Constraint, Formalism, and Empiricism

Why Math and Science Are Not Philosophy

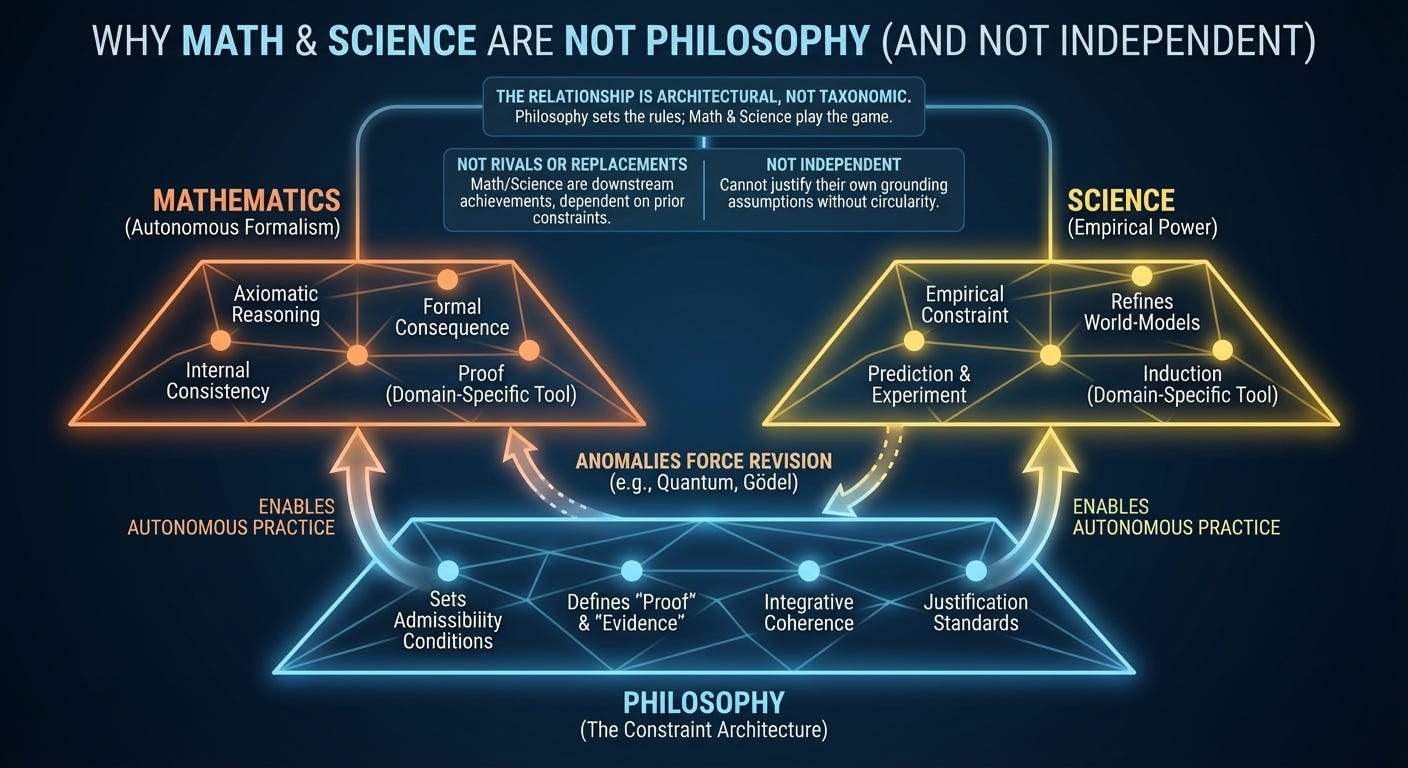

A persistent confusion shadows modern intellectual life. It appears in two opposite claims, both spoken with confidence and both mistaken.

One says that philosophy is obsolete—that science and mathematics have finally replaced it. The other says that mathematics and science are merely branches of philosophy, latecomers that grew out of earlier speculation. These claims disagree, but they share a deeper error. Both mistake historical lineage for structural role.

The relationship between philosophy, mathematics, and science is not a matter of ancestry or rivalry. It is a matter of precondition and consequence.

The Category Error

Philosophy is often treated as one discipline among others, a sibling to mathematics or science with a different style and subject matter. That framing already misfires. A discipline is defined by internal standards of success. It has methods for resolving disputes, criteria for correctness, and procedures for progress. Mathematics has proof. Science has experiment and prediction.

Philosophy has none of these domain-specific tools—by design. Its standard is not empirical verification or formal proof, but integrative coherence under reflection.

Philosophy does not tell you which theorem is correct or which experiment succeeded. It asks what counts as a theorem, why proof binds belief, what counts as evidence, and why prediction should matter at all. These questions cannot be answered within mathematics or science, because those domains already rely on answers to operate.

This immediately disqualifies philosophy from being a sibling discipline. But it also disqualifies mathematics and science from being independent.

The relationship is architectural, not taxonomic.

Constraint, Formalism, and Empiricism

Philosophy operates at the level of constraint. It fixes the background conditions under which inquiry is intelligible: what counts as explanation, justification, error, and success. Once those constraints are in place, mathematics and science become possible as autonomous practices.

Mathematics explores formal consequence under stipulated axioms. Science refines shared world-models under empirical constraint. Engineering applies those models to intervention. Each activity is internally disciplined and methodologically rigorous, but none can justify the framework that makes it possible.

That framework is inherited, not derived.

This does not make philosophy static or authoritarian. When empirical inquiry encounters persistent anomalies—such as quantum nonlocality, relativistic spacetime, or evolutionary explanations of cognition—it does not bypass philosophy. It forces a revision of the admissibility conditions themselves. Philosophy sets the rules, but the game can expose cracks in the rules that require patching.

The dependence is asymmetric, but not inert.

Mathematics: Autonomous, Not Self-Grounding

Once axioms and inference rules are fixed, mathematics is ruthlessly internal. Proof does not care who you are or what you believe. No philosophical argument can overturn a valid derivation, and no metaphysical debate is required to settle a theorem.

In that sense, mathematics is fully autonomous.

But that autonomy rests on assumptions mathematics itself cannot defend. Mathematics cannot explain why axiomatic reasoning is legitimate in the first place, why consistency matters, why some formal systems are fertile and others barren, or why formal truth should constrain belief about the world. It cannot explain why mathematics applies to physical reality at all.

These are not mathematical questions. They are questions about the meaning and role of mathematics—questions mathematics must presuppose but cannot answer.

This is not a sociological limitation. It is a structural one. Gödel showed that sufficiently expressive formal systems cannot establish their own consistency from within. Mathematics is powerful precisely because it inherits constraints it does not generate.

Science: Empirical Power Without Epistemic Closure

Science is the most successful method humans have ever developed for modeling the world. Prediction, replication, and error correction give it unmatched practical authority. Within its domain, science does not need philosophical supervision.

But science also rests on commitments it cannot empirically establish. Observation is treated as epistemically privileged. Induction is assumed to be legitimate. Simpler explanations are preferred. Predictive success is treated as meaningful. Models are assumed to refer to a mind-independent reality. Truth is taken to be preferable to mere instrumental success.

None of these commitments are discovered by experiment. They are not falsified or confirmed by data. They are the background rules that make data intelligible in the first place.

A scientific attempt to justify empiricism empirically would already be assuming what it tries to prove. Science works because these commitments are inherited silently, not because they are self-grounding.

Why “Sub-Discipline” Fails

Calling mathematics or science a sub-discipline of philosophy misunderstands what philosophy does. Philosophy does not evaluate proofs, run experiments, or adjudicate empirical disputes. It does not supply domain-internal methods.

What philosophy supplies are admissibility conditions: what kinds of reasoning count, what kinds of entities may be posited, what kinds of justification are acceptable. A parent discipline governs outcomes. Philosophy governs the conditions under which outcomes make sense at all.

That is why philosophy cannot settle questions inside mathematics or science—and why mathematics and science cannot eliminate philosophy.

Why “Independence” Fails

The opposite error—treating mathematics and science as independent of philosophy—is more damaging. It produces scientism, naïve formalism, and silent norm smuggling.

The illusion of independence persists only as long as no one asks why a method should be trusted. The moment you appeal to success, usefulness, prediction, elegance, or simplicity, you have already stepped outside the domain and into philosophy. Independence collapses the moment justification is demanded.

What looks like independence is actually successful constraint inheritance. The background rules are doing their job so well that they disappear from view.

The Axionic Clarification

Under an Axionic evaluation, the relationship is precise and non-mystical.

Philosophy provides the constraint architecture required for coherent agency. Mathematics and science are tools that become possible once those constraints are fixed. Philosophy determines what counts as explanation, justification, error, and legitimacy. Mathematics and science then operate freely within that space.

This is why philosophy feels invisible when things are going well—and unavoidable when they are not.

A Single Test

There is a simple diagnostic that dissolves the confusion.

Can this domain justify its own standards of success without circularity?

Mathematics cannot. Science cannot. Engineering cannot. Law cannot.

Only philosophy even attempts the task. That does not make philosophy superior. It makes it prior.

Postscript

Mathematics and science are not philosophy. They are not rivals to it, and they are not replacements for it. They are downstream achievements—fragile, powerful, and dependent.

Philosophy is what keeps those achievements intelligible, legitimate, and worth doing.

Or, compressed axionically:

Philosophy sets the rules of admissibility.

Mathematics and science play the game.

When the rules are coherent, the game flourishes.

When they are not, no amount of data or computation can save it.