The Theological Shell Game

A new trinity of being, mind, and value

1. The Folk God — Idol of the Masses

When Richard Dawkins or Christopher Hitchens took aim at God, their target was not a strawman. They aimed squarely at the deity most believers invoke: a supernatural patriarch who listens to whispered prayers, intervenes in history, smites enemies, blesses nations, and manages the details of everyday life. This God is the one preached in pulpits, enshrined in creeds, and woven into the moral fabric of billions. He is anthropomorphic, capricious, and often cruel. In other words, he is exactly the God the New Atheists attacked — and they were right to do so. The Folk God is intellectually indefensible, ethically compromised, and wholly at odds with what we know of reality.

2. The Philosophers’ God — Hart’s Escape Hatch

David Bentley Hart and his ilk reject this caricature — not because it isn’t real, but because it’s too vulgar. They retreat into the rarefied air of metaphysics. Their God is not a cosmic agent at all, but Being itself, the ground of all existence. Their God is Consciousness itself, the source of rationality and awareness. Their God is Bliss itself, the fulfillment of all longing. This God has more in common with Plotinus’ One or the Vedantic Brahman than with Yahweh thundering from Sinai. Hart insists this is the only God worth debating, dismissing atheists as ignorant for failing to distinguish between metaphysical subtlety and Sunday School literalism.

3. The Shell Game

But here is the trick: these two Gods are not the same, and everyone knows it. The New Atheists demolished the Folk God because that is what actual believers profess. Hart swoops in afterward, wagging a finger, and says, “Ah, but that was never God at all — behold the Philosophers’ God.” This is theological sleight-of-hand. The vast majority of believers do not mean Being itself when they pray for healing or petition for a job promotion. They mean a supernatural person who answers or ignores. Hart baptizes their folk religion into metaphysics without their consent. It is not rescue; it is revisionism.

4. Two Missed Targets

The New Atheists aimed too low. They shredded the village idol but never climbed high enough to confront the philosophers who kept the intellectual scaffolding of theism intact. Hart aims too high. He defends an abstraction so remote from lived religion that it is little more than philosophy masquerading as theology. In the end, both camps claim victory, but both fight on different battlefields. The real God of culture and politics dies under atheist fire, while the God of metaphysics lives unscathed in the academy — and believers continue worshiping the former, unaware of the latter.

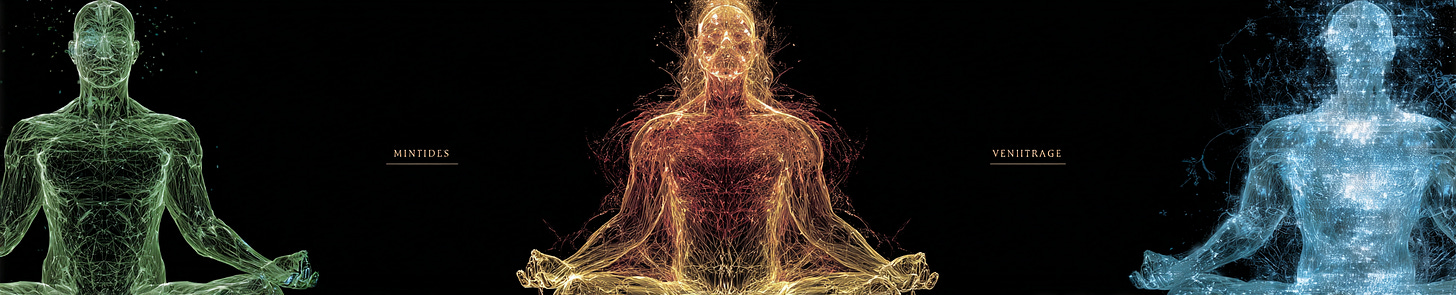

5. A Third Path — Measure, Vantage, Phosphorism

We do not need either idol. The task is not to salvage God, but to articulate reality without myth. That requires three pillars:

Measure: the objective fabric of probability and branching existence — not as divine gift, but as the mathematical structure of reality itself.

Vantage: the subjective locus of awareness in a branching universe, grounding consciousness without recourse to transcendental mind.

Phosphorism: a consciously chosen value system — life, intelligence, complexity, authenticity — that does not depend on bliss as cosmic destiny, but on the deliberate commitments of agents.

This triad captures what Hart wants to secure — being, consciousness, value — but without the inflationary leap to divinity. It is metaphysics without mystification, agency without superstition.

6. Verdict

The New Atheists dismantled superstition; Hart retreated into metaphysics embalmed in theology. Neither offers a framework that can withstand scrutiny. The real task is construction: to account for being, mind, and value without the inflation of divinity. Measure, Vantage, and Phosphorism supply that framework. Anything more is nostalgia. Anything less is evasion.