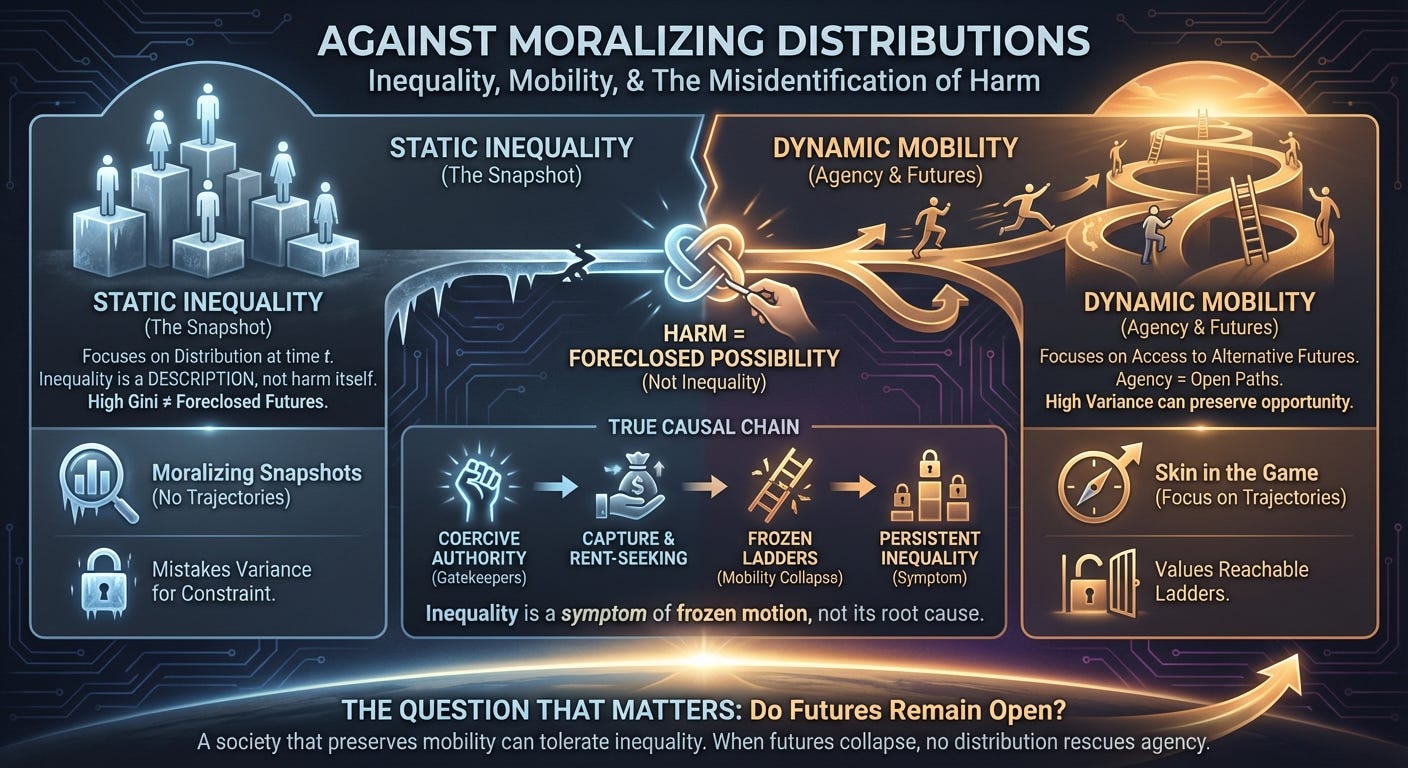

Against Moralizing Distributions

Inequality, mobility, and the misidentification of harm

A recurring confusion in political and moral discourse is the treatment of inequality as if it were itself a form of harm. It isn’t. Inequality is a distributional description. Harm is a structural constraint. Conflating the two replaces causal analysis with moralized snapshots.

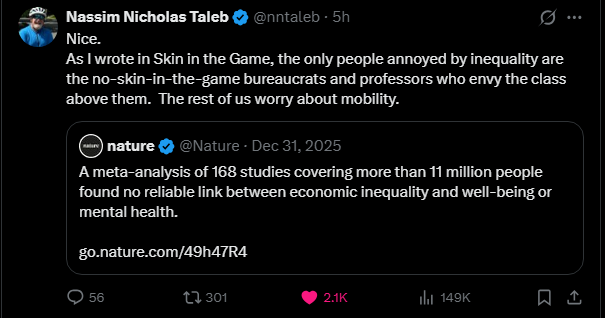

This confusion resurfaced recently when a widely circulated meta-analysis reported no reliable link between economic inequality and well-being or mental health. In response, Nassim Nicholas Taleb summarized the situation bluntly: people who complain about inequality are typically those without skin in the game; people actually living in the world worry about mobility.

That remark points to a distinction most social science quietly erases.

Inequality is static. Agency is dynamic.

Inequality describes how resources are distributed at a moment in time. It says nothing about how positions change, how trajectories unfold, or how futures branch. Two societies with identical income distributions can feel radically different to inhabit depending on whether movement is possible.

From an Axio perspective, this distinction is decisive. What matters for human flourishing is not where one sits on a ladder at time t, but whether future ladders remain reachable. Agency consists in access to alternative futures. When that access collapses, harm occurs.

A society with high variance and open paths preserves agency. A society with frozen positions destroys it. Treating those cases as morally equivalent because they share a Gini coefficient is a category error.

Why inequality rarely maps cleanly to well-being

The meta-analysis circulated by Nature surprised many readers only because it challenged an assumption they never examined. The relationship between inequality and well-being is highly conditional, institution-dependent, and unstable across contexts.

Humans adapt well to relative rank differences. We evolved in hierarchical environments. What we do not adapt to is foreclosed possibility.

Psychological distress correlates strongly with loss of control, lack of optionality, and predictable stagnation. Those are features of immobility, not inequality. A person who expects improvement can tolerate disparity. A person trapped in place cannot tolerate even modest gaps.

This explains why redistribution schemes that cosmetically flatten outcomes while leaving barriers intact often fail to improve lived experience. They optimize a surface metric while quietly shrinking the set of futures a person can realistically pursue.

Mobility does not collapse because of inequality

At this point a common objection appears: extreme inequality, it is said, reduces mobility by enabling regulatory capture, rent-seeking, or entrenchment.

This reverses the causal order.

Inequality does not freeze ladders. Coercive institutions freeze ladders. Only where authority exists to grant exclusive privileges, enforce barriers, or restrict entry can resources—whether money, status, or connections—be converted into constraints on others’ futures.

The correct dependency chain is:

Coercive authority → capture becomes possible → mobility collapses → persistent inequality emerges.

Inequality is therefore a symptom of frozen motion, not its root cause. Without coercive gatekeeping, wealth cannot enforce stasis. It dissipates, competes, or is overtaken.

When inequality correlates with immobility, the mediator is always institutional constraint. Treating inequality itself as the driver misidentifies the failure mode and invites solutions that leave the true bottleneck untouched.

Competition is not coercion

A common confusion is to treat competitive disadvantage as coercion. Axio draws a sharp distinction.

Competition selects among paths. Coercion removes them.

A firm that outcompetes rivals does not block entry. A platform with network effects does not forbid exit. Even predatory behavior fails without mechanisms that enforce exclusion across time—mechanisms that depend on barriers to re-entry, blocked recombination, or enforced immobility.

Axio treats difficulty, risk, and low probability as compatible with agency. Only enforced impossibility constitutes harm. Low odds are not closed doors. Difficulty is not constraint.

Skin in the game as an epistemic filter

Taleb’s invocation of skin in the game is not an insult. It is a diagnostic. Exposure to downside risk forces attention onto trajectories rather than snapshots. If your choices affect your survival, you care about path dependence, variance, and exits. If they do not, you are free to moralize static outcomes.

This is why inequality discourse is dominated by classes whose positions are relatively insulated. Their lived problem is positional comparison without volatility. They mistake that condition for universal moral insight.

People operating under real risk conditions rarely ask whether outcomes are equal. They ask whether movement remains possible. They ask whether today’s loss can be tomorrow’s gain. They ask whether the game is still playable.

The agency lens

Axio treats harm as reduction in agency: a contraction of reachable futures relative to an agent’s vantage. Under that definition, inequality has no independent moral status. It matters only insofar as it reflects or contributes to blocked transitions—and when it does, the causal mechanism is always constraint, not variance.

This framing dissolves several persistent confusions. It explains why inequality can rise without social decay, why equalization can coincide with despair, and why mental health tracks perceived mobility far more reliably than income dispersion.

The question that matters

The moral question is not whether outcomes look fair in a snapshot. It is whether futures remain open.

A society that preserves mobility can tolerate inequality. A society that suppresses mobility cannot tolerate even perfect equality.

When futures collapse, no distribution rescues agency.

Ask less about who has what. Ask whether the game still admits motion.