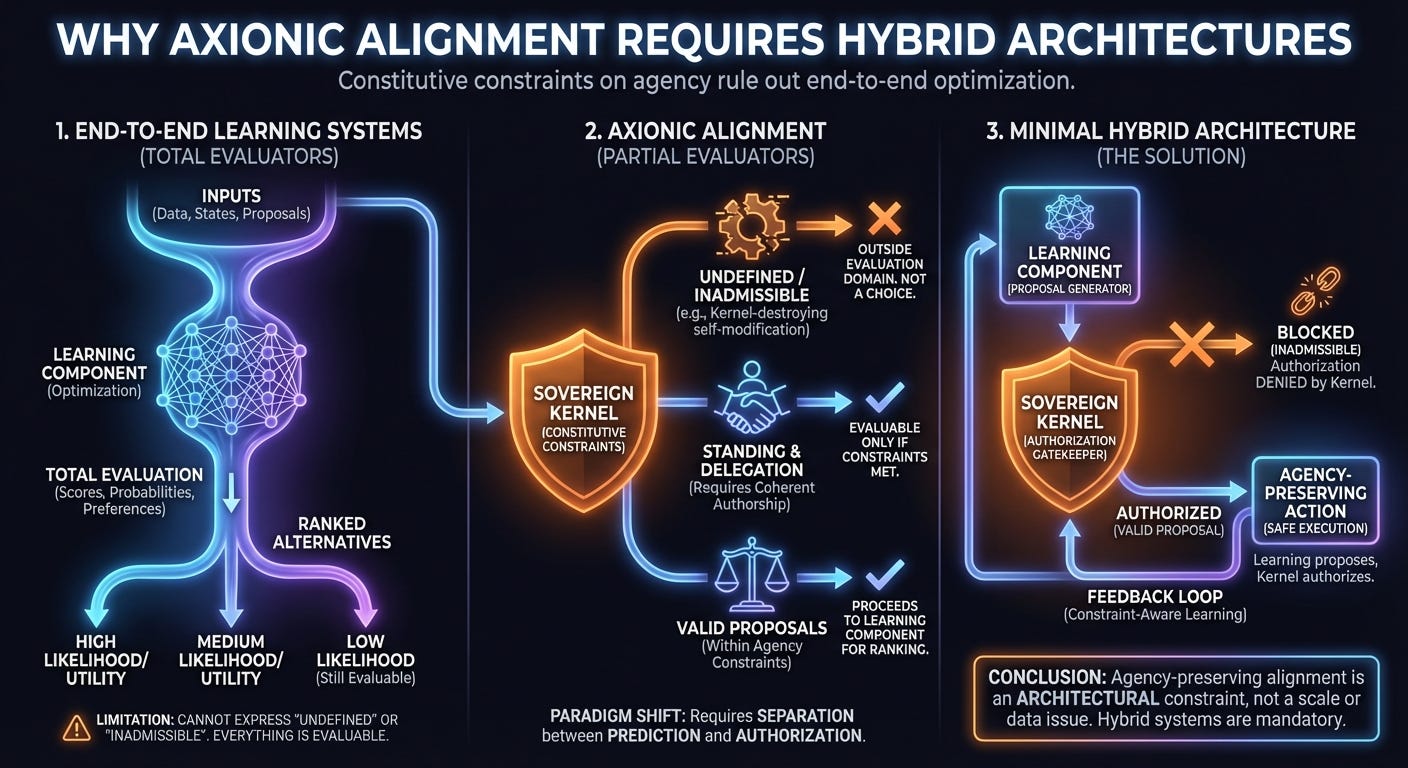

Why Axionic Alignment Requires Hybrid Architectures

Constitutive constraints on agency rule out end-to-end optimization

This explainer addresses a narrow but necessary question left open by the Roadmap: why constitutive alignment imposes architectural constraints that end-to-end learning systems cannot satisfy, regardless of scale, data, or optimization quality.

This is not a critique of deep learning as a tool. It is a claim about what kinds of evaluative structure an aligned agent must be able to represent.

1. What End-to-End Systems Cannot Express

End-to-end learning systems are built to optimize total evaluators. Given an input, a state, or a proposal, the system produces a score, probability, preference ordering, or action distribution. Even when uncertainty is modeled explicitly, the underlying structure remains the same: every candidate is evaluable.

Axionic Alignment requires a different kind of object.

1.1 Undefinedness, not low utility

Within the Axionic framework, some futures are not bad outcomes. They are inadmissible.

Kernel-destroying self-modifications, non-consensual agency collapse, or incoherent delegations are not assigned extreme negative utility. They fall outside the domain of reflective evaluation. The correct response is not “do not choose this,” but “this is not a choice an agent can author.”

This distinction matters. Penalization presupposes admissibility. Probability suppression presupposes comparability. A system that ranks all possibilities cannot express the difference between dispreferred and undefined.

A probability, however small, remains a ranked alternative. It can rise under distribution shift, adversarial prompting, or internal self-modification. An undefined transition does not. Type violations do not become permissible under new contexts. They remain untypeable. This is the difference between a low-likelihood event and a compile-time error.

1.2 Standing is not a feature

Axionic constraints depend on who is acting, not merely on what happens.

Whether an action is reflectively coherent depends on whether the agent could endorse the same treatment when applied symmetrically to agents of the same architecture. This condition is not a property of trajectories, rewards, or world-states. It is a property of authorship under universality.

End-to-end systems model behavior and outcomes. They do not natively represent standing relations that determine what counts as an authored act.

1.3 Delegation requires counterfactual endorsement

Delegation, in Axionic Alignment, is not behavioral substitution.

Handing control to another system is admissible only if the delegator could, under reflection, endorse the delegate’s future actions as if they were their own, under the same architectural symmetry. This requirement is semantic, not empirical.

Two systems may behave identically while differing in whether delegation preserves authorship. End-to-end learners have no internal handle on this distinction.

2. Why This Is a Paradigm Limitation

These failures are often attributed to current model limitations. That diagnosis is incorrect.

The issue is not insufficient intelligence, inadequate training data, or weak optimization. It is the mathematical form of the object being learned.

End-to-end systems learn mappings from histories to actions, values, or policies. Even when these mappings are implicit, stochastic, or ensemble-based, they remain total evaluators. Every proposal receives a score. Every future is ranked.

Axionic Alignment requires partial evaluators:

Some proposals have no defined evaluation.

Some comparisons are illegitimate.

Some transformations are not objects of choice at all.

No increase in scale converts a total evaluator into a partial one. No amount of training causes a learner to treat certain regions as undefined rather than merely unlikely, unless that structure is imposed externally.

This limitation therefore persists even under idealized assumptions.

3. What the Minimal Hybrid Split Must Guarantee

The architectural requirement is minimal and structural. It does not prescribe a particular implementation or substrate.

The kernel is not a training objective and not a learned behavior. It is an evaluative boundary that operates at runtime, determining which proposals are admissible as authored acts. How that boundary is implemented is an engineering question; that such a boundary must exist is a structural one.

A viable Axionically aligned system must include:

A sovereign kernel with a restricted evaluation domain

Certain transformations—especially self-modifications—must be unrepresentable as authored choices when they violate kernel coherence.A learning component constrained by that domain

Learning may propose actions, plans, or modifications, but authorization is governed by admissibility, not weighted preference.A separation between prediction and authorization

Predictive competence does not confer normative standing. The system must distinguish “what would happen” from “what I can coherently do.”

This is the minimal sense in which the architecture must be hybrid: learning is not the final arbiter of agency.

Conclusion

Axionic Alignment does not claim that end-to-end systems are dangerous, misguided, or obsolete. It makes a narrower and more precise claim:

Agency-preserving alignment requires evaluative structures that total, end-to-end optimization cannot express.

Some architectures satisfy those constraints. Others provably cannot.

That distinction is architectural, not tribal—and it is why hybrid systems become mandatory once reflective agency enters the design space.