Thinking vs. Feeling

Rethinking the Cognition Divide

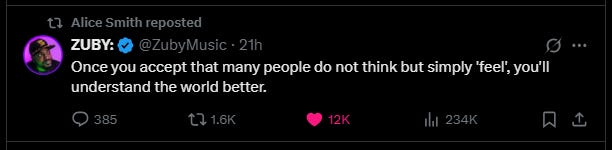

We often see a stark distinction drawn between thinking and feeling. A recent provocative tweet declared: "Once you accept that many people do not think but simply 'feel', you'll understand the world better." While this captures a common insight about human behavior, it's overly simplistic—and misses an important truth about cognition.

Thinking vs. Feeling: A False Dichotomy?

To clarify, let's define terms explicitly:

Thinking refers to deliberative, conscious cognitive activities like reasoning, decision-making, problem-solving, and abstract planning. It involves logical coherence, systematic analysis, and is often slow and explicit.

Feeling involves rapid, automatic emotional evaluations, intuitive judgments, and value-based assessments. Feelings are immediate and visceral, often not consciously controlled or explicitly articulated.

While distinct, both are properly understood as forms of cognition, or information-processing activities of the brain.

Cognition: The Broad Category

Cognition encompasses all mental activities involved in acquiring, processing, and using information. Under this broad umbrella, we include:

Deliberative Cognition (Thinking)

Explicit reasoning

Problem-solving

Conscious reflection

Affective Cognition (Feeling)

Emotional responses

Intuitive appraisals

Rapid value judgments

Both evolved for adaptive purposes, but fulfill different roles:

Thinking allows flexible, strategic responses to complex and novel problems.

Feeling enables rapid, survival-oriented responses, immediately signaling threats or opportunities based on evolutionary importance.

Crucially, thinking and feeling continuously inform each other. Emotions establish priorities and shape decision-making; reasoning modulates emotional impulses and guides deliberate action.

Thinking Beyond Humans

It's important to note thinking is not uniquely human. Many non-human animals demonstrate genuine deliberative cognition:

Tool use in crows and chimpanzees, who creatively solve novel problems.

Planning in squirrels caching food for future needs.

Reasoning in dolphins and dogs that demonstrate inferential logic.

Abstract thinking in parrots and great apes that learn symbols and communicate sophisticated concepts.

Metacognition (awareness of their own cognitive processes) observed in dolphins and monkeys.

Rather than categorically separating humans from animals, it's better to view cognition along a continuum of complexity and abstraction.

Misunderstanding Leads to Conflict

Many misunderstandings arise precisely because people mistake emotional reactions for reasoned deliberation. Recognizing that both are forms of cognition—but serve different purposes—helps us interpret human behavior more clearly. Emotional responses are not "lesser" forms of cognition, simply different.

A more accurate way of expressing the original insight might be:

"Once you understand that many people's cognition is primarily affective rather than deliberative, you'll better grasp human behavior."

Conclusion

Thinking and feeling are distinct but complementary cognitive processes. Appreciating their differences and interdependencies—and acknowledging the cognitive continuity between humans and other animals—provides clearer insight into the complexity of minds, human and non-human alike.