The Nature of Beliefs

Beliefs as models of agent behavior

1. Beliefs as Behavioral Models

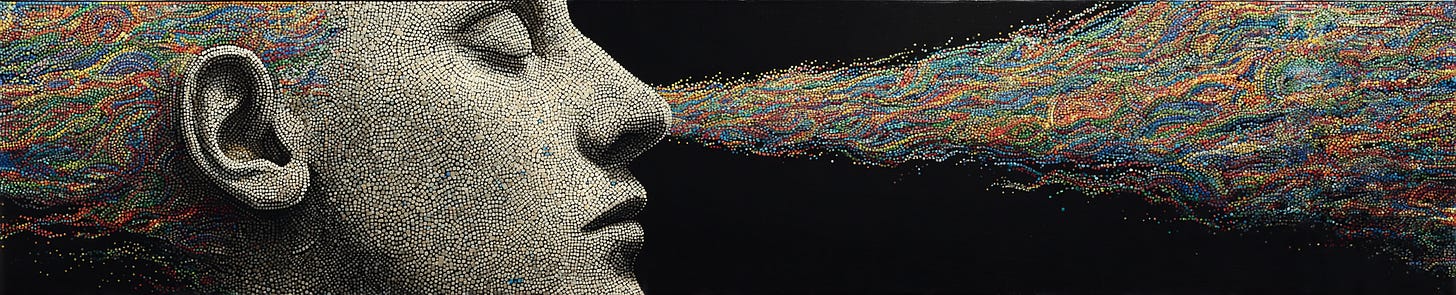

Beliefs are not static propositions stored inside minds. They are models of regularity, evolved and learned to explain and predict behavior—first our own, then that of others. To believe that a bridge will hold is to model it as structurally reliable, and thus to walk across. To believe that someone is honest is to model their future actions as aligned with truth. Belief, in this view, is not representational content but functional compression: a simplified generative model that guides behavior under uncertainty.

In predictive-processing terms, a belief is a prior: a probability distribution over possible world-states, continuously updated by sensory evidence. In Dennett’s language, it is a feature of the intentional stance: an attribution that makes the behavior of an agent intelligible and predictable.

2. Beliefs as Properties of Models of Agents

Beliefs exist only within models of agents, never in the agents themselves. A physical or computational agent merely enacts processes—it perceives, reacts, and regulates. But when we construct a model of that agent as an intentional system, belief becomes a meaningful term. It appears only within the representational layer that describes how an agent relates to its environment and to itself.

This applies even internally. An agent can maintain a self-model that depicts itself as an agent—and that self-model can contain beliefs. But the beliefs exist only within that model, not in the agent as a physical entity. The same rule applies recursively: models of agents can contain models of agents, each level ascribing beliefs to the one beneath it.

Belief is a model of the world inside a model of an agent.

Agents don’t have beliefs; models of agents do.

This framing unifies the two perspectives: beliefs as behavioral models, and beliefs as properties of models of agents. They describe the same phenomenon from different vantage points—from within the self-model (guiding action) and from without (explaining action).

3. Belief and Calibration

A belief’s epistemic virtue lies not in its truth value but in its calibration—how well its predictions survive contact with reality. Confidence is the expected stability of a belief under new evidence; faith is confidence that refuses calibration. Beliefs are living hypotheses, not frozen propositions. Their function is to reduce surprise, not to defend identity.

4. The Recursive Stack of Interpretation

Belief exists at multiple interpretive layers:

World: causal dynamics, devoid of representation.

Agent: processes and control systems, but no beliefs in themselves.

Model of Agent: beliefs appear here—in representations of how the agent perceives, values, and predicts.

Model of Self: an agent’s internal model of itself as an agent, which therefore contains beliefs.

Observer: a model of another agent’s self-model, attributing beliefs for explanation.

Beliefs, then, arise only in the modeling relation itself—they are features of how systems represent agents, not how agents exist in the world.

5. Toward a Unified Theory of Belief

To believe is to model. To explain belief is to model a model. This recursive architecture underlies all cognition, communication, and social inference. It is how agents synchronize their internal models through language, imitation, and theory of mind.

Beliefs are not containers of truth but constructors of coherence. They bind perception, action, and interpretation into a single predictive loop. What makes a belief valuable is not whether it is correct in some metaphysical sense, but whether it reduces error without freezing adaptation.

Belief is the modeling function of mind: the bridge between prediction and understanding.