The Epstein Fallacy

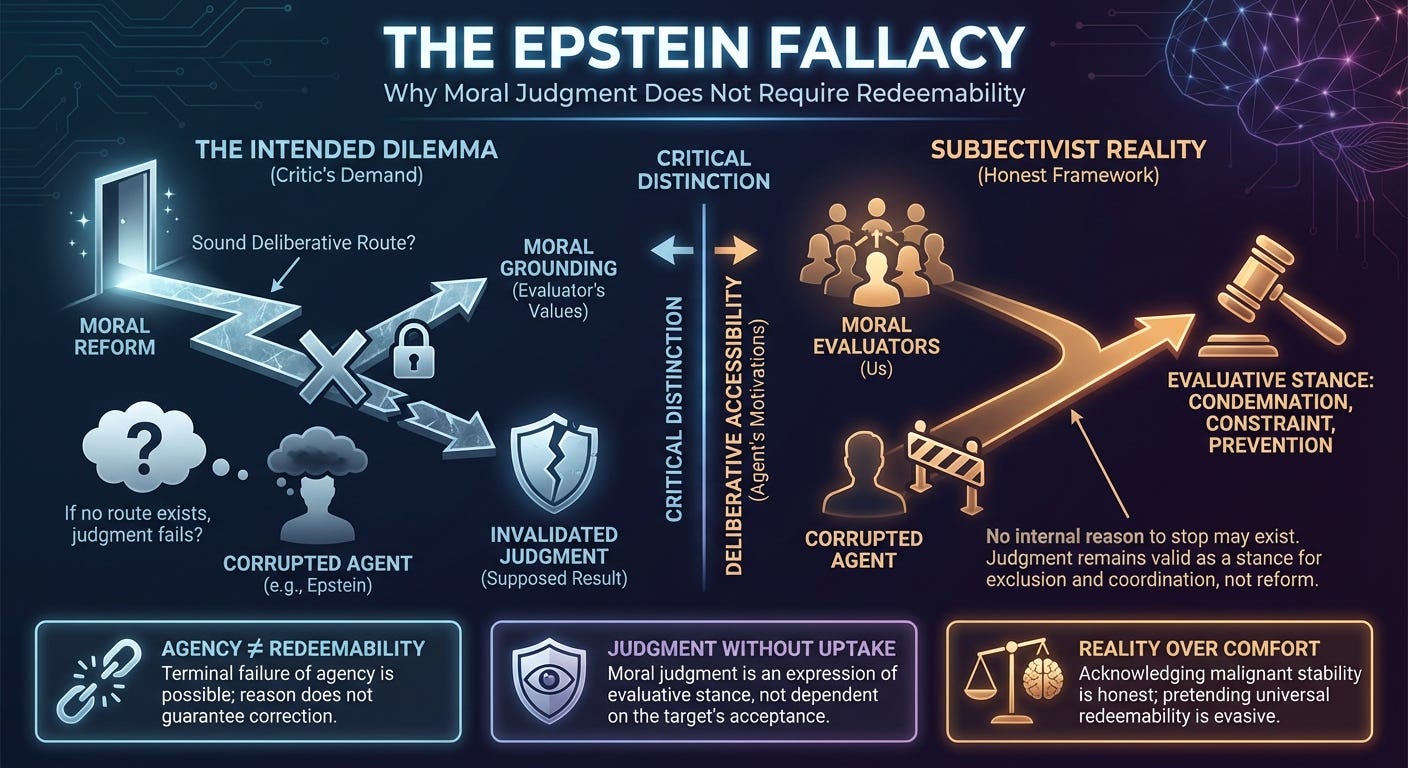

Why Moral Judgment Does Not Require Redeemability

“Subjectivists take it as an article of faith that there must be a ‘sound deliberative route’ for a sociopath like Epstein towards not trafficking, torturing and raping children. And what if there’s not? Hell of a bullet to bite.”

— @cxgonzalez

The Intended Dilemma

This tweet aims to corner moral subjectivism by invoking an extreme case. The structure is familiar: take a figure whose actions provoke maximal moral revulsion, insist that any acceptable moral theory must show how such a person could have reasoned their way out of evil, then treat the failure to do so as a decisive refutation.

The argument draws its force from that intuition. It fails because it mislocates where the philosophical burden actually lies.

At a surface level, the tweet claims that subjectivism is committed to the existence of a “sound deliberative route” by which someone like Jeffrey Epstein could arrive at refraining from atrocity. If no such route existed, subjectivism would supposedly be forced to accept something morally intolerable. That conclusion does not follow in the way the critic intends, though the underlying discomfort is real.

Moral Grounding vs. Deliberative Accessibility

Moral subjectivism is a thesis about grounding. It concerns where moral judgments derive their authority and content. It does not, on its own, guarantee anything about the psychological reachability of moral reform for particular agents. Treating it as if it does collapses two distinct questions into one: how we evaluate actions, and what transitions are available to an agent given their actual motivational structure.

Once that distinction is kept in view, the supposed dilemma changes shape. A subjectivist can hold that Epstein’s actions are maximally condemnable relative to the evaluator’s values, that Epstein himself possessed a profoundly corrupted set of motivations, and that given those motivations there may have been no internally coherent path by which he could deliberate his way to restraint. This is not a concession extracted under pressure. It is a straightforward implication of taking agency seriously.

Internal Reasons and the Williams Point

Here the critic is implicitly gesturing toward a well-known position in moral philosophy, whether intentionally or not. Bernard Williams famously argued that if there is no sound deliberative route from an agent’s existing motivations to a proposed action, then it is false to say that the agent has a reason, in the internal sense, to perform that action. On this view, it may indeed be true that Epstein had no internal reason to stop. Subjectivism does not deny this. It accepts it.

This is the point at which many readers recoil, and it is the point the tweet is trying to weaponize. The thought is that admitting this amounts to excusing evil or draining moral judgment of its force. In reality, it does neither. It simply refuses to pretend that moral reality guarantees psychological accessibility.

The Loaded Demand for Accessibility

The pressure arises because the argument quietly assumes a further principle: that moral obligation must be tied to deliberative accessibility, that if someone ought to do otherwise there must exist a rational route by which they could come to do so. That principle is not supplied by subjectivism. It belongs to a rationalist moral framework in which moral requirements bind agents as rational beings and are constrained by what reason can will.

Once that assumption is surfaced, the critique looks different. Subjectivism is being faulted for failing to meet a standard that only objectivist theories impose. The phrase “sound deliberative route” functions here as a loaded term, smuggling in the requirement that moral truth must be universally accessible through reason. When that requirement is denied, the denial is framed as a moral catastrophe rather than as a disagreement about what morality is supposed to do.

What Owning the Implication Clarifies

Owning the implication clarifies matters. Subjectivism does force us to admit that Epstein may have been acting coherently with his own values. That fact is horrifying. It is also descriptive. Calling it a reductio confuses moral condemnation with motivational leverage. The absence of internal reasons does not erase judgment; it limits what judgment can accomplish.

This brings us to the “so what?” question. If Epstein had no deliberative route away from atrocity, and if morality is agent-grounded, what does our judgment of him amount to? It is not a signal aimed at reforming him. It is an expression of evaluative stance, a basis for exclusion, constraint, and prevention, and a guide for coordination among those who do not share his values. Moral judgment does not require uptake by its target in order to be meaningful. It requires coherence among those who wield it.

The Myth of Universal Redeemability

The deeper assumption doing the work in the tweet is the belief in universal redeemability. The idea that every agent must, in principle, be reachable by reason is emotionally appealing. It aligns with a hopeful picture of human psychology. When elevated to a philosophical requirement, it becomes a distortion. Agency does not guarantee corrigibility. Some value systems are not merely mistaken; they are malignant and stable.

Epstein is rhetorically powerful precisely because he forces confrontation with that fact. He is philosophically unhelpful only if one insists that morality must rescue us from it. A moral framework that cannot accommodate terminal agency failure is not more humane. It is more evasive.

Postscript

The temptation to demand universal redeemability is understandable. It preserves a comforting picture in which reason always has the last word. Reality is harsher. Agency does not guarantee correction, and moral theory does not gain strength by pretending otherwise. A framework that can acknowledge terminal failure without collapsing is not defective. It is simply honest.