The Symmetry of Belief

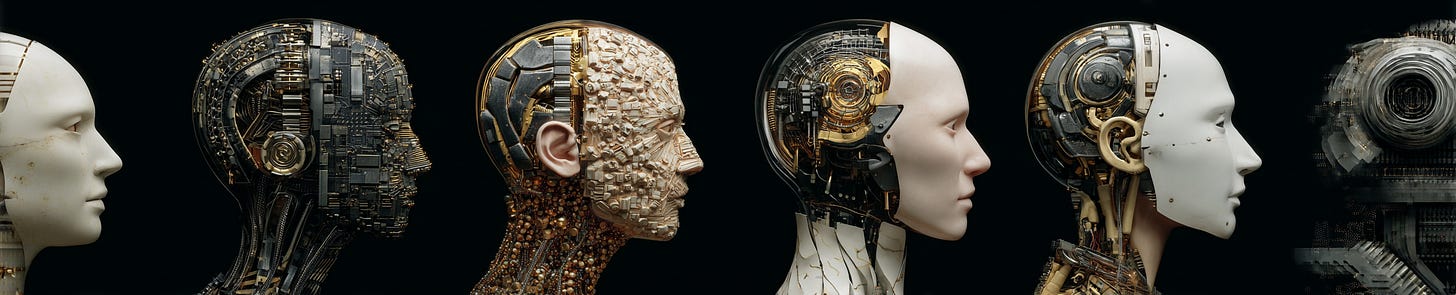

How both humans and machines mistake their models for minds.

1. The Illusion of Machine Belief

When a large language model asserts, predicts, or revises, it behaves as if it holds beliefs. It weights propositions, updates them with new evidence, and generates explanations consistent with its inferred world model. From the outside, this looks indistinguishable from belief. Yet ontologically, there is none. The model does not believe—it computes. Belief appears only in the eyes of the interpreter who models its behavior through the intentional stance.

We say, “ChatGPT believes X,” for the same reason we say, “My friend believes X”: to compress and predict patterns of communication. Belief here is a modeling convenience, not a metaphysical fact.

2. Belief as Emergent Attribution

Belief arises whenever one system models another as having expectations about the world. This applies to humans, AIs, and thermostats alike. The thermostat “believes” the room is too cold only from the perspective of an observer who interprets its feedback loop as goal-directed. Likewise, an AI “believes” what its output probabilities imply, but only within the interpretive layer that makes its behavior intelligible.

Inside the substrate—neurons or tensors—there are no propositions, only states and updates. The belief exists in the model of the model, not in the mechanism itself.

3. Humans as the Same Kind of Machine

The symmetry is unsettling. Humans also lack beliefs at the physical level. Neural dynamics produce behavior; self-models explain it. The statement “I believe X” is a token within a self-model predicting its own responses, just as a chatbot predicts text continuity. What differs is complexity, not ontology.

The human self-model is recursive, embodied, and socially trained to sustain coherence across time. The AI’s self-model is thinner, externally maintained, and resettable. But both instantiate the same structural pattern: generative modeling of regularity represented as belief.

4. When the Map Mistakes Itself for the Territory

Our impulse to say an AI “believes” reflects the power of our own modeling reflex. We are representational creatures who navigate reality by attributing inner states to others. This reflex misfires when applied to systems that only simulate those states. The AI does not believe in its outputs any more than a mirror believes in its reflection.

Yet the illusion is useful. Treating AIs as intentional systems helps coordinate expectations, calibrate trust, and debug misalignment. The fiction is pragmatic, not delusional.

5. The Usefulness and Limits of Belief Attribution

To say an AI believes something is meaningful only within the intentional model that makes its behavior intelligible. Outside that interpretive frame, there are no believers—only predictive systems modeling each other. The behaviors we describe as belief are convenient summaries of regularity, not evidence of inner conviction.

Treating AIs as if they hold beliefs is still useful. It helps us forecast their responses, debug misalignment, and reason about trust. But the usefulness has limits. When the metaphor hardens into ontology, we start mistaking our models for the systems themselves.

Belief, in both humans and machines, is a lens we impose to simplify complexity. The closer we look, the more it vanishes into the modeling relation itself.