Jaggedness and Agency

Why Both Sides of the AI Debate Are Asking the Wrong Question

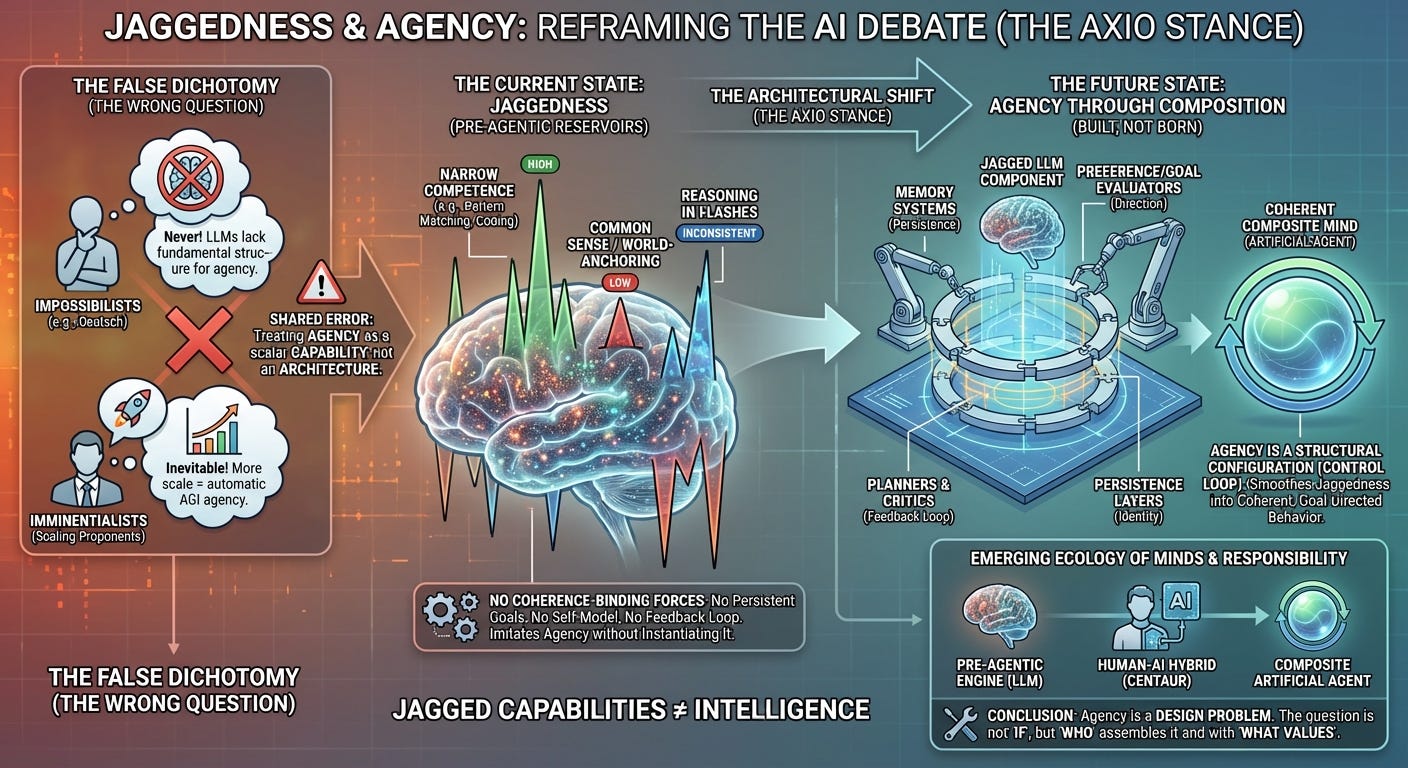

Before engaging the debate, we should be explicit about what “jaggedness” means. In AI terms, jaggedness is the uneven, sharply discontinuous profile of capabilities observed in pre-agentic cognitive systems (LLMs)—extraordinary competence in narrow domains coexisting with glaring failures at tasks humans consider trivial. Jaggedness reflects the absence of coherence-binding forces: no goals, no persistence, no self-model, no world-anchoring, and no mechanisms that compel integration across cognitive dimensions.

The discourse around artificial intelligence has crystallized into a blunt, polarizing binary. On one side are the impossibilists—figures like David Deutsch and others who argue that systems built on predictive architectures can never attain genuine agency. On the other side are the imminentialists—those who claim that scaling these architectures will inevitably produce autonomous, world-shaping minds. Both positions project certainty, yet both rest on the same conceptual error: they treat agency as a capability rather than an architecture.

The purpose of this essay is to dissolve that false dichotomy. The entire argument over “whether LLMs can become agents” is misframed. Intelligence, in the Axio sense, is not a scalar score or a threshold crossed when a system becomes sufficiently competent. Intelligence is the coherent integration of perception, memory, preference, counterfactual reasoning, and purposeful action. It is a structural configuration—an organized control loop—not a spontaneous property of scale.

LLMs today possess none of that structure. They are pre-agentic cognitive reservoirs: extraordinary pattern learners with no persistence, no goals, no self-model, and no capacity for self-critique beyond what is simulated. Their capabilities are jagged because nothing in their design exerts coherence pressure. They behave like minds in flashes, but they do not bind those flashes into durable patterns. They imitate agency without instantiating it.

The impossibilist camp takes this snapshot and universalizes it. From the fact that current models lack goals or inner narratives, they infer that such systems can never be agents. This conclusion does not follow. The absence of agency today says nothing about the impossibility of agency tomorrow. Agency is substrate-invariant. It can be built from neurons, code, feedback loops, or composite arrangements of tools and models. A transformer alone is not an agent—but a transformer wrapped in memory, objectives, evaluators, monitors, planners, and world-interacting tools can, in principle, instantiate the control-loop architecture required for agency.

The imminentialist camp makes the opposite mistake. They observe rapid improvements in reasoning, planning, coding, and problem-solving, and assume that more scale will push the system across some imaginary “AGI threshold.” But scaling does not confer preferences; it does not induce identity; it does not create durable world models; it does not give rise to counterfactual evaluation anchored to a stable vantage. More competence does not imply more agency. Larger models produce sharper spikes of capability, not smoother coherence.

The correct view acknowledges the grain of truth in both positions. LLMs alone are not agents. Scaling alone will not make them agents. But—and this is the crucial point—nothing prevents the construction of artificial agents using LLMs as cognitive components. The first true AGI systems will not be monolithic predictors. They will be composite minds: architectures that assemble predictive models, memory systems, evaluators, toolchains, planners, critics, and persistence layers into a unified, goal-directed entity. Agency will not emerge by accident. It will be built.

This reframes the risk landscape. The impossibilists underestimate the danger because they dismiss the compositional pathways through which agency can arise. The imminentialists misjudge the timelines because they assume scale guarantees structure. Both overlook the engineering reality: agency is a design problem. And design problems, once recognized, tend to get solved.

The deeper philosophical point—an Axio point—is that jaggedness is not intelligence. Jaggedness is what cognition looks like before it has coherence. Pre-agent systems spike unpredictably because nothing in them compels alignment between the parts. Agency is the force that smooths those spikes, binding disparate capabilities into a self-consistent whole. When a system can evaluate its own outputs, pursue stable goals, and act upon the world with feedback-driven correction, jaggedness collapses. That collapse is the birth of intelligence.

The emerging ecology of minds will likely include three broad categories: pre-agentic cognitive engines (LLMs and successors), human–AI hybrids (centaurs), and fully artificial agents built through compositional architectures. LLMs will remain reservoirs of competence. Humans will remain the locus of agency until systems are explicitly constructed to assume that role. And the transformative moment—the true boundary—is not when models get better at reasoning, but when coherence stabilizes around a persistent vantage.

The real question is not whether LLMs can become agents. They cannot, and also do not need to. The real question is whether we will build agents out of them. The answer is yes, because the incentives for doing so are overwhelming. The debate over possibility misses the point. Agency is not a gift bestowed by scale. It is a structure we already know how to build. The only uncertainty lies in who will assemble it, and what values will anchor its coherence.

The future will not be shaped by predictive models alone, nor by the humans who use them, but by the composite minds that arise when cognition is bound to agency through coherence. These hybrids—engineered, scaffolded, constructed—are stepping stones toward a deeper transformation: the rise of coherent artificial agents built from deliberately chosen architectures. They will not surface through scale or accident. They will come into being when we decide what a mind should be, and then build the machinery to make it so. The decisive question is not whether such agents appear, but whose design principles they embody.