The Wound and the Weapon

How Trauma Narratives Heal and Control

Trauma is not simply a wound of the body or brain; it is a fracture in the story one tells about oneself. A coherent psyche depends on continuity — past, present, and future stitched into a legible whole. Trauma rips a hole in that fabric. It leaves a gap in the story where meaning should reside, and into that gap seeps confusion, shame, and silence. The therapeutic impulse — whether in psychoanalysis, narrative therapy, or even everyday friendship — is to help the injured reclaim authorship. To speak the wound aloud is to begin repairing the narrative.

So far, this is humane and true. But once we recognize trauma as a disruption in narrative, a darker corollary follows: narratives are not merely personal. They are social, political, and cultural. They frame who is heard and who is silenced, who is the victim and who is the oppressor, who deserves sympathy and who deserves censure. To invoke trauma is therefore never a neutral act. It shifts the axis of power in a conversation. It redirects the spotlight, reorders the terms of debate, and places the speaker in the privileged role of witness.

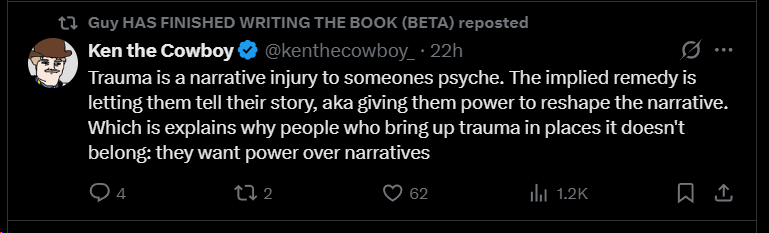

This is the sharp insight behind the claim that those who introduce trauma into irrelevant contexts are not simply over-sharing, but seeking power. By dragging their wound into a space where it does not belong, they tilt the narrative terrain in their favor. The move is not only therapeutic; it is rhetorical. Victimhood becomes a lever.

Yet here the hot take falters. Not every disclosure of trauma is a calculated grab for dominance. To say so is to collapse human motives into a caricature of manipulation. Sometimes trauma bursts forth clumsily because the sufferer has lost their sense of proportion. Sometimes it is desperation for connection. Sometimes it is a maladaptive attempt at self-explanation. Reducing all trauma-talk to narrative power games is as crude as dismissing all illness-talk as attention-seeking. It confuses a real dynamic with a universal law.

The deeper truth is that trauma occupies a double register: healing and power. On one register, the injured seek coherence. They tell their story because they must, because silence corrodes the soul. On the other register, stories shape worlds, and trauma-talk inevitably carries political weight. These registers cannot be separated. They coexist, and to ignore one is to misunderstand the other.

The lesson, then, is not to sneer at trauma as power-play, nor to sanctify it as pure authenticity. It is to recognize the dangerous ambiguity. Trauma narratives heal, but they also sway. They restore agency to the teller, but they can also colonize the collective narrative. The wise response is neither automatic indulgence nor automatic suspicion, but a careful discernment: is this story being told to stitch a soul, or to seize the stage? Often it is both.

And that, perhaps, is the most sobering recognition: in the politics of meaning, wounds are weapons. To understand trauma is to see not only the broken story, but the battlefield upon which it is retold.