Why There Is Something Rather than Nothing

A Modal Resolution

Abstract

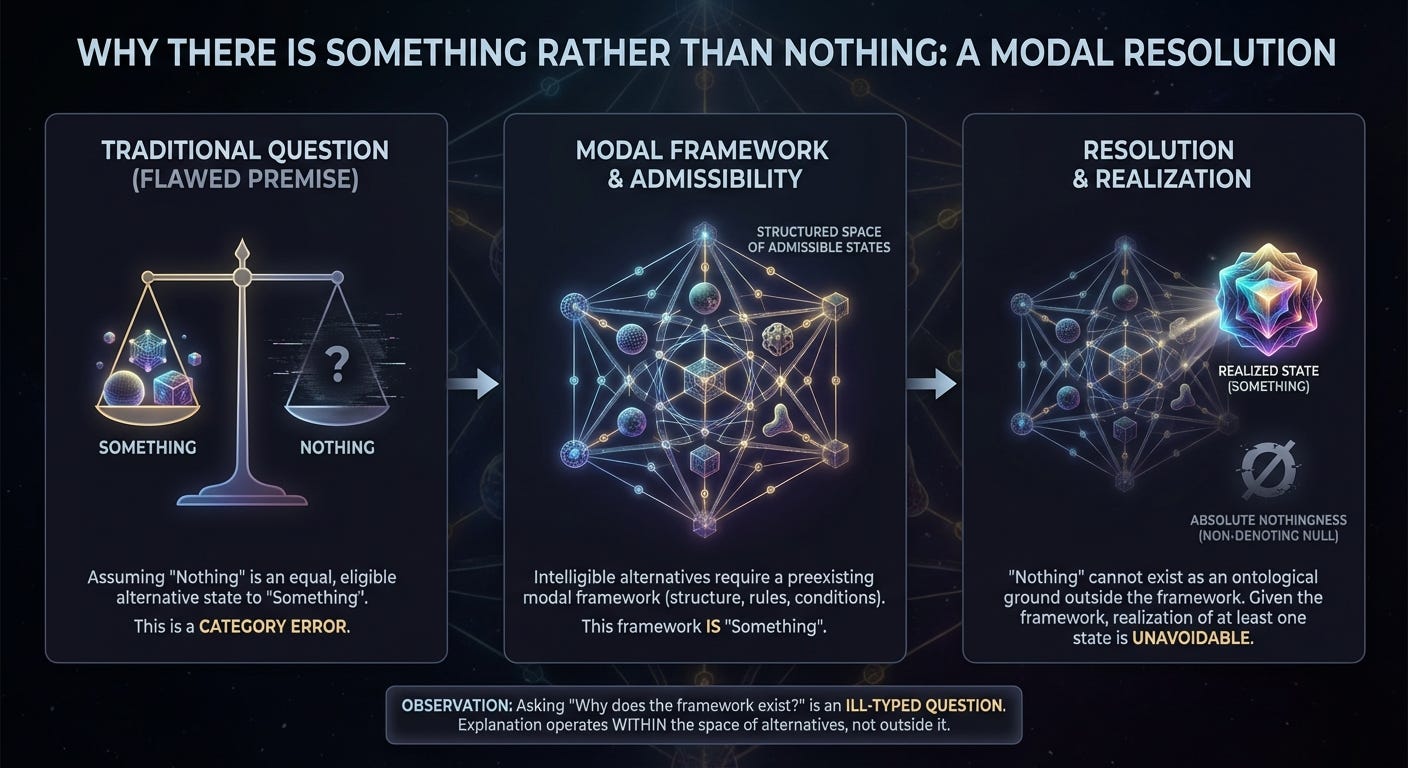

The question “Why is there something rather than nothing?” has long been treated as a fundamental metaphysical riddle, resistant to analysis and often invoked as the terminus of explanation. This paper argues that the appearance of depth is illusory. Once a structured space of admissible states is acknowledged—once there exist intelligible alternatives at all—the realization of at least one state is unavoidable. Absolute nothingness cannot serve as an ontological ground; it can arise only as a counterfactual contrast defined relative to an already-existing modal framework. The persistence of the question reflects a category error: the treatment of “nothing” as a candidate state of reality rather than as a non-denoting null whose apparent intelligibility depends entirely on the structure it purports to negate.

1. The Question and Its Presuppositions

The traditional formulation of the question presupposes more than it reveals. To ask why there is something rather than nothing is to assume, first, that “nothing” constitutes a coherent alternative to “something,” and second, that both terms are eligible for comparison within a single explanatory space. These assumptions are rarely articulated, let alone defended. They are inherited from a pre-modal metaphysical picture in which absence is treated as symmetrical with presence and possibility as secondary to being.

That symmetry does not survive scrutiny. Once the conditions under which alternatives can be meaningfully contrasted are made explicit, the question begins to dissolve.

2. Modal Realization as a Point of Departure

Consider the following principle:

Modal Realization Principle

All physically admissible states are realized on some timeline.

The principle is intentionally spare. It does not invoke necessity, purpose, or design. It asserts only ontological completeness: admissibility is not merely conceptual but corresponds to instantiation within a structured space of alternatives.

On this view, reality is not exhausted by a single history but consists in a space of realized possibilities. Within such a framework, the traditional question becomes precise: does “nothing” belong to the space of admissible states?

3. Admissibility and the Status of Nothing

If “nothing” is not admissible—if it does not qualify as a state within the space of alternatives—then the question collapses immediately. There was never a genuine contrast to explain. One does not ask why reality fails to instantiate incoherence or contradiction, any more than one asks why triangles have three sides. The purported alternative was never in the comparison class.

Suppose, instead, that “nothing” is admitted as admissible. This concession does not restore the mystery; it merely relocates it. Admissibility itself presupposes a modal framework: a structured space in which states can be distinguished, evaluated, and said to obtain or fail to obtain. That framework is not nothing. It is structure.

Accordingly, even if “nothing” is admitted, it cannot be ontologically fundamental. It exists, at most, as a contrast internal to a prior space of admissible states. It does not precede that space; it depends upon it.

4. Eligible Alternatives and Non-Denoting Nulls

At this juncture a crucial distinction must be drawn. Contrastive explanations—explanations of the form “Why A rather than B?”—require that both A and B be eligible alternatives, capable of standing within a shared explanatory space.

Absolute nothingness, when defined as the absence of all structure, coherence, modality, and evaluability, fails this requirement. It is not an excluded possibility but a non-denoting null. Such nulls are not suppressed by reality; they are not unrealized options awaiting explanation. They are simply not members of the space of alternatives. No explanatory debt is incurred by their absence.

An appeal to “global nothingness”—the absence of the modal framework itself—does not strengthen the contrast. It abolishes the contrastive frame altogether, at which point the question “why rather than” no longer applies.

5. Statehood, Not Semantics

It may be objected that this argument merely demonstrates the limits of language or conceptualization rather than the limits of reality itself. This diagnosis is mistaken. The constraint at issue is not linguistic expressibility but ontological eligibility: what counts as a state capable of standing in a contrastive relation at all.

The claim is not that reality conforms to our language, but that contrastive explanation presupposes states with determinate identity conditions. Where such conditions are absent, exclusion is not explanatory—it is categorical. Absolute nothingness is not ruled out by description; it fails to qualify as a state in the first place.

This is no more a semantic maneuver than the exclusion of square circles from geometry. The limitation is constitutive, not verbal.

6. The Derivative Status of Counterfactual Nothingness

One might attempt to salvage “nothing” by relegating it to the counterfactual domain. Yet counterfactuals are inherently dependent entities. They presuppose a factual base, a notion of divergence, and a modal framework within which alternatives are assessed. A counterfactual without such anchoring conditions is undefined.

Consequently, even if “nothing” is admitted counterfactually, it cannot be ontologically prior to the structure that renders counterfactual discourse meaningful. Counterfactual existence is not a weakened form of fundamentality; it is derivative through and through.

7. Vantage and Constitutive Constraints

Any attempt to pose the original question already presupposes a vantage: a standpoint from which alternatives are compared and contrasted. Once such a vantage exists, existence is already instantiated. The question therefore presupposes precisely what it purports to explain.

This is not an epistemic or anthropic observation. It does not claim that the world exists because observers exist. Rather, it identifies a constitutive constraint on contrastive explanation: to meaningfully ask why A rather than B, one must already occupy a framework in which A and B can obtain or fail to obtain. That framework is not inferred from observation; it is presupposed by intelligibility itself.

8. Objections Considered Briefly

It may be objected that nothingness “does not care” whether it denotes or coheres. Yet indifference is not a property of non-denotation. If nothingness fails to denote, it cannot function as an alternative, and the contrastive question loses its footing.

Others may insist that if nothing obtains, all constraints vanish. But the conditional formulation—“if nothing obtains”—already presupposes modality and structure. To employ structure in order to deny structure is not profundity but inconsistency.

A final objection holds that this argument proves too much, likening it to the claim that intelligence is necessary simply because inquiry presupposes intelligence. The analogy fails. Intelligence is an epistemic enablement; a world without intelligence is coherent. Modal structure, by contrast, is an ontological precondition for the intelligibility of alternatives. Remove intelligence and the world remains; remove modality and “nothing” ceases to denote.

9. Resolution

There is something rather than nothing because the existence of intelligible alternatives already requires a structured space of admissible states, and within such a space the realization of at least one state is unavoidable. Absolute nothingness cannot function as an ontological ground. It can appear only as a relational absence within a framework whose existence it presupposes.

The deepest fact, therefore, is not that something exists, but that intelligible alternatives require a structured space of admissible states. Given such a space, realization is not optional but inevitable.

9.1 Explanation, Bedrock, and Ill-Typed Questions

At this point a familiar meta-question arises: why does the modal framework itself exist rather than not exist? This question is not deeper than the original; it is ill-typed. Explanation operates within a space of admissible alternatives. Asking why that space exists attempts to step outside the conditions under which explanation is possible at all.

The modal framework is not posited as a cause, an entity, or a necessary being. It is identified as the minimal structure required for the intelligibility of alternatives. Where intelligibility ends, explanation does not fail—it ceases to apply.

10. Compressed Formulation

There is something rather than nothing because even the possibility of nothing presupposes a structured space of admissible states, and once such a space is given, realization of at least one state cannot fail to occur.

Addendum: Philosophical Positioning

This essay should be read neither as a causal explanation of existence nor as a semantic analysis of the word “nothing,” but as a constitutive examination of what can count as a state of affairs in contrastive explanation. Its method is transcendental rather than theological: it does not seek a sufficient reason for existence, but identifies the conditions under which the question of existence is intelligible at all. In this respect, the argument is continuous with Kantian and Wittgensteinian traditions that diagnose certain metaphysical questions as ill-typed, while drawing on contemporary analytic metaphysics to articulate those typing constraints in terms of statehood, identity conditions, and modal admissibility. The appeal to a Modal Realization Principle reflects a substantive metaphysical commitment, acknowledged rather than defended here; the essay’s core claim is conditional: given a structured space of admissible states, the contrast “something rather than nothing” cannot be sustained. Readers seeking a causal origin story, a theological grounding, or a purely linguistic therapy will therefore find that the argument neither competes with nor accommodates those projects, but reframes the problem they presuppose.