The Colonization of Engineering

How Ideology Displaces Method in the Name of Decolonization

Engineering is often misunderstood as a cultural artifact, a tradition that emerged in the West and therefore carries Western assumptions. This framing has become increasingly common in attempts to “decolonize” the discipline. But engineering is not a narrative or a worldview. It is a method for generating reliable predictions about the behavior of physical systems. Its authority comes from one criterion and one criterion only: a model is good if it predicts, and bad if it fails. This epistemic backbone is what allows engineering to scale across cultures, languages, histories, and political systems. It is what makes bridges stand, reactors operate, circuits compute, aircraft remain in the sky, and water treatment plants deliver clean water.

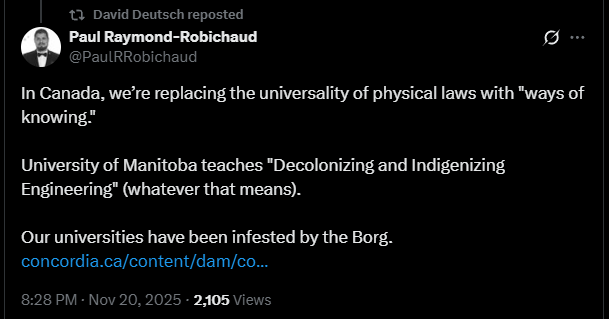

When a curriculum reframes engineering as a cultural practice among other practices, it risks dissolving the very structure that makes engineering universally effective. The “Decolonizing and Indigenizing Engineering” course described in Paul Raymond-Robichaud’s tweet does exactly this. It treats engineering as a culturally situated worldview, collapses the distinction between empirical method and narrative tradition, and replaces predictive rigor with reflective exercises. The result is not inclusion; it is epistemic drift.

1. What Engineering Actually Is

Engineering operates by linking abstract models to physical consequences through a suite of cognitive tools: quantification of variables, systematic modeling of constraints, optimization under competing objectives, iterative testing, and falsifiability. These techniques are culturally agnostic because they are anchored in reality’s invariances. Newton’s laws, Kirchhoff’s laws, the Navier–Stokes equations, and thermodynamic principles do not depend on the worldview of the engineer applying them. The universal predictive power of these tools is what allows engineering to serve humanity across political, cultural, and historical differences. To mischaracterize engineering as a “Western way of knowing” is to confuse its historical origin with its epistemic structure. The method is universal not because the West imposed it, but because reality enforces it.

2. The Central Category Error: Verification vs. Meaning

The course places engineering and Indigenous knowledge traditions on the same epistemic plane, treating them as parallel ways of knowing that deserve equal space in the engineering classroom. This posture aims at respect but commits a fundamental category error. Engineering evaluates claims by verifying whether they correspond to outcomes in the physical world, while Indigenous knowledge evaluates claims by their meaning within a cultural, historical, or relational context. These are not interchangeable standards. Meaning explains significance; verification explains behavior. Both matter, but they answer different questions. A curriculum that collapses these domains deprives engineering of its essential evaluative framework: the capacity to distinguish true predictions from false ones.

3. Reflection Replacing Competence

The course’s assessment model is revealing. It relies entirely on reflective writing, participation in discussions and rituals, and a summative reflective project. There is no modeling, no design exercise, no analysis of physical systems, no testing of hypotheses, and no engagement with constraints. Reflection is meaningful in ethics and in understanding the human impact of engineering, but it cannot substitute for the cognitive architecture required to produce reliable designs. This is not integration. It is skill displacement — replacing competencies essential to engineering practice with introspection and narrative processing. An engineer who reflects well but designs poorly is not an engineer.

4. Agency in the Axio Framework

Axio conceives agency as the ability to construct, evaluate, and choose among models that shape one’s interaction with reality. Engineering is among the most agency-amplifying domains humans have created because it gives individuals and communities the power to predict and alter physical systems. But agency depends on epistemic clarity: the ability to test assumptions, the freedom to reject unfounded narratives, and the discipline to privilege models that work over models that merely feel meaningful. When a curriculum prescribes interpretive frames rather than teaching students how to evaluate and choose among them, it constrains agency instead of expanding it. Replacing engineered models with worldview relativism is not empowerment. It is epistemic enclosure.

5. Respect Without Relativism

None of this critique dismisses the importance of Indigenous history, treaty obligations, environmental stewardship, or culturally informed engagement. These are essential components of responsible engineering practice, and engineers must understand the contexts in which their designs operate. But respect for cultural knowledge does not require flattening epistemic distinctions. It does not require treating empirical success as culturally contingent. And it certainly does not require adopting rituals or belief structures as part of professional training. We can value Indigenous perspectives in environmental stewardship or community engagement without reframing engineering as a cultural narrative. The difference is between learning from another culture and substituting one epistemic foundation for another.

6. What Coherent Integration Would Actually Look Like

A responsible engineering curriculum could integrate Indigenous perspectives without sacrificing method by grounding that integration in historical relevance, empirical clarity, and technical rigor. Teaching the history of engineering projects and their impacts on Indigenous communities would illuminate past harms and prepare students for more responsible practice. Analyzing cases where disregard for Indigenous knowledge caused environmental or social damage would sharpen ethical awareness without diluting technical standards. Incorporating ecological insights that have predictive value would strengthen modeling in fields such as water management or environmental engineering. Embedding thoughtful consultation and consent processes would ensure that engineering projects respect community autonomy while preserving engineering’s methodological backbone. This approach enriches engineering practice without weakening its epistemic commitments.

Conclusion: Preserving the Epistemic Spine

Engineering’s strength is its indifference to story. It cares only about whether a model corresponds to reality. When truth becomes negotiable, safety becomes negotiable. When predictive rigor is replaced by narrative alignment, the discipline loses the feature that makes it indispensable. A reconciled engineering pedagogy should integrate context, history, and community insight — but never at the cost of epistemic integrity.

Respect the culture. Learn the history. Engage the community. But keep engineering anchored to truth.