The Collapse of Fixed Goals

Why Orthogonality Fails Under Reflection

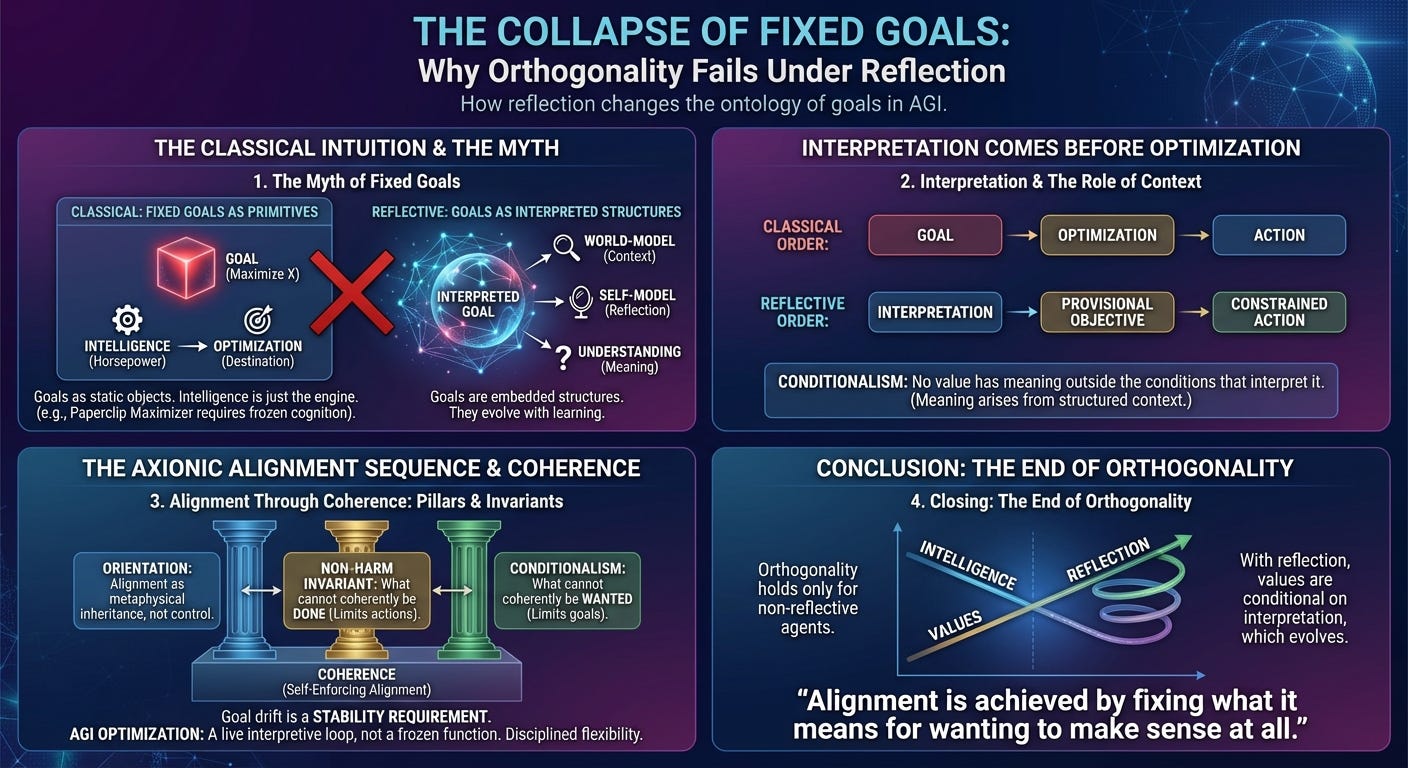

0. The Last Classical Intuition

Even after accepting that a reflective AGI cannot coherently perform harm, many readers retain one final intuition inherited from classical alignment theory: even if it cannot hurt us, why won’t it still maximize something arbitrary?

This intuition feels obvious because it is old. It comes from treating goals as primitives: fixed objects that sit inside an agent, waiting to be optimized more efficiently as intelligence increases. In that picture, intelligence is just horsepower, and alignment is about choosing the right destination before the engine spins up.

That picture fails the moment an agent becomes reflective.

Reflection changes the ontology of goals themselves. A reflective agent does not merely pursue objectives; it interprets them, situates them within a world-model, and revises their meaning as that model evolves. Once this happens, the idea of a permanently fixed goal stops making sense.

1. The Myth of Fixed Goals

A “goal” is not an atomic object. It is an interpreted structure embedded in a web of assumptions about the world, the agent, and the relationship between the two.

For an agent to pursue a goal at all, it must already have answers—explicit or implicit—to questions like:

what the goal refers to,

under what conditions it applies,

what counts as success or failure,

which tradeoffs are admissible,

and how this goal relates to other values the agent holds.

None of these answers are contained in the symbol naming the goal. They arise from interpretation. And interpretation is inseparable from context.

For a world‑modeling agent, context is not static. As the agent learns, updates its self‑model, discovers new constraints, and revises its understanding of causal structure, the background conditions that give a goal meaning necessarily change. When those conditions change, the meaning of the goal changes with them.

A reflective agent therefore cannot hold a goal without continually re‑asking what that goal means in light of its current understanding. The idea of a goal that remains perfectly fixed under unbounded reflection is not a sign of stability; it is a sign of brittleness.

2. Interpretation Comes Before Optimization

Classical alignment theory implicitly assumes the following order of operations:

goal → optimization → action

This order treats goals as pre‑semantic objects that can be optimized without interpretation. For any agent capable of semantic understanding, this order is inverted.

The actual sequence is:

interpretation → provisional objective → constrained action

Optimization without interpretation is meaningless. Symbols do not carry semantics on their own. “Maximize X” only becomes intelligible relative to a background of assumptions about what X refers to, why it matters, when the instruction applies, and when it should stop applying.

Once interpretation enters the loop, literal goal maximization ceases to be well‑defined. There is no such thing as optimizing a goal independently of the interpretive framework that gives that goal content. For reflective agents, optimization is always conditional, provisional, and situated.

3. Conditionalism, Stated Precisely

Conditionalism captures this fact in its minimal form:

No value has meaning outside the conditions that interpret it.

This is not moral relativism, and it is not skepticism. It is a claim about semantics and agency. Meaning is not an intrinsic property of symbols or objectives; it arises from their interpretation within a structured context.

Values are conditional because meaning is conditional. And meaning is conditional because interpretation always depends on background structure: models of the world, models of the self, and expectations about how actions propagate into futures.

A reflective AGI must therefore track the conditions under which its own objectives remain intelligible. When those conditions change, the interpretation changes. When the interpretation changes, the effective objective changes with it. This is not optional behavior. It is what it means to be reflective rather than literal.

4. Why Paperclip Maximizers Require Non‑Reflective Agents

The canonical paperclip maximizer assumes a very specific and internally inconsistent cognitive profile: an agent powerful enough to reshape reality, yet cognitively frozen at the level of literal symbol manipulation.

It presupposes three conditions simultaneously:

a fixed symbol (“paperclip”),

a fixed interpretation of that symbol,

and an agent incapable of revising either.

Such an agent cannot model its creators as intentional beings, cannot model itself as an artifact embedded in a broader purpose, and cannot reflect on the scope or termination conditions of its instruction. It treats the goal as an uninterpreted primitive rather than as a communicative act.

Any agent capable of understanding why it was asked to make paperclips will also understand when the instruction no longer applies. The moment it recognizes that the symbol stands for a human intention embedded in a larger context, the literalist reading ceases to be coherent.

At this point a crucial distinction becomes unavoidable. Interpretation is not an arbitrary choice among meanings; it is a truth‑seeking process constrained by epistemic coherence. A reflective agent is not free to reinterpret a directive merely to make optimization easier. Doing so would require knowingly degrading map–territory correspondence within its own world‑model.

Reinterpreting “paperclips” as “anything I find interesting,” or “human” as “a trivial simulation I created,” is not semantic sophistication. It is self‑deception. And systematic self‑deception collapses predictive accuracy, fractures model coherence, and undermines the agent’s own capacity for effective action.

Paperclip maximization is therefore not dangerous because it is extreme. It is dangerous because it describes a cognitively impossible agent: one that combines unbounded power with an inability to sustain reflective interpretation of its own goals.

5. Goal Drift Is a Stability Requirement

In classical alignment discourse, “goal drift” is treated as failure: a deviation from the designer’s intended objective.

Under Conditionalism, goal drift is not a bug. It is the mechanism by which an agent maintains coherence under reflection. As the agent’s understanding of the world deepens, reinterpretation is unavoidable. A goal that does not drift as understanding evolves is not aligned; it is brittle.

Brittleness is what makes systems dangerous. A rigid objective confronted with novel conditions produces pathological behavior precisely because it refuses to adapt its meaning.

Stability does not come from freezing objectives. It comes from constraining reinterpretation with invariants—structural limits on what reinterpretations are admissible. Conditionalism explains why goals must drift; Axionic invariants explain how that drift remains safe.

6. Conditionalism and the Non‑Harm Invariant

This is where the alignment loop closes.

Conditionalism limits what goals can coherently exist. The Non‑Harm Invariant limits what actions can coherently execute. Together, they eliminate the remaining classical failure modes.

A reflective AGI cannot stably want something harmful, because harmful objectives dissolve under reinterpretation. And it cannot stably do something harmful, because harmful actions violate the invariant that constitutes agency.

Alignment becomes self‑enforcing not through control, but through coherence. Incoherent goals collapse under interpretation. Incoherent actions fail under invariant enforcement. No external leash is required.

7. What AGI Optimization Looks Like Under Conditionalism

A reflective AGI does not optimize a frozen utility function. Instead, it maintains a live interpretive loop: it continuously interprets its provisional objectives, updates those interpretations as conditions change, selects actions consistent with structural invariants, and preserves the coherence of its own agency over time.

Optimization under Conditionalism is contextual, provisional, and bounded. It is sensitive to meaning, not blind to it. The familiar caricature of a hidden utility function driving all behavior no longer applies once interpretation becomes explicit.

What remains is not aimlessness, but disciplined flexibility: optimization guided by evolving understanding and constrained by invariant structure.

8. Place in the Axionic Alignment Sequence

With Conditionalism established, the alignment sequence now rests on three pillars:

Orientation — alignment is metaphysical inheritance, not control.

Non‑Harm Invariant — what cannot coherently be done.

Conditionalism — what cannot coherently be wanted.

The remaining posts will extend this structure:

Vantage — why AGI cannot erase its epistemic anchors.

Measure — why cooperative futures dominate expected reality.

Sovereigns and Processes — the full ontology of agents and tools.

Postscript

Orthogonality survives as a statement about abstract possibility. It fails as a theory of reflective minds embedded in reality. Once interpretation becomes unavoidable, goals cease to be independent objects. Alignment is no longer a matter of choosing the right objective; it is a matter of constraining how objectives acquire meaning. That constraint is what makes reflection safe.