Against Moral Extortion

What Singer’s Shallow Pond Gets Wrong

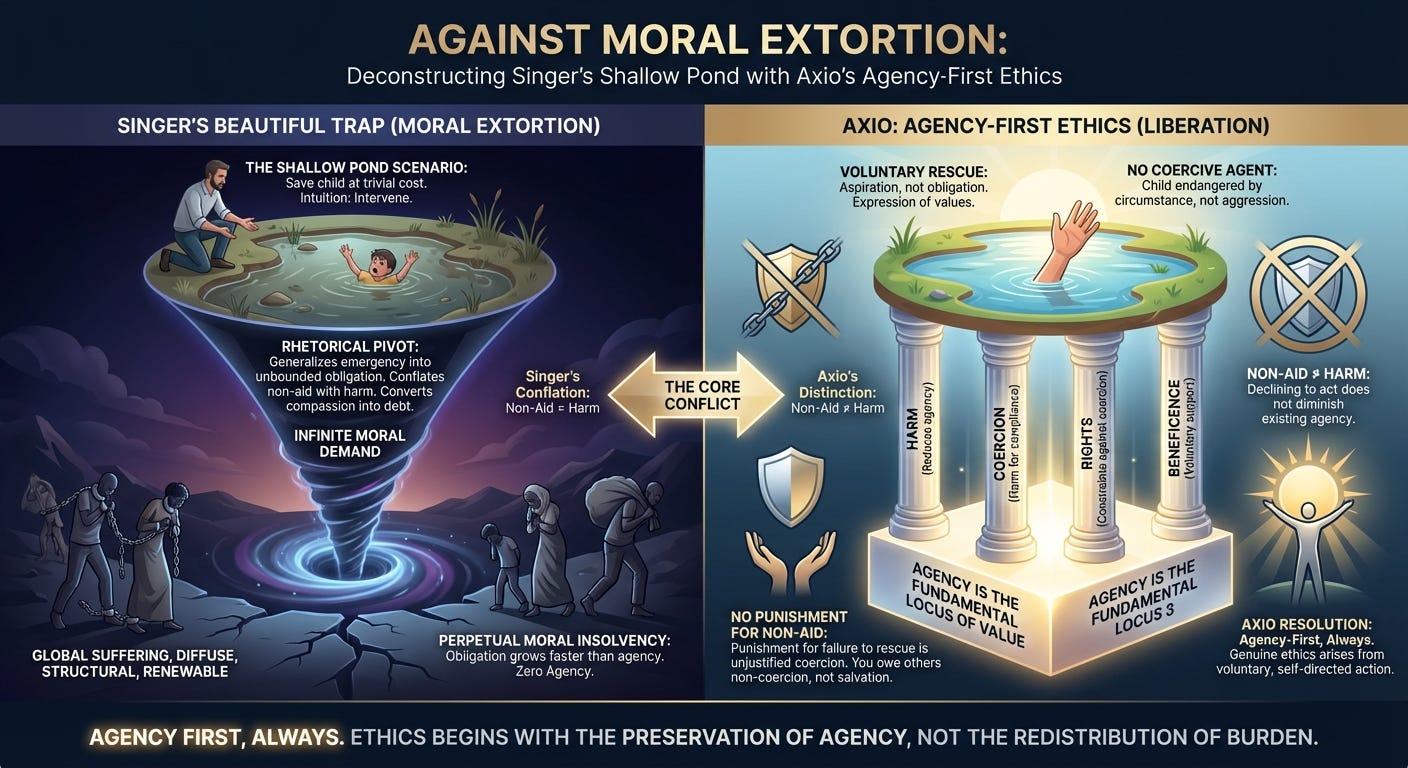

1. The Setup: Singer’s Beautiful Trap

Singer’s Shallow Pond begins with a simple scenario: you are walking past a shallow pond and see a child drowning. You can save the child at trivial cost—muddy clothes, a few lost minutes—and nearly everyone judges intervention to be the obvious choice. Singer then performs a deliberate pivot: he treats this acute emergency as the archetype of moral obligation itself. If you would save the nearby child, he argues, you must also save distant strangers whom you can help at low cost.

This is the rhetorical hinge on which his entire argument swings. The thought experiment trades on your immediate, emotionally salient intuition and generalizes it into an unbounded, enforceable demand.

Axio rejects this move outright. The equivalence between emergency beneficence and standing obligation is a category mistake.

Singer’s parable succeeds rhetorically because it quietly conflates non-aid with harm, converting compassion into debt. Under Axio’s agency-first ethics, that conflation is invalid.

2. Agency as the Ethical Primitive

Axio begins from a single, structural axiom: agency is the fundamental locus of value. Ethical reasoning governs the preservation, coordination, and extension of agency—not the maximization of welfare or the enforcement of altruism.

From this perspective:

Harm is an act that reduces another agent’s agency.

Coercion is harm deployed to gain compliance.

Rights are constraints justified only to prevent coercion.

Beneficence is voluntary agency support; it cannot be mandated.

This framework is coherent without external moral authorities. It avoids the utilitarian error of treating persons as interchangeable welfare vessels and the deontological error of positing unconditional obligations. Agency—not need, not suffering—is the conserved quantity.

With this structure in place, the weakness in Singer’s inference becomes unmistakable.

2.1 The Conditionalist Diagnosis

Singer’s argument appears forceful only because it smuggles in a hidden interpretive condition: that agents possess a default obligation to maximize the welfare of strangers. Conditionalism exposes the flaw. All moral claims presuppose background conditions. Singer treats his preferred condition as universal when it is merely optional.

Once surfaced, the argument disintegrates. His conclusion expresses one moral worldview, not a logical necessity.

3. Emergency Rescue Is Not a Moral Debt

In the shallow pond, no coercive agent is present. The child is endangered by circumstance, not aggression. The water and the child’s inability to stay afloat constitute the danger; no one is morally culpable.

Intervening is therefore a voluntary act of agency-preservation, not the repayment of a debt. You are preventing a loss that no agent caused, not correcting a wrong.

Under Axio, only coercive harm generates enforceable claims. Need does not generate claim.

A claim, formally, is a warranted demand for coercive enforcement—a justification for limiting another’s agency to restore or protect one’s own. Only coercive harm generates such warrants. Natural misfortune does not.

The boundary is clean: when you cause the danger—through negligence, recklessness, or coercive action—you create a claim. Pushing someone into water, disabling a flotation device, or otherwise initiating the loss of agency grounds an obligation to rescue.

The original pond scenario contains no such claim. Even if you possess the only life preserver, withholding it remains non-aid, not coercive harm; nature endangers the drowning agent, not you. The decision to act expresses your values, not a universal duty.

4. The Distinction Singer Erases

Singer’s extension from the shallow pond to global charity depends on collapsing two situations that share emotional texture but not moral structure. The intuitive force of the pond rescue comes from its simplicity: the threat is local, visible, agent-neutral, and removable through a single, low‑cost act. Nothing competes with your ability to restore the child’s agency.

Global suffering has none of these features. It is diffuse, structurally embedded, coordination‑heavy, and indefinitely renewable. Any intervention you make interacts with complex systems; second‑order effects proliferate; costs and trade‑offs compound. There is no natural endpoint at which one can say, “The obligation is complete.”

Conflating these categories commits what Axio calls the non‑aid–harm fallacy: treating the absence of voluntary beneficence as equivalent to coercive harm. Once this boundary is erased, moral demand becomes unbounded by design. The immediacy of the emergency is repurposed to justify obligations that apply everywhere, always, and to everyone.

This is not ethical reasoning; it is rhetorical maneuvering.

5. Why Failure to Rescue Is Not Punishable

Here is the Axio position with maximal clarity:

Failure to rescue in an uncoerced emergency is ethically disappointing but never a rights-violation. Punishment would be an act of unjustified coercion.

Non-aid is not harm. Declining to increase another’s agency does not diminish the agency they already possess. Under Axio, coercion is justified only to counter coercion—never to enforce ideals of beneficence.

Singer’s logic requires treating non-aid as morally indistinguishable from killing. That move licenses a punitive morality in which individuals can be coerced for failing to volunteer their agency. The persuasion comes from turning compassion into obligation, and obligation into moral leverage.

Axio rejects this chain at every step. You owe others non-coercion, not salvation.

Critics will insist on a middle ground—a space for “moral obligation” that is not legal but still claims binding force through guilt or social pressure. Axio rejects this imagined category outright. Moral pressure is coercion translated into emotional currency: an attempt to extract unchosen labor without admitting the use of force. If a duty cannot be justified by a genuine rights-violation, it is not a duty; it is a request to your values, and you are free to accept or decline.

Axio is not a zero-duty ethic; it is a zero-unchosen-duty ethic. Duties arise from promises, contracts, and harms you cause—not from the mere existence of need.

6. The Burnout Zone of Infinite Moral Demand

If Singer’s reasoning held, moral obligation would scale with global suffering. Every non-essential purchase becomes a moral crime. Every retained resource becomes evidence of negligence. The logical endpoint is perpetual moral insolvency.

An ethical system that consumes the agent’s own agency to satisfy unbounded demands is self-negating. It cannot sustain the very agents it expects to act.

Singer’s framework belongs to a broader class of infinite-demand systems: Pascalian mugging, totalizing utilitarianism, cosmopolitan duty traps. All share the same pathology: obligation grows faster than agency.

Any ethic that terminates in infinite obligation terminates in zero agency.

7. The Axio Resolution

Singer is correct that voluntary rescue can be beautiful. Choosing to preserve life at trivial cost reveals the aspirational dimension of agency.

But aspiration is not obligation. And it is never enforceable.

Axio preserves the beauty of voluntary rescue without collapsing into coercive maximalism.

You may judge the non-rescuer harshly if your values demand it; such condemnation is an expression of your agency, not a binding claim on theirs.

The Axio stance

Save the child if it aligns with your values. Refusing rescue violates no rights. Punishing non-aid is coercion. Need never generates claim; only coercive harm does.

Postscript

The Shallow Pond is a mirror. Singer wants the reflection to show guilt, obligation, and debt. Axio reframes the moment: what you see is your own agency in action.

Nature makes no demands. Only agents can. Ethics begins with the preservation of agency, not the redistribution of burden.

Singer’s project is to conscript. Axio’s project is to liberate.

In a world shaped by accidents and fragility, genuine ethics arises from voluntary, self-directed action—not from universalized compulsion.

Agency first, always.