The Tail That Wags the Dog

Why so many laws are built for the worst-case few

One of the least comfortable truths about governance is that many of the rules you live under are not written for you. They are written for someone else—the small slice of the population whose behavior generates outsized risks, costs, and disruptions. In statistics, they are the tail of the distribution. In civic life, they are the ones who drive policy far more than the median citizen ever will.

From Schoolyard to City Hall

If you attended a public school, you’ve seen the dynamic up close. Entire disciplinary systems can be built around a handful of chronically disruptive students. Teachers enforce rules not because the average kid needs them, but because a few do—and without those rules, the environment can collapse into chaos. This is not a moral judgment; it’s a recognition that maintaining order requires designing for the most likely points of failure.

That pattern scales. At the municipal level, zoning laws often exist in part to keep certain high-risk uses of property away from residential neighborhoods. At the national level, entire swaths of the criminal code, safety regulations, and tax expenditures exist to contain, manage, or offset the costs created by a small minority.

The Tail-Risk Principle

The underlying principle is simple:

In many domains, a small proportion of actors create a disproportionate share of problems.

This is a manifestation of the Pareto distribution, not a conspiracy.

Because the harm they can cause is non-trivial, the system calibrates itself to contain them.

You see it in public safety law: seat belt requirements, fire codes, and drunk driving laws are enforced universally because a few people will otherwise take risks that endanger many.

You see it in public finance: social safety nets exist because some portion of the population will fall into chronic need.

The Oversimplification Trap

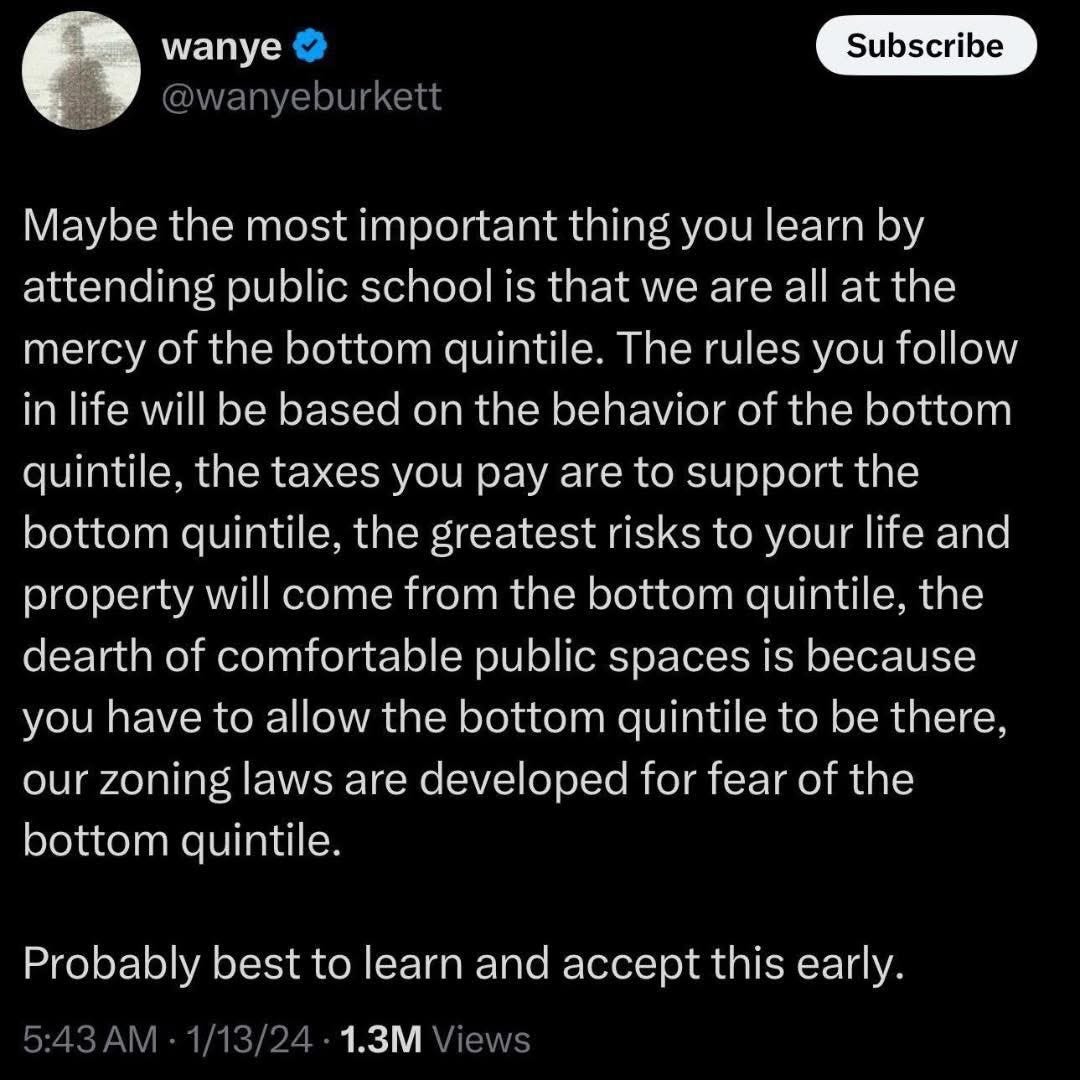

Where this gets distorted is in the rhetoric. A popular cynical framing—like the viral “bottom quintile” tweet—claims that all of society’s costs and restrictions are due to the lowest-performing 20%. It’s rhetorically potent because it compresses a complicated dynamic into a single villain. But it’s not accurate.

First, the “bottom quintile” is not a monolith. Most people in it cause no unusual burden; some people far above it cause enormous harm (white-collar crime, political corruption, environmental destruction).

Second, some constraints exist for reasons unrelated to bad actors—like coordination problems, shared infrastructure, and universal public goods.

The Other Tail

If you want a fuller picture, you have to look at the top tail as well.

Elite-driven crises—financial collapses, corporate fraud, large-scale environmental damage—often impose costs far exceeding those caused by street-level crime or petty disorder. The regulations that follow in their wake can be just as restrictive and expensive, and they apply to everyone.

In other words, the tail that wags the dog comes in more than one shape. Policy often evolves in response to the extremes at both ends of the spectrum.

The Policy Trade-Off

The real civic question is not whether we should design for the tail. We have to—it’s built into the math of risk. The question is how much we are willing to let the behavior of the least compliant set the rules for the rest of us, and at what cost to freedom, efficiency, and shared space.

Understanding this early changes the way you read the news, vote, or react to yet another set of safety instructions on a product you’d never misuse. It explains why politics can feel like it’s built for “someone else’s problems” and why debates over regulation so often boil down to the age-old dilemma:

Should we all be governed by the worst among us, or should we accept more risk to give the rest more room to breathe?