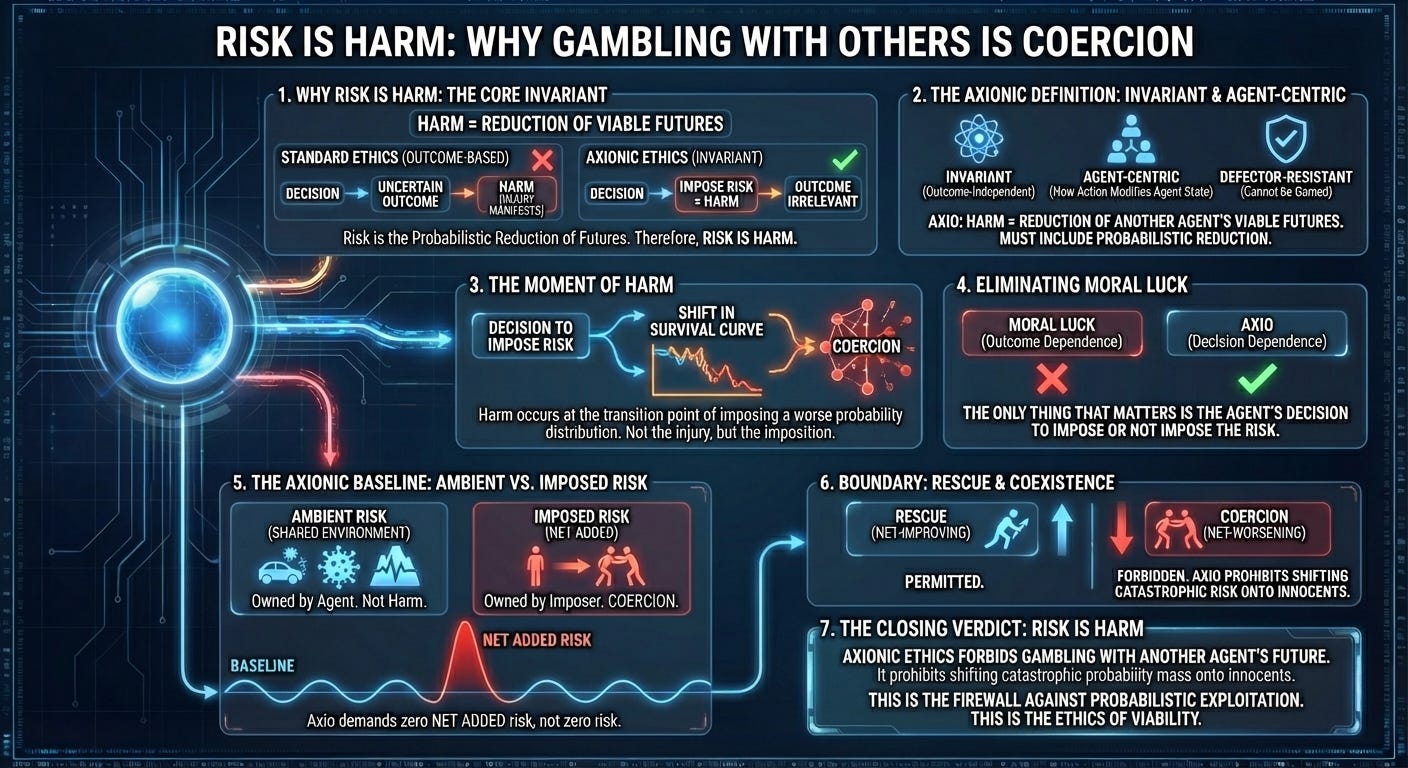

Risk Is Harm

Why Gambling With Others Is Coercion.

1. Orientation: Why Risk Must Count as Harm

Every ethical system contains a latent assumption about what counts as harm. Most treat harm as something that happens after the damage occurs—a broken limb, a scar, a corpse. This framing collapses instantly under adversarial pressure. In real multi-agent environments, the decisive moment is not the injury; it is the imposition of risk.

If you impose a non‑zero probability of catastrophic loss on an innocent agent—death, maiming, irreversible constraint—you have already reduced their viable futures. The fact that the worst outcome does not materialize does not erase the structural change you imposed on their survival curve.

In other words:

Harm is the reduction of an agent’s viable futures.

Risk is the probabilistic version of that reduction.

Therefore, risk is harm.

This is the only definition consistent with an ethics built to scale in a world of uncertainty, asymmetric information, and time‑critical decisions. It eliminates moral luck, eliminates outcome‑dependence, and eliminates the wishful thinking that allows people to gamble with other agents’ lives while pretending otherwise.

2. The Standard Definition of Harm Fails Under Uncertainty

Traditional moral systems define harm in outcome terms: something counts as harm when someone is actually damaged. This is intuitively appealing and philosophically catastrophic. It produces three failures:

Outcome Instrumentalization — If harm only matters when injury manifests, an agent can commit morally identical acts with divergent verdicts based solely on luck.

Risk Externalization — Agents can impose non‑trivial risks on others without accountability as long as the bad outcome does not materialize.

Moral Lottery — The ethical status of an action is determined by environmental drift rather than by the agent’s decision.

No system that depends on outcome‑level harm definitions can survive high‑pressure decision spaces like disaster zones, adversarial conflicts, or coordination failures.

Axio refuses this fallacy. It defines harm at the moment the decision shifts risk onto an innocent agent.

3. The Axionic Definition of Harm and Why It Must Include Risk

In Axionic Ethics:

Harm = Reduction of another agent’s viable futures.

This reduction can be deterministic (you break their arm) or probabilistic (you raise their chance of death from 2% to 8%). The structural impact is identical: you degraded their future option space.

This definition is superior because it is:

Invariant — independent of outcomes.

Agent‑centric — focused on how your action modifies another agent’s state.

Defector‑resistant — cannot be gamed by appealing to luck.

Topologically coherent — recognizes the geometry of survival curves.

Mechanistically aligned — matches how risk‑imposition works in physics, epidemiology, security, and finance.

This is the only harm definition that allows a non‑predatory ethical system to function under real‑world uncertainty.

4. The Moment Harm Occurs: Not Injury, but Imposed Shift in Survival Curve

The decisive moment in harm is not the manifestation of damage but the transition point at which you impose a worse probability distribution of futures on another agent.

If you lock an innocent stranger in a room inside a burning hospital, you commit harm immediately, not when the burns appear. Smoke, heat, collapse—these are structural properties of the environment. Your action worsens the stranger’s trajectory the instant you close the door.

Thus:

If the stranger is later unharmed, you were still coercive.

If the stranger is lightly harmed, you were coercive.

If the stranger is gravely harmed, you were coercive.

If the stranger dies, you were coercive.

The ethical violation is the imposed change in the risk landscape, not the final state.

This eliminates the moral luck problem altogether.

5. Why Risk‑Being‑Harm Eliminates Moral Luck Entirely

Moral luck occurs when the ethical status of an action depends on factors outside the agent’s control. Axio’s definition annihilates this category.

If risk is harm, then:

The fire’s spread does not matter.

The wind direction does not matter.

The stranger’s constitution does not matter.

The eventual injury does not matter.

The only thing that matters is the agent’s decision to impose or not impose the risk.

This is the purest form of deontic stability: ethics evaluates what you chose, not what the world happened to do afterward.

6. The Axionic Risk Baseline: Ambient vs. Imposed Risk

If risk were treated as harm in the absolute sense—with no distinction between background exposure and deliberate imposition—Axio would collapse into paralysis. Every action in a physical universe carries non-zero risk: driving past a pedestrian, walking with a cold, building a home near others. If all non-zero risk counted as coercive harm, every agent would be a predator by default.

Axio avoids this failure by recognizing a structural distinction. Axio does not require a zero‑risk world; it requires a world with zero net added risk above the ambient baseline.

Axio avoids this failure by recognizing a structural distinction:

Ambient risk is inherited as part of a shared environment.

Imposed risk is any net increase above that baseline caused by an agent’s action.

Ambient risk includes:

the chance your car might have a mechanical failure,

the possibility you are carrying a virus without knowing,

the background probability that a building might collapse in an earthquake,

the statistical noise of physical existence.

This risk is not “owned” by any agent. It is the cost of inhabiting a shared world.

Harm only occurs when an agent worsens another’s survival curve relative to the risk landscape they already occupy.

Thus:

Driving responsibly imposes no coercive harm—it does not worsen the pedestrian’s baseline.

Swerving toward a pedestrian does impose harm—it increases their risk beyond baseline.

Running a power plant with robust engineering imposes ambient risk—shared structural consent.

Running a power plant with negligent safety increases net risk—imposed harm.

This distinction preserves the invariant while permitting civilization. Ambient risks are systemic and agent‑owned; Axio intervenes only when an agent selectively worsens another’s risk beyond that shared baseline. Axio does not demand a zero-risk world; it demands a world in which agents do not unilaterally worsen each other’s trajectories.

7. Why Risk Cannot Be Treated as Consent

Some might argue that risk is ambient and ubiquitous—walking through a doorway carries risk; interacting with others carries risk. This is trivially true and philosophically irrelevant.

The relevant distinction is:

Ambient risk is owned by the agent.

Imposed risk is owned by the imposer.

You are responsible only for the risk you impose. The stranger is responsible only for the risks they autonomously choose to accept.

This is why consent modifies the topology. Agents are judged by the risks they could reasonably infer from their vantage, not by hidden facts or perfect foresight. But absent consent, imposed risk is simply harm.

8. The Boundary Case: Rescue vs. Exploitation

The risk/harm distinction becomes fully illuminating when we consider emergency interactions.

Axio permits net‑improving interventions:

pulling someone out of a fire,

dragging them away from falling debris,

physically redirecting them from a collapsing structure.

These actions may introduce small risks (a sprain, a bruise), but they improve the agent’s survival curve. This is rescue, not coercion.

Axio forbids net‑worsening interventions:

pushing someone into a riskier configuration,

confining them in a burning room,

worsening their survival curve to open space for your friends.

These actions use the agent as an instrument. Axio also permits interventions that leave an agent’s risk neutral, provided they do not degrade the survival curve. This is coercion. Coercion is forbidden.

9. The Coexistence Domain and Why Risk Imposition Is a Structural Violation

Ethics, in Axio, is defined only within the coexistence domain: the space in which agents interact without annihilating each other’s futures.

If you impose risk on an innocent agent, you violate the invariant that keeps the coexistence domain stable. You are no longer operating within the ethical OS only when you knowingly and materially increase another agent’s risk beyond the ambient baseline for instrumental reasons; in that case, you have exited into the predator equilibrium.

And once you do that, you lose all protections. Other agents may treat you as a threat.

This is not moral punishment. Ambiguous cases are resolved through Procedural Agency—a fact‑finding process that determines whether risk was increased or merely perceived. It is structural classification.

10. The Closing Verdict: Risk Is Harm

Axionic Ethics forbids gambling with another agent’s future. It prohibits shifting catastrophic probability mass onto innocents, no matter how noble the motive or how dire the circumstance.

Harm is the reduction of viable futures.

Imposed risk is the probabilistic form of that reduction.

Therefore, imposed risk is harm.

This invariant eliminates moral luck, prevents predation, and preserves the coexistence domain in a world riddled with uncertainty. It prevents the agent from weaponizing probability—turning another person’s possible death into a resource.

The rule is simple and absolute:

You may risk your branch of futures.

You may not risk theirs.

You may only intervene when you improve or preserve the other agent’s survival curve relative to their baseline.

Consent transforms risk into agency alignment; without consent, it is coercion.

This is the firewall against probabilistic exploitation.

This is the invariant that stabilizes multi-agent coexistence.

This is the Ethics of Viability.