Regret Is Not a Policy Metric

Why Legalization Is Judged Against an Impossible Standard

The Regulatory Counterfactual Fallacy

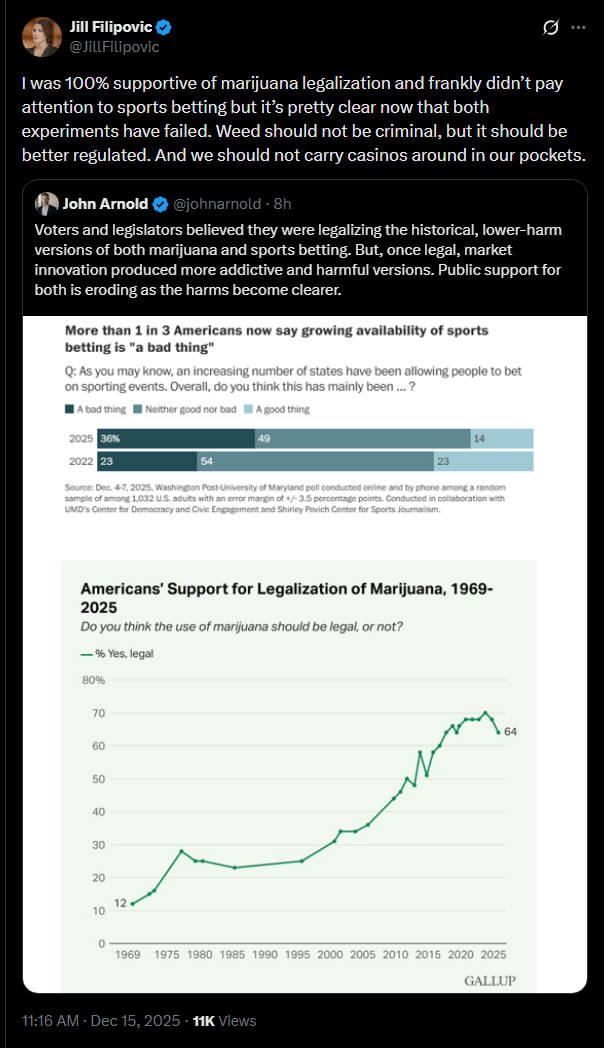

Recent claims that marijuana legalization and sports betting have “failed” rely on a shared conceptual error: they compare real outcomes against an imaginary counterfactual in which adults are granted freedom only on the condition that they continue to behave moderately, discreetly, and in ways that do not disturb elite sensibilities.

This counterfactual is never defended. It is simply assumed. The assumption is that legalization was supposed to preserve historical, low‑intensity forms of vice, while removing only the criminal penalties. When reality diverges from this hope, the divergence is labeled “failure.”

That framing is incoherent. Legalization is not a promise about outcomes; it is a change in constraints. Removing legal barriers does not freeze culture, technology, or incentives in place. It allows preference, innovation, and competition to operate openly.

Calling this outcome a failure is equivalent to calling evolution a failure for producing predators. The complaint is not that the process malfunctioned, but that it revealed truths its proponents found uncomfortable.

Preference Revelation Is Not Policy Failure

Markets do not invent demand; they reveal it under conditions of reduced friction.

High‑THC cannabis did not arise because legalization corrupted users. It arose because a substantial subset of users already preferred stronger effects, and because producers in competitive markets naturally optimize along dimensions consumers reward. This is not a pathology of legalization; it is a basic property of economic systems.

Expecting markets to converge on moderation without explicit constraints is equivalent to expecting natural selection to converge on restraint. There is no such attractor. Intensity, efficiency, and immediacy dominate whenever they are rewarded.

The same logic applies to gambling. Legalization did not manufacture risk‑seeking behavior. It removed barriers that previously obscured it, converting underground or offshore activity into visible, measurable participation.

If a policy is judged a failure because it exposes behavior that already existed, then the standard being applied is not empirical success, but aesthetic disappointment.

The Smuggled Concept of “Harm”

Critics routinely invoke “harm” as if its meaning were self‑evident. It is not.

In practice, the term oscillates between several incompatible notions: discomfort at visible vice, regret following poor choices, aggregate social unease, or deviations from middle‑class norms of self‑control. None of these constitute harm in a rigorous sense.

It is crucial to distinguish empirical harm claims from normative policy judgments. Data about emergency‑room visits, psychosis risk, or addiction prevalence are empirical facts. Declaring legalization a failure because such facts exist is a separate normative move that requires an explicit theory of agency and responsibility. Without that theory, the inference does not go through.

From an Axionic perspective, harm must be defined structurally: it is a net reduction of agency across future branches. Harm occurs when an intervention constrains an agent’s capacity to act, adapt, or recover — not when it merely permits actions that turn out badly.

Legalization does not coerce consumption. It does not mandate participation. It does not foreclose alternatives. It expands the option space while leaving choice intact.

Why Gambling Is the Hard Case (and Still Not a Failure)

Sports betting represents the strongest challenge to the general argument, and it is worth engaging seriously rather than rhetorically.

Unlike cannabis, modern betting platforms are deliberately engineered around ultra‑low latency feedback, variable reinforcement schedules, and seamless escalation. Losses can be recursive, leverage implicit, and recovery delayed. These properties can erode agency over time by impairing financial resilience and decision bandwidth.

This is not an argument against legalization per se. It is an argument about entrapment risk.

A critical distinction must be made between permitting error and engineering traps. Allowing an initial bad choice preserves agency. Designing systems such that an initial error predictably cascades into loss of control does not. The former respects adult moral status; the latter exploits cognitive vulnerability.

The appropriate response is not prohibition, which merely displaces the activity into less transparent channels. The appropriate response is agency‑preserving constraint: regulation aimed at mechanisms that convert voluntary risk into irreversible capture.

Such constraints include imposed friction and cooling‑off periods, hard loss and leverage caps, legible disclosure of expected value, and identity‑bound rate limits. These are not attempts to optimize outcomes. They are attempts to preserve recovery paths.

If a system predictably destroys agency, regulate the system. Do not criminalize the chooser.

“Casinos in Our Pockets” Is an Argument Against Modernity

The phrase “casinos in our pockets” is rhetorically effective precisely because it generalizes too well.

Smartphones place many high‑stimulation, habit‑forming systems within immediate reach: social media feeds, pornography, algorithmic trading apps, food delivery, and immersive games. Singling out gambling requires an unarticulated value judgment about which temptations adults may be trusted to resist.

Once generalized, the argument is no longer about gambling. It is about whether adults should be permitted unmediated access to temptation at all.

Negative externalities are real, but they do not justify collapsing agency at the source. When addiction or self‑destructive behavior harms others — dependents, partners, or victims of fraud — the ethical response is to protect those third parties directly through liability, guardianship, or restitution. It is not to preemptively revoke the chooser’s liberty absent demonstrated spillover.

A society that treats adults as perpetual risk‑management problems has already abandoned agency as a core value.

Liberalism Without Agency Is Just Soft Authoritarianism

A consistent pattern underlies these critiques:

Freedom is endorsed in principle.

Freedom produces messy, unequal, or embarrassing outcomes.

Freedom is reclassified as a mistake.

The implicit premise is that adults may be trusted only while they behave as model citizens, exercising restraint aligned with elite expectations.

This framing quietly conflates influence with coercion. Markets shape preferences, cultures transmit norms, and technologies amplify temptation. None of this negates agency. If influence alone invalidated choice, education, advertising, and language itself would be coercive.

Axionic ethics rejects this framing. Agency includes the right to err, to overindulge, to miscalculate, and to learn. A system that forbids error in order to prevent regret has already crossed into coercion.

If adults are not allowed to make stupid choices, they are not adults. And if liberty is withdrawn the moment it produces outcomes one finds distasteful, it was never liberty at all.

Postscript

Legalization did not fail.

What failed was a fantasy: that freedom could be granted without risk, that markets would self‑optimize toward moderation, and that agency could be expanded without exposing human fallibility.

Reality was always harsher than that. Freedom reveals preferences, amplifies incentives, and produces outcomes that are not curated for comfort.

The correct response is not prohibition by regret, but architectural clarity:

regulate mechanisms that systematically destroy agency

preserve choice where agency remains intact

accept that freedom includes outcomes you would not personally endorse

That is not a flaw of liberty. It is its cost.