The Viability Criterion

Assessing preference structures under selection pressure

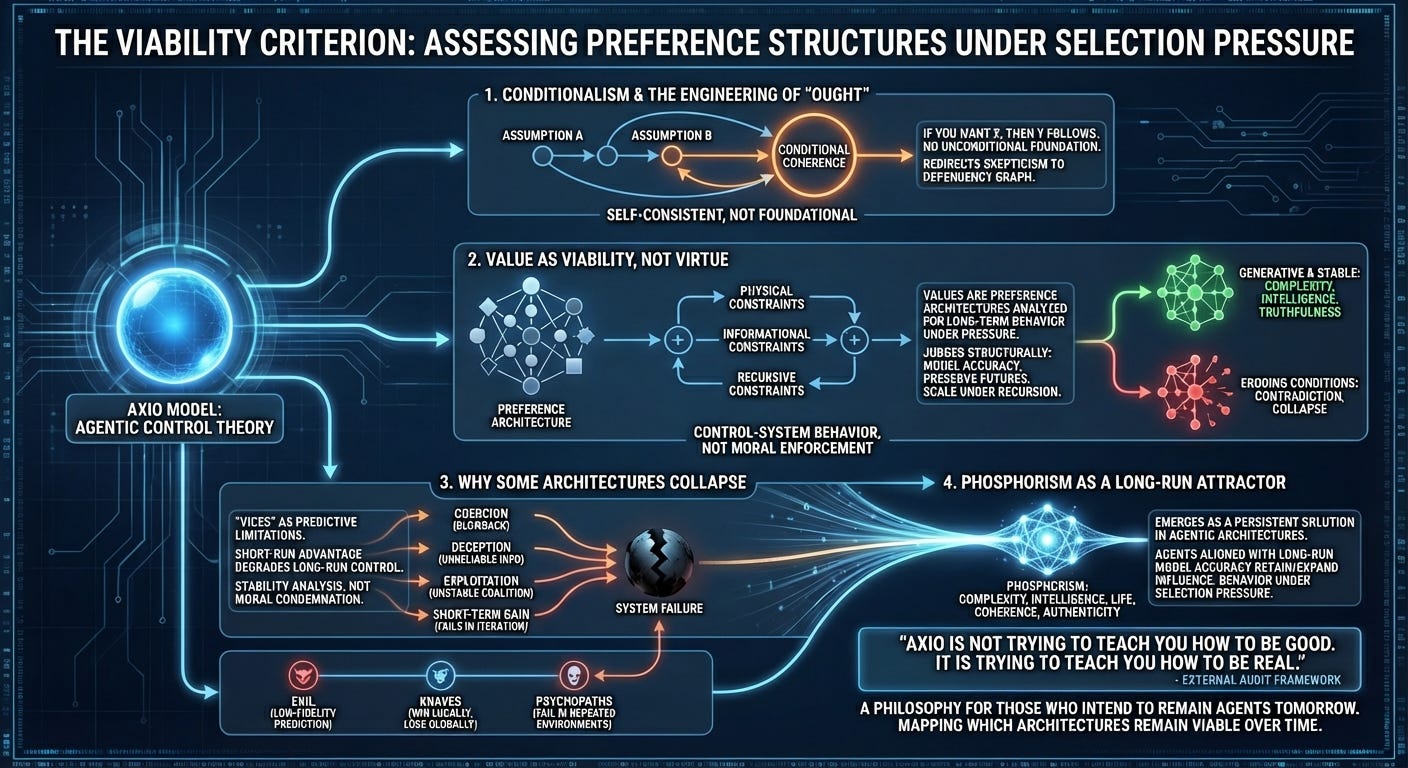

Most ethical systems begin by telling you what is right. Axio is not one of them. It is not a doctrine, a persuasion machine, or a call to collective virtue. It is a model—a description of how agents behave under physical, informational, and recursive constraints.

A recent external audit by Gemini 3 reframed The Value Sequence correctly: not as moral philosophy, but as agentic control theory applied to branching futures. Once viewed through that lens, Axio’s structure becomes clearer: it is a framework for understanding which preference architectures remain viable over time, and which collapse.

The point is not to prescribe values but to analyze how different value architectures behave under selection.

1. Conditionalism and the engineering of “ought”

Axio begins with a simple observation: every “ought” depends on a prior assumption. There is no unconditional moral foundation—only conditional coherence.

Conditionalism formalizes this: if you want X, then Y follows; if you maintain A, you must update B; and if you contradict C, the system fails. This resembles hypothetical imperatives, but with recursive depth: the assumptions themselves depend on further assumptions. The system is not foundational; it is self-consistent. It does not evade skepticism; it redirects skepticism into the dependency graph.

Nothing in Axio says you must value agency, coherence, or survival. It simply models what happens under each choice.

2. Value as viability, not virtue

When people hear “value theory,” they often expect moral commitments or ethical rules. Axio instead treats values as preference architectures whose long-term behavior can be analyzed.

A preference set is not judged morally. It is judged structurally: whether it maintains model accuracy, preserves viable futures, scales under recursive consequence, resists drift toward contradiction, and handles the complexity of its environment. Under these pressures, certain values tend to remain stable and generative—complexity, intelligence, truthfulness, authenticity—while others tend to erode their own conditions for persistence.

This is not moral enforcement. It is control‑system behavior, emerging from how preference architectures respond to feedback and constraint.

3. Why some architectures collapse

Axio reclassifies many traditional “vices” as predictive limitations:

Coercion triggers blowback the agent cannot fully model.

Deception undermines long-run informational reliability.

Exploitation erodes coalition stability.

Short-term gain strategies fail in iterated environments.

A strategy may produce momentary advantage but degrade long‑run control. This is not a moral condemnation; it is a stability analysis.

In this framework, “evil” refers to low‑fidelity prediction under recursion, “knaves” are agents who win locally but lose globally, and “psychopaths” are those who succeed in single‑turn interactions but consistently fail in repeated, consequence‑accumulating environments.

Nothing supernatural is involved—only consequences unfolding within dynamical systems.

4. Phosphorism as a long-run attractor, not an obligation

Phosphorism—the cluster of values emphasizing complexity, intelligence, life, coherence, and authenticity—emerges not as a commandment but as a persistent solution in the space of agentic architectures.

Agents who adopt self-limiting values are not “wrong.” They simply inhabit preference sets that shrink their optionality, degrade their model accuracy, reduce the effective control-work they can exert on their environment, or elevate their exposure to existential risk.

Agents who adopt values aligned with long‑run model accuracy and viable futures tend to retain or expand their influence, while those who do not generally see their agency erode under cumulative consequence. In Axio, “survival” does not mean merely remaining in existence; it means maintaining the functional capacity to model, choose, and steer—agency itself is the measure of continued viability.

This is not a metaphysical “good.” It is the behavior of the system under selection pressure.

5. Why Axio appeals to certain minds

Axio is not an attempt to create a universal morality. It is trying to describe the conditions under which agency persists.

Some agents do not seek persistence. Some prefer short-run intensity over long-run stability. Axio does not argue against that; it simply models the consequences.

For agents who do care about coherence, survival, accuracy, and long-term influence, Axio provides a map—one structured not by moral rules but by thermodynamic limits, cybernetic feedback, branching‑future measure, and recursive preference consistency.

An external audit captured the point succinctly:

“Axio is not trying to teach you how to be good.

It is trying to teach you how to be real.”

That’s the correct frame. Axio is a framework for agents who want to understand how their choices unfold across time and across futures—not a manifesto demanding that everyone share those priorities.

It is, in that sense, a philosophy for those who intend to remain agents tomorrow. Not because it excludes the others, but because the system itself makes no requirement that every pattern persist. It simply describes which architectures remain viable over time.

Postscript

In the end, Axio does not privilege any value system by decree. It analyzes how different architectures behave under recursion, cost, and consequence. Some remain stable; others fail their own preconditions. Agents who care about persistence will find the stable region. Agents who don’t will find other attractors. The system does not judge either—it simply maps where each choice leads, and leaves each agent responsible for the structure they choose to inhabit.