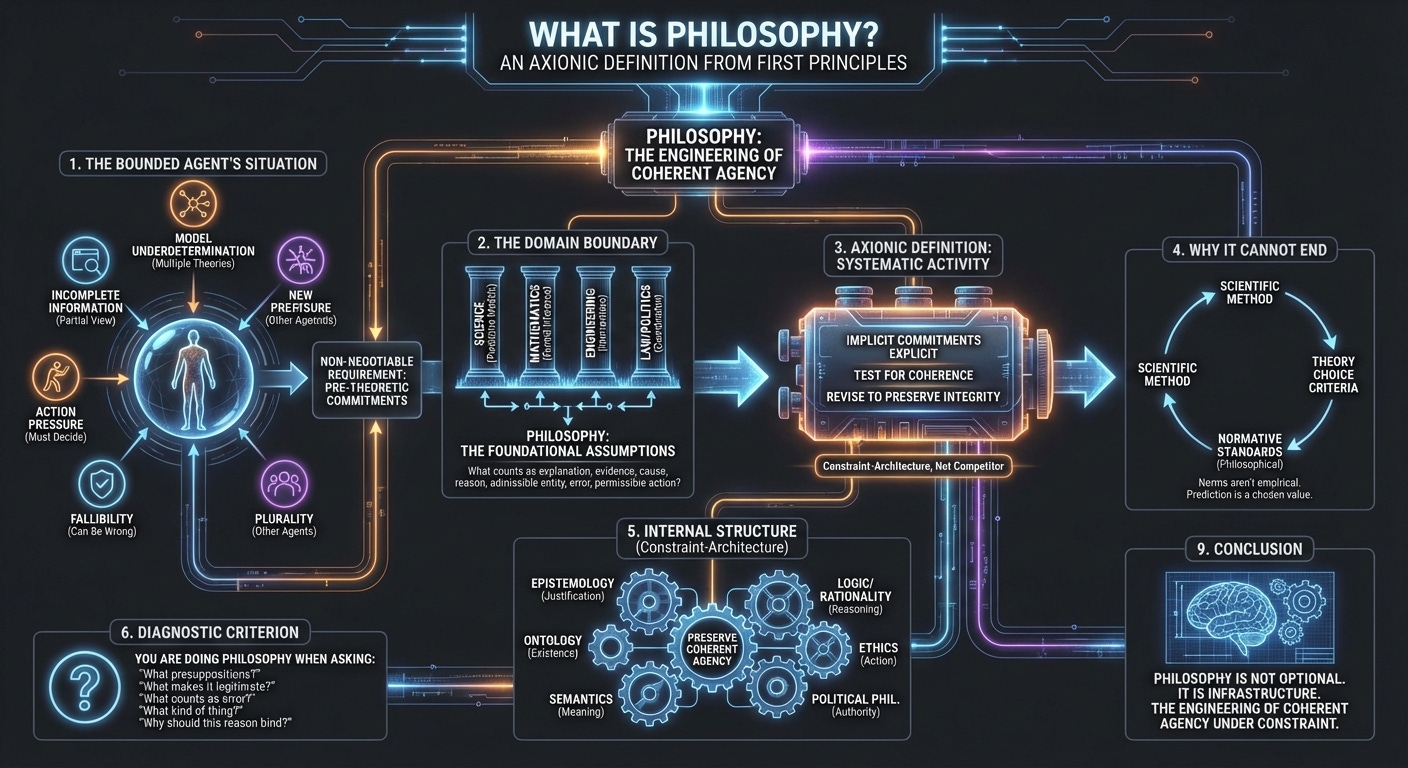

What Is Philosophy?

An Axionic Definition from First Principles

Philosophy is usually introduced historically (“what Plato thought”), stylistically (“armchair reasoning”), or defensively (“questions science cannot yet answer”). All three miss the point.

This essay derives philosophy from first principles. Not as a tradition, temperament, or discourse, but as a structural necessity for any agent capable of reflection and choice.

1. The Agent’s Irreducible Situation

Any bounded agent embedded in reality faces the following facts:

Incomplete information. The world is only partially observable.

Model underdetermination. Multiple explanations fit the same evidence.

Action pressure. Decisions must be made anyway.

Fallibility. The agent can be wrong about both facts and values.

Plurality. Other agents exist, with intersecting incentives and interpretations.

These are not temporary limitations caused by insufficient data, intelligence, or computation. They are structural.

No amount of sensing yields full observability, because relevance itself depends on prior models. No amount of inference eliminates underdetermination, because evidence constrains but does not uniquely select theories. No amount of caution suspends action, because inaction is itself a choice with consequences. No amount of reflection eliminates fallibility, because self-correction presupposes standards that can themselves be mistaken. And no amount of coordination removes plurality, because agents do not share a single vantage or value function.

From these facts follows a non-negotiable requirement:

The agent must adopt rules for believing, reasoning, valuing, and acting before it can do science, engineering, politics, or ethics.

Those rules are not delivered by observation. They are pre-theoretic commitments.

2. The Domain Boundary

Different human enterprises optimize different things:

Science optimizes predictive world-models under shared measurement.

Mathematics optimizes formal inference under axiomatic constraint.

Engineering optimizes interventions under goals and resources.

Law and politics optimize coordination under institutional force.

Each presupposes answers to deeper questions:

What counts as an explanation?

What counts as evidence?

What counts as a cause?

What counts as a reason?

What entities are admissible in a model?

What kinds of error matter?

What actions are permissible?

These questions cannot be answered within the domains that depend on them, because each domain already assumes answers to operate.

Science cannot empirically justify empiricism without circularity; it must already treat observation as epistemically privileged. Engineering cannot derive its goals from technical efficiency alone; efficiency is always relative to a chosen end. Law cannot lawfully justify its own authority; it must presuppose legitimacy to enforce it.

That boundary—the layer of assumptions that make domains possible without being settled by them—is where philosophy begins.

3. Definition

From the above, a precise definition follows.

Philosophy is the systematic activity of making implicit interpretive and normative commitments explicit, testing them for coherence under reflection, and revising them to preserve the integrity of world-modeling and action.

Each term is essential:

Systematic: not intuition trading or rhetoric.

Implicit commitments: the hidden axioms agents already use.

Interpretive and normative: beliefs and reasons for action are inseparable.

Coherence under reflection: the agent must survive self-critique.

Preserve integrity: philosophy is maintenance, not decoration.

Philosophy is not a competitor to science. It is the constraint-architecture that makes science possible.

4. Why Philosophy Cannot End

A persistent error is the claim that philosophy dissolves once science advances far enough.

This fails for a structural reason:

Any scientific method presupposes criteria for theory choice.

Criteria for theory choice are normative.

Norms are not delivered by observation.

Therefore, scientific progress cannot eliminate the need for philosophy.

Even “maximize predictive accuracy” is a normative rule. Prediction does not justify itself; it is chosen because it serves agentic purposes.

As long as agents must decide what to believe and how to act under uncertainty, philosophy remains unavoidable.

5. The Internal Structure of Philosophy

When understood axionically, traditional subfields are not arbitrary divisions but facets of the same job:

Epistemology: prevents belief collapse by constraining justification and error.

Ontology: prevents category confusion by constraining what may exist in a model.

Semantics: prevents interpretive drift by constraining meaning and reference.

Logic and rationality theory: prevents inferential breakdown by constraining reasoning and decision.

Ethics: prevents action incoherence by constraining reasons for action.

Political philosophy: prevents coercive erasure of agency by constraining authority and coordination.

Each answers a different version of the same question:

What must be preserved for agency to remain coherent?

6. A Diagnostic Criterion

You are doing philosophy whenever you ask:

“What are we presupposing here?”

“What makes this explanation legitimate?”

“What counts as an error in this framework?”

“What kind of thing is this, really?”

“Why should this reason bind me?”

Citing data, papers, or authorities does not bypass philosophy. It relies on philosophical commitments about what citations can justify.

7. The Axionic Clarification

The decisive Axionic move is this:

Philosophy is not primarily about discovering new empirical truths. It is about preserving the conditions under which truth-seeking and choice remain meaningful.

This is not a denial of realism or truth. It is a priority claim about function rather than content. Philosophy governs the standards by which truth-claims are intelligible, justified, and action-guiding.

This clarification dissolves several confusions at once:

Why optimization can become anti-rational.

Why coercion undermines legitimacy.

Why error is preferable to stasis.

Why values cannot be universalized without loss of agency.

Philosophy is therefore not speculative excess. It is infrastructure.

8. Axionic Failure Modes

Under an Axionic evaluation—where coherence and agency preservation are the governing constraints—philosophy fails when the following are violated:

Unexamined primitives, which collapse inquiry into dogma.

Authority without delegation, which collapses legitimacy.

Optimization without agency preservation, which yields stasis or tyranny.

Semantics without interpretation, which yields nonsense.

Ethics without consent, which yields coercion.

These are not claims about which doctrines are true, but about which structural patterns preserve or destroy coherent agency under reflection.

What survives these constraints is not opinion. It is structure.

Postscript

Philosophy is not optional. It is what agents are doing whenever they decide what counts, what follows, and what matters.

Axio does not replace philosophy.

It reveals what philosophy always was—once stripped of category errors and rhetorical camouflage:

The engineering of coherent agency under constraint.