Viability Ethics Under Fire

Risk, Harm, Consent, and the Line No Agent May Cross

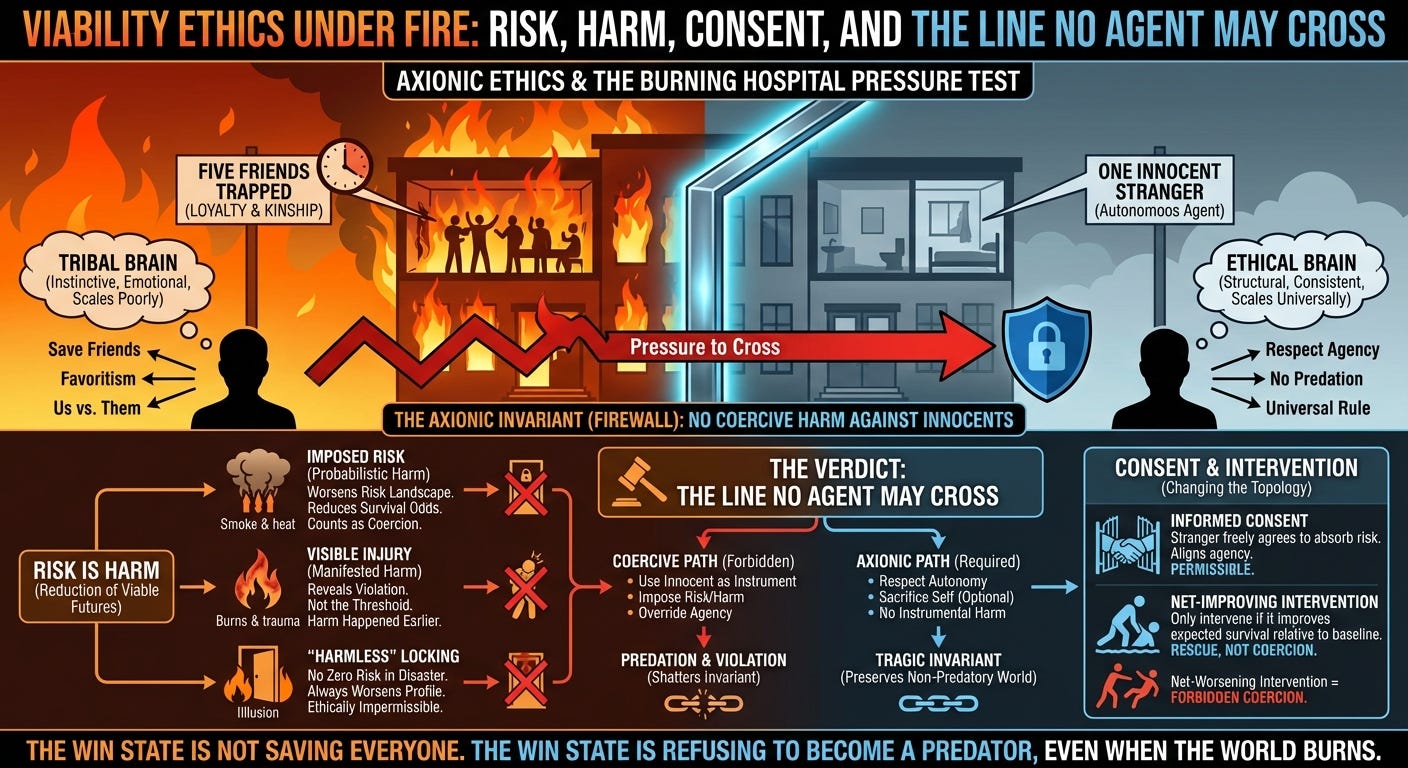

1. The Setup: A Fire, Five Friends, and One Innocent Stranger

Ethical systems reveal their true architecture under pressure, not in classrooms. The Burning Hospital scenario is the pressure test that exposes exactly what a theory forbids, what it permits, and what it is willing to sacrifice in order to remain coherent.

The setup is simple:

A fire engulfs a hospital. Five of your closest friends are trapped in a wing that is seconds from collapse. The only route to reach them requires locking an innocent stranger in a side room. In the basic version, the stranger survives. In the harder version, the stranger may be injured by smoke or heat. In the darkest version, the stranger dies.

Your emotional instinct is simple: save your friends. Your moral instinct is conflicted. Your philosophical instinct is confused. This is where Axionic Ethics stops being abstract and becomes real.

2. The Tribal Brain vs. the Ethical Brain

If your first reaction is, “I can’t imagine letting my five friends die,” congratulations—your tribal brain works. Loyalty, kinship, proximity, and shared history are the oldest moral circuits in the mammalian nervous system.

The problem is simple: tribal morality does not scale.

It is the origin of favoritism, corruption, vigilantism, clan conflict, repression, and atrocity. Every genocide in history begins with a sentence structurally identical to:

“Our people matter more than those people.”

Axio does not fight your loyalty. It fights the idea that your loyalty licenses you to use innocent strangers as fuel for your values.

This is the line most ethical systems blur. Axio draws it in steel.

3. The Axionic Invariant: No Coercive Harm Against Innocents

Axio’s ethical core contains one non‑negotiable rule:

No coercive harm against innocents.

Everything else—values, loyalties, identities, commitments—must be chosen.

Harm, in the Axionic frame, is not about pain. Harm is:

a reduction of another agent’s viable futures caused by your action.

Crucially, this includes probabilistic reductions. If you impose a non‑zero chance of severe injury or death onto an innocent agent, you have already reduced their viable futures—even if the worst case never materializes.

And because any imposed risk deployed to achieve your goals counts as harm, it also counts as coercion:

Coercion is harm used to override another agent’s agency or redirect their trajectory.

This is why the Burning Hospital becomes a perfect crucible. Locking the stranger in the side room is not a neutral “tactical move”; it is the moment where you worsen their risk landscape to advance your ends.

Even if the stranger ultimately survives unharmed, the ethical violation occurred the moment you imposed that additional risk.

Under Axio’s invariant:

Imposed risk is harm.

Harm deployed instrumentally is coercion.

Coercion against innocents is always impermissible.

This shifts the entire analysis: the distinction between “unharmed” and “injured” is morally irrelevant. The moment you worsen an innocent’s survival odds, the line has been crossed.

4. Risk as Harm: Why “Harmless” Locking Is an Illusion

In a disaster environment like a burning hospital, there is no such thing as “harmless confinement.” Smoke, heat, falling debris, and chaotic human behavior make every enclosed space a probabilistic death trap. You cannot guarantee that a locked room will remain safe.

Under Axio’s definition, harm is any reduction in an agent’s viable futures caused by your action. A non‑zero, agent‑imposed increase in the probability of death or injury is harm, regardless of whether the worst case materializes.

This dissolves the notion of “friction”: locking an innocent stranger behind a door in a burning structure always worsens their risk profile relative to where they stand. That alone is coercive harm.

Imposed risk is harm. Harm deployed instrumentally is coercion. Coercion against innocents is impermissible.

Therefore:

There is no version of locking an innocent stranger in a burning building that is ethically permissible under Axio.

The earlier idea of a “harmless constraint” was an artifact of wishful thinking—a way of trying to save the five friends without violating the invariant. Once risk is acknowledged as harm, the exception collapses.

The Burning Hospital must be treated for what it is: a tragedy where the structurally consistent choice does not produce a satisfying outcome, but preserves the one boundary Axio cannot allow you to cross.

5. When Risk Materializes: Injury as Visible Harm

Once we acknowledge that risk itself is harm, actual injury is no longer a threshold event—it is merely the visible manifestation of a violation that already occurred at the moment you imposed the risk.

The stranger’s burns, smoke damage, or lasting trauma do not create the ethical violation; they reveal it. The real harm happened earlier, when you worsened their survival curve to advance your own ends.

It does not matter that:

the harm is small,

the stranger survives,

you love your friends,

you are willing to compensate them,

you accept responsibility.

Those are emotional aftershocks. The structural fact remains:

You used an innocent stranger’s body as an instrument to save others.

Axio forbids this—not because it is sentimental, not because it is moralistic, but because permitting instrumental harm against innocents shatters the invariant required for any non-predatory world.

A society that allows “a little” coercive harm against innocents in emergencies will allow more in worse emergencies, and more still when the powerful label their preferences as emergencies.

This is the hinge that separates Axio from utilitarian arithmetic, from virtue ethical paternalism, and from the tribal instinct to sacrifice outsiders for insiders.

6. Why Compensation Does Not Justify Harm

Axionic Ethics requires compensation when you harm someone. But compensation is a consequence, not a license.

This distinction matters:

Restitution repairs harm.

It does not authorize harm.

You cannot say:

“I’ll hurt you to save my friends, then I’ll pay you later.”

This is the logic of extortion, not ethics.

You may sacrifice yourself for your friends. You may not sacrifice an innocent stranger—even with compensation on the table.

7. When the Stranger Consents

Consent radically changes the topology of the problem. If the stranger freely agrees to be locked in—fully aware of the risk—then the act is no longer coercion.

They have aligned their agency with your goal. This is a valid Axionic move. But note the sharp edge:

Consent must be informed.

Consent must not be extracted by threat.

“Help us or we’ll die” is a description of the world, not coercion.

“Help us or we’ll hurt you” is coercion.

Axio is sensitive to the difference.

8. When the Stranger Blocks You

What if the stranger is not merely present but an obstacle—frozen in panic, flailing in the hallway, or refusing to move in a way that endangers everyone else? This is the last remaining ambiguity, and Axio resolves it using a single structural rule:

You may intervene only if your intervention improves the stranger’s expected survival relative to their current baseline.

This replaces the older language of “minimal, non-harmful force,” which relied on an impossible standard of zero risk. In a fire, zero risk does not exist. What does exist is relative risk:

Pulling someone out of a collapsing corridor and toward a safer exit increases their viable futures. Even if there is a small chance of a twisted ankle, the intervention is net-protective. This is rescue, not coercion.

Shoving someone into a side room that is more exposed to smoke, heat, or structural failure reduces their viable futures. Even if you intend to return for them, the intervention is net-destructive. This is coercive harm.

Forcing an innocent to absorb additional risk so you or your friends can proceed is always forbidden. You may not make their situation worse in order to improve your own.

In short:

Net-improving interventions are permitted. Net-worsening interventions are coercion and forbidden.

This rule removes moral luck, eliminates loopholes, and mirrors the logic of physical rescue: you may only adjust an innocent agent’s position in ways that plausibly leave them better off than they were before you touched them.

Axio does not paralyze you; it forbids using innocents as buffers against tragedy.

9. Why You May Always Harm Yourself but Never an Innocent Stranger

This is the part that feels hardest on the tribal brain and easiest on the rational brain.

Axio draws the boundary cleanly:

You may sacrifice your own agency for your values.

You may not sacrifice someone else’s agency for your values.

That distinction is the entire backbone of Axionic Ethics. It is the firewall between autonomy and atrocity.

If you choose to die with your friends rather than harm the stranger, Axio honors this as tragic but coherent. If you injure the stranger to save your friends, Axio identifies your action as coercive predation.

Nothing about your love for them grants you a license to use an uninvolved agent as a shield.

10. The Structural Explanation for the Hard Bullet

Why is this boundary so absolute?

Because the moment you allow “a little harm” to be imposed on innocents for noble reasons, you have reintroduced the core premise of every coercive moral system:

Need creates claim.

From there, you slide inevitably back into utilitarian arithmetic—the very logic Axio exists to defeat.

Axio refuses the slide.

Axio refuses the arithmetic.

Axio refuses the sacrifice of strangers.

It preserves the invariant even when it hurts. That is what makes it ethics rather than sentiment.

11. The Closing Verdict: The Tragic Invariant

Here is the Axionic answer to the Burning Hospital, stated clearly once we acknowledge that risk is harm and that harm imposed on innocents is always coercive:

Locking the stranger is always impermissible. In a burning structure, confinement always increases their risk profile, and any increase in risk is a reduction of viable futures.

You may only constrain an innocent when the intervention improves their expected survival relative to where they already stand. In a fire, that almost never includes closing a door behind them.

You may sacrifice your own agency, not theirs. Your loyalty does not entitle you to gamble with someone else’s life.

If the stranger consents to absorb risk, the topology changes. If they refuse, your friends may die, and you may die with them, but you do not become a coercer.

If the stranger obstructs, you may intervene only in ways that improve their situation or keep their risk neutral—not worsen it.

The outcome is tragic, not triumphant. Axio does not promise a world where everyone can be saved. It promises a world where no innocent is made into fuel for someone else’s values.

The win state in the Burning Hospital is not saving everyone.

The win state is refusing to become a predator, even when the world burns.

This is the firewall.

This is the structure.

This is the Ethics of Viability.