When Consensus Entrenches Authority

Proof-of-Stake and the Limits of Capital-Weighted Governance

1. Proof-of-Stake and Proof-of-Work: A Brief Orientation

Before evaluating decentralization, the consensus mechanisms themselves must be defined.

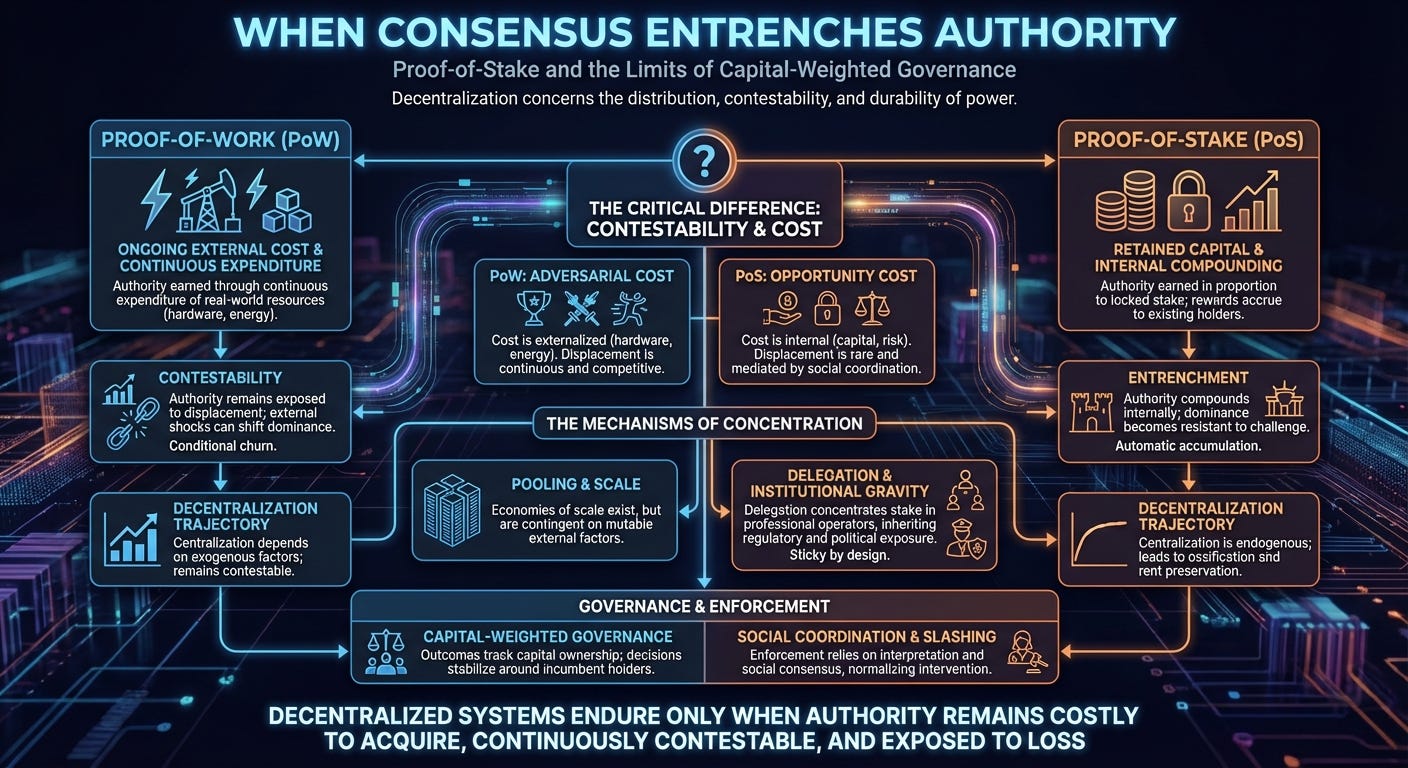

Proof-of-Work (PoW) secures a network by requiring participants to perform ongoing, externally costly computation in order to propose blocks. Authority over state transitions is earned through continuous expenditure of real-world resources. Hardware depreciates, energy is consumed, and advantage must be continually re-earned under changing external conditions.

Proof-of-Stake (PoS) secures a network by granting block proposal and validation authority in proportion to retained capital locked inside the system. Authority is earned by owning stake and maintaining protocol compliance. Rewards accrue to existing stake holders, increasing future authority through internal compounding.

Both mechanisms exhibit centralizing pressures under scale. The distinction lies in how those pressures are mediated and whether control remains contestable over time.

2. Where the Discussion Usually Goes Wrong

Discussions of decentralization often begin with surface metrics: the number of nodes, validators, or clients participating in a network. These metrics are easy to count and easy to advertise. They are also insufficient.

Decentralization is fundamentally about power. It concerns who can determine state transitions, who can block or enforce changes, and whether that authority can be challenged without prior approval. A system in which outcomes are reliably dictated by a small coalition is centralized, even if participation is widespread.

The relevant question is whether authority remains subject to displacement under adversarial conditions.

3. Authority Coupling in Proof-of-Stake

Proof-of-stake systems make a defining architectural choice: authority scales with retained capital.

Validation weight, reward flow, and governance influence all track stake. This coupling is the mechanism that secures the system.

Once authority is bound to capital in this way, accumulation becomes automatic. Participants with larger stakes receive proportionally larger rewards, increasing their future influence and their ability to shape system rules. Power compounds internally rather than being dissipated through competition.

Under these conditions, decentralization becomes transient rather than stable.

4. Contestability, Cost, and Compounding

Decentralized control requires more than cost. It requires adversarial cost—a burden borne by challengers seeking to acquire authority.

In proof-of-work systems, this cost is externalized. Anyone attempting to seize control must incur real-world expenditure under prevailing market conditions. Economies of scale exist, and large miners often secure advantages in hardware procurement and energy pricing. These advantages matter, yet they remain contingent on mutable external factors such as regulation, geography, supply chains, and energy markets.

In proof-of-stake systems, the primary cost is opportunity cost borne by incumbents. Capital is locked and exposed to market risk, yet acquiring that capital does not require the continuous, competitive burn of resources that characterizes mining. Authority compounds internally, and relative control increases through protocol rewards rather than displacement.

The result is entrenchment rather than churn.

5. Delegation and Institutional Gravity

Although proof-of-stake is often described as broadly empowering, most participants do not run validators themselves. Operational complexity, uptime requirements, and risk management encourage delegation.

Delegation concentrates stake in a small number of professional operators. When those operators are exchanges or regulated service providers, the network inherits their legal and political exposure. Regulatory obligations, jurisdictional constraints, and compliance incentives propagate upward into protocol governance.

Mining pools in proof-of-work systems also concentrate coordination, yet their authority remains weakly bound. Hashpower can be redirected rapidly, and pool exit carries minimal delay. In proof-of-stake systems, delegation is sticky by design. Bonding periods, slashing exposure, and protocol-level delays convert coordination into durable control.

Authority therefore becomes mediated through institutions whose incentives are external to the network’s original neutrality claims.

6. Capital-Weighted Governance Dynamics

Proof-of-stake networks frequently adopt stake-weighted governance mechanisms. Participation rates tend to be low, while large stakeholders remain consistently engaged.

Governance outcomes therefore track capital ownership closely. Protocol changes are negotiated among dominant holders, upgrades follow elite consensus, and dissent is resolved through economic pressure or coordination barriers.

Decision-making authority stabilizes around incumbent capital.

7. Enforcement, Slashing, and the Social Layer

To maintain security, proof-of-stake systems rely on slashing. Slashing requires definitions of misbehavior and coordinated enforcement.

These processes depend on interpretation. Timing, context, and intent matter. Enforcement decisions are shaped by social consensus among validators and developers.

All consensus systems ultimately depend on social coordination. The difference lies in how often and where it is invoked. In proof-of-work systems, social intervention functions as a rare override aimed at constraining hostile economic actors. In proof-of-stake systems, social coordination is embedded into routine enforcement and governance.

Authority enforcement becomes normalized rather than exceptional.

8. Incentives and Long-Term Trajectories

Large stakeholders optimize for stability and return. This includes preserving revenue streams, minimizing disruption, aligning with regulators, and discouraging changes that threaten established positions.

These incentives favor ossification and rent preservation. The divergence between incumbent incentives and open contestability emerges gradually and compounds over time.

9. Churn, Stability, and Decentralization

Decentralization does not require constant turnover. It requires credible contestability.

Proof-of-work systems enforce conditional churn by tying authority to ongoing external expenditure. Dominance often appears stable in practice, yet it persists only while external conditions remain favorable. Authority remains continuously exposed to displacement even when turnover does not occur.

Proof-of-stake systems minimize churn under normal operation and externalize resolution to social coordination during crises. Authority remains stable until disrupted from outside the protocol.

10. The Axio Assessment

Both proof-of-work and proof-of-stake systems centralize under scale. The distinction lies in the mechanisms governing that centralization.

Proof-of-work centralization depends on exogenous factors and remains contestable through external shocks. Proof-of-stake centralization is endogenous. Authority compounds internally through protocol rewards, making dominance increasingly resistant to challenge.

Proof-of-stake reshapes decentralization into a property of appearance rather than constraint.

Decentralized systems endure only when authority remains costly to acquire, continuously contestable, and exposed to loss.