portions of its code.

The Verdict

Einstein’s reasoning is not an argument against atheism—it dissolves the dispute. By redefining “God” as the lawful order of nature, he turns theism into naturalism with better poetry. The atheist who replaces “God” with “reality” or “law” can agree entirely. What remains is not belief but reverence: a scientific spirituality grounded in recognition of our limits and the coherence of the world.