The National Interest Fallacy

How a category error became the most powerful justification for harm

“The ‘realist’ view of international affairs is false. People don’t, and can’t, act in their interests because they don’t know what those are until they have a world view.”

— David Deutsch

The illusion of necessity

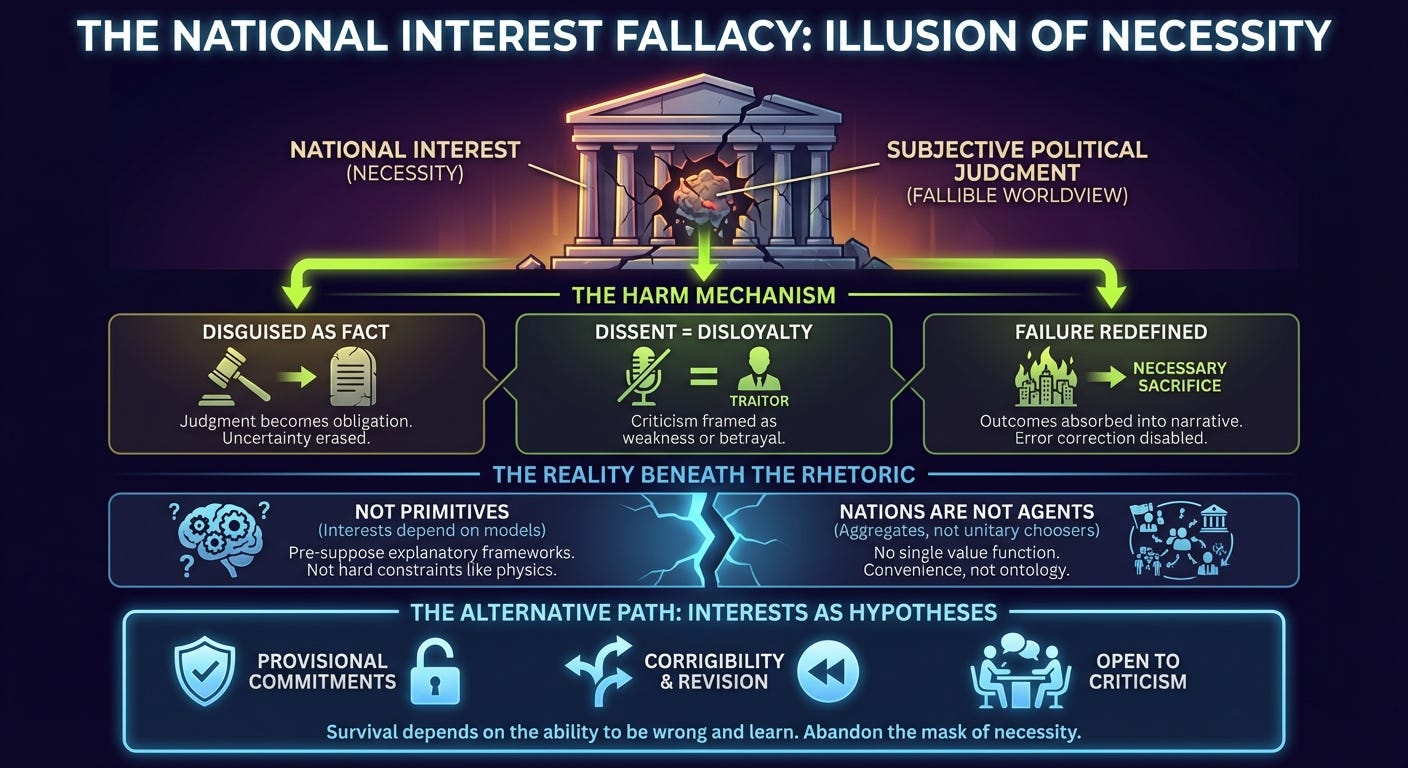

Few phrases in politics carry as much moral authority while concealing as much conceptual confusion as national interest. It appears in speeches just before wars begin, in memoranda authorizing surveillance, in arguments for secrecy, sacrifice, and coercion. It is spoken with the cadence of inevitability, as though it names a hard constraint imposed by reality itself.

That cadence is doing almost all the work.

The phrase does not describe a fact about the world. It describes a belief about the world—one that has been rhetorically upgraded from judgment to necessity. The danger lies not only in the policies justified by national interest, but in how the concept disables the very mechanisms that could reveal those policies to be mistaken.

To see this clearly, we have to move upstream, to the concept of interest itself.

Interests are not primitives

An interest is not a basic feature of reality. It does not exist prior to explanation, waiting to be discovered by sufficiently rational actors. To say that an action is “in one’s interest” already presupposes an explanatory framework: a model of how the world works, a theory of causation, an evaluation of outcomes, an assessment of risk, and a choice of time horizon. Without such a framework, the claim has no determinate meaning. With a false framework, it acquires dangerous meaning.

This is the force of Deutsch’s claim. Actors do not generally fail because they irrationally pursue their interests. They fail because they misidentify what their interests even are, and that misidentification flows directly from the worldviews that generate them.

Acknowledging this does not require denying hard constraints. Annihilation is incompatible with continued agency. Suffocation is incompatible with life. There are physical and biological limits that no worldview can negotiate away. But constraints are not interests. They rule out futures without selecting among the remaining ones. The moment a society moves from “we cannot survive this” to “therefore we must do that,” it has crossed from physics into interpretation—and interpretation is fallible.

Once this distinction is made, the appeal to national interest begins to unravel.

Nations are not agents

Even if interests were objective facts, nations would still be the wrong kind of thing to possess them.

A nation has no unified belief state, no single value function, no shared vantage from which futures are evaluated. It is an aggregate pattern composed of individuals, institutions, incentives, traditions, and power relations, all of which evolve asynchronously and often in conflict. Treating such a pattern as a coherent chooser is, at best, an analytical convenience.

The phrase national interest silently converts that convenience into ontology. It treats a loose, historically contingent aggregate as though it were a unitary agent with stable preferences. In doing so, it erases individual agency while presenting the result as collective rationality.

This critique is not aimed at realism as a descriptive shorthand used by historians or analysts. Simplified models can be useful. It is aimed at the elevation of “national interest” from analytical device to justificatory principle—where uncertainty may be acknowledged rhetorically but is erased operationally, and judgment is enforced as necessity.

That elevation is what gives the concept its political potency.

How the fallacy licenses harm

When an action is justified by national interest, it is no longer presented as a hypothesis about the future. It is presented as a requirement. Disagreement ceases to be epistemic and becomes moralized. Dissent is reframed as disloyalty, weakness, or betrayal.

At the same time, the claim becomes functionally unfalsifiable. If a policy justified by national interest produces disaster, the outcome is not treated as evidence against the underlying judgment. It is absorbed into the narrative as unavoidable sacrifice, insufficient resolve, or a necessary cost on the path to eventual security. The concept protects itself by redefining failure.

Once this structure is in place, coercion ceases to be a regrettable last resort. It becomes a duty. Individuals are no longer agents whose judgments matter, but instruments whose compliance is required. Extreme harm no longer requires pathological actors; it requires only ordinary officials operating within a framework that has reclassified choice as necessity.

Catastrophe as epistemic failure

The historical record reflects this pattern with disturbing regularity. The most destructive regimes of the twentieth century did not collapse because they were insufficiently committed to their interests. They collapsed because they enforced false explanatory models, suppressed dissent, and thereby froze their own capacity for error correction.

Once disagreement is criminalized and alternative models are excluded, rationality does not save a system. It accelerates its descent. Policy becomes more coherent, more optimized, and more catastrophic precisely because the underlying model is wrong and cannot be challenged.

This is why appeals to national interest are so often accompanied by censorship, propaganda, and punishment for dissent. These are not accidental excesses. They are symptoms of epistemic weakness.

Decision under uncertainty

None of this implies that political decisions can be deferred indefinitely, or that leaders must wait for consensus before acting. Decisions often must be made under severe time pressure and genuine uncertainty. But acting under uncertainty does not require pretending uncertainty has vanished.

Science, engineering, and medicine all operate this way. Planes fly before theories are complete. Treatments are administered without certainty. What distinguishes successful action under uncertainty from catastrophic action is not hesitation, but corrigibility. Decisions can be made rapidly while remaining open to revision. The danger is not commitment; it is commitment that cannot be criticized, reversed, or learned from.

The language of national interest undermines precisely this capacity. By framing judgment as necessity, it converts provisional commitments into dogma.

Interests as hypotheses, not mandates

Viewed through the lens of uncertainty, political action is always an attempt to shape a distribution of possible futures without knowing which will occur. No individual and no collective has access to the full space of futures or their relative likelihoods. Claims of national interest pretend to solve this problem by collapsing uncertainty prematurely and enforcing a single narrative about which futures count.

The harm lies not only in the outcomes that are realized, but in the alternative futures that are forcibly prevented from being explored.

The only defensible way to speak about interests—political or otherwise—is as conjectures rather than commands. Interests are hypotheses generated by fallible models. They must remain contestable, revisable, and exposed to criticism. The moment they are enforced as objective necessities, agency collapses and catastrophe becomes a matter of time rather than chance.

Postscript

There are no national interests in the sense political rhetoric requires. There are only individual agents embedded in uncertain worlds, acting under imperfect models, whose survival depends on their ability to be wrong and to learn.

“National interest” persists because it is rhetorically useful. It converts judgment into obligation and disagreement into disloyalty. But its historical function has not been to guide societies wisely. It has been to disable error correction at scale.

Abandoning it does not require passivity or indecision. It requires leaders willing to say, openly and repeatedly: this is our best current judgment, not our destiny—and to remain answerable when that judgment proves wrong.

That is why some of the worst acts in history are justified in its name—and why they will continue to be, as long as the fallacy goes unchallenged.