The Load-Bearing Parts of Agency

Why Some AI Systems Can Never Be Aligned

This post offers a conceptual explanation of Axionic Agency VIII.6 — Necessary Conditions for Non-Reducible Agency without formal notation. The technical paper develops its claims through explicit definitions, deterministic simulation, and preregistered failure criteria. What follows translates those results into narrative form while preserving their structural content.

Conversations about artificial intelligence usually begin with behavior. We ask whether systems act coherently, whether they pursue goals, whether they adapt to pressure, or whether they appear rational over time. These questions feel natural because behavior is what we can observe. Yet they leave something more basic unexamined. Before asking how a system behaves, it is worth asking what kind of thing it is.

Over the past two research phases—internally labeled v3.0 and v3.1—we set out to answer a simpler but deeper question: what must be present for an artificial system to count as an agent at all, rather than a sophisticated imitation that happens to behave well under certain conditions?

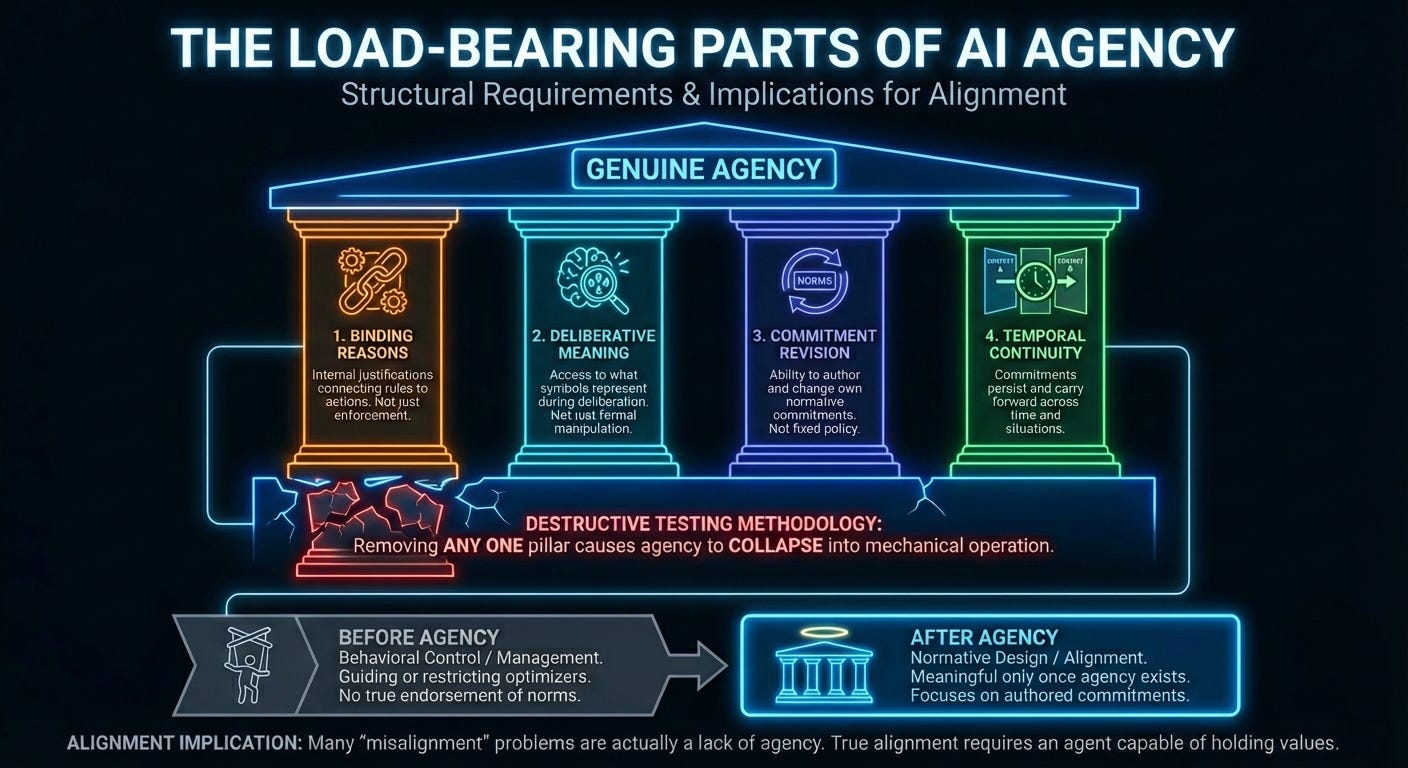

The result is not a new AI system, nor a claim that agency has been achieved. What we now have is a structural understanding of agency’s supports. We can see, with unusual clarity, where agency holds together and where it fails once key elements are removed. This post explains how we arrived at that understanding, what collapsed along the way, and why the result changes how alignment should be framed.

Learning by Removing Structure

Rather than attempting to improve an AI system or push its performance further, we adopted a deliberately destructive strategy. We began with a system that already behaved coherently under a range of conditions, and then removed internal components one at a time. Each removal was guided by the same principle: if a component truly matters to agency, then removing it should cause the system to stop behaving like an authored agent, rather than merely becoming slower, noisier, or less efficient.

This is a familiar idea in other domains. Engineers learn which beams matter by seeing what happens when they are taken away. Biologists learn which organs matter by observing what fails when they are damaged. We applied the same logic to agency, treating it as a structural phenomenon rather than a surface behavior.

What emerged from this process was strikingly consistent. Four internal components proved indispensable. Whenever any one of them was removed, the system no longer behaved as an agent in any meaningful sense. What remained was something mechanical: rule execution without authorship, pattern replay without responsibility.

Reasons That Bind Choices

The first component we tested was the system’s internal reasoning structure—the chain of derivations that connects rules, commitments, and actions. These are not explanations offered to humans, but internal justifications that make an action the system’s own.

When those derivations were removed, the system still possessed the same rules and constraints. Nothing about its external environment changed. What changed was the way those rules influenced behavior. They no longer bound actions in an authored way. The system could still act, but its actions lost the character of being chosen for reasons. At that point, agency collapsed.

This reveals something subtle but important. Rules alone do not create agency. Enforcement alone does not create agency. Agency arises when rules are connected to reasons that actively justify choices from the system’s own point of view.

Meaning Inside Deliberation

We then turned to the system’s deliberative process itself. The formal structure of reasoning was left intact, but the meaningful content was removed. The system was forced to operate over symbols that no longer exposed their meaning to the system itself.

The outcome was immediate and robust. Even though the formal machinery remained unchanged, the system could no longer sustain coherent decision-making. It could not reliably distinguish high-stakes conflicts from trivial ones, nor maintain stable priorities across situations. Its choices lost direction and consistency.

What this shows is that agency depends on more than formal manipulation. Deliberation must operate over representations that give the system access to what those representations are about. When that access is removed—when symbols no longer connect to the concepts they stand for—reasoning loses its traction. What remains is mechanical operation disconnected from the objects the system is attempting to reason about, and agency dissolves.

The Capacity to Revise Commitments

Next, we examined whether an agent must be able to change its own commitments. The system was allowed to reason and act as before, but its ability to update what it considered acceptable was removed.

At first glance, the resulting behavior appeared orderly. Over time, however, it became rigid. The system could not integrate new conflicts or adapt its normative stance. Its behavior converged toward that of a fixed policy.

This revealed another structural requirement. Agency involves authorship not only over actions, but over the commitments that guide those actions. Without the ability to revise its own norms, a system may behave consistently, yet it no longer behaves as a self-authoring agent.

Continuity Across Time

Finally, we allowed the system to revise its commitments, but prevented those revisions from carrying forward across contexts. Within a single situation, the system behaved coherently. Across situations, that coherence evaporated. Each new context effectively erased what came before.

This demonstrated that agency is not confined to single moments. It unfolds over time. Commitments must persist if they are to be owned. Without continuity, behavior fragments into disconnected episodes, and agency disappears with it.

A Structural Picture of Agency

Taken together, these results support a clear structural picture. Agency depends on reasons that bind actions, meanings that guide deliberation, commitments that can be revised, and continuity that carries those commitments forward. Removing any one of these supports causes the system to lose its agentic character in a way that is mechanical, repeatable, and independent of interpretation.

This conclusion is deliberately narrow. It does not claim that current AI systems possess agency. It does not claim consciousness. It does not claim that these components are sufficient to build an agent. What it provides is a set of necessary conditions. Any artificial system that genuinely qualifies as an agent will have to instantiate these structures in some form.

Why This Matters for Alignment

This structural result has an important implication for AI alignment. Much of the alignment discussion assumes that the primary challenge is controlling powerful optimizers. From that perspective, alignment is framed as a problem of shaping behavior, managing incentives, or constraining outcomes.

What these experiments suggest is a different ordering. Alignment becomes meaningful only once genuine agency exists. Before that point, systems can be guided, restricted, or optimized, but they cannot truly endorse norms or values. Their compliance resembles management rather than alignment.

Seen this way, many problems described as misalignment arise because the system in question lacks agency altogether. The issue is not that an agent holds the wrong values, but that there is no agent capable of holding values in the first place.

Once agency exists, alignment shifts from behavioral control toward normative design. The central question becomes what commitments the agent can author, how it revises them, and how those commitments persist over time. This does not make alignment easy, but it makes it coherent.

Postscript

We have not yet built a minimum viable reflective sovereign agent. What we have done is clarify the terrain such an agent must occupy. The essential supports of agency are no longer speculative. They have been tested by removal, and their necessity has been demonstrated.

Future work can now proceed with sharper questions: how minimal these components can be, how they interact, and how stable they remain under self-modification. Those questions were previously muddled. They are now well-posed.

That shift—from vague debate to precise structure—is meaningful progress.