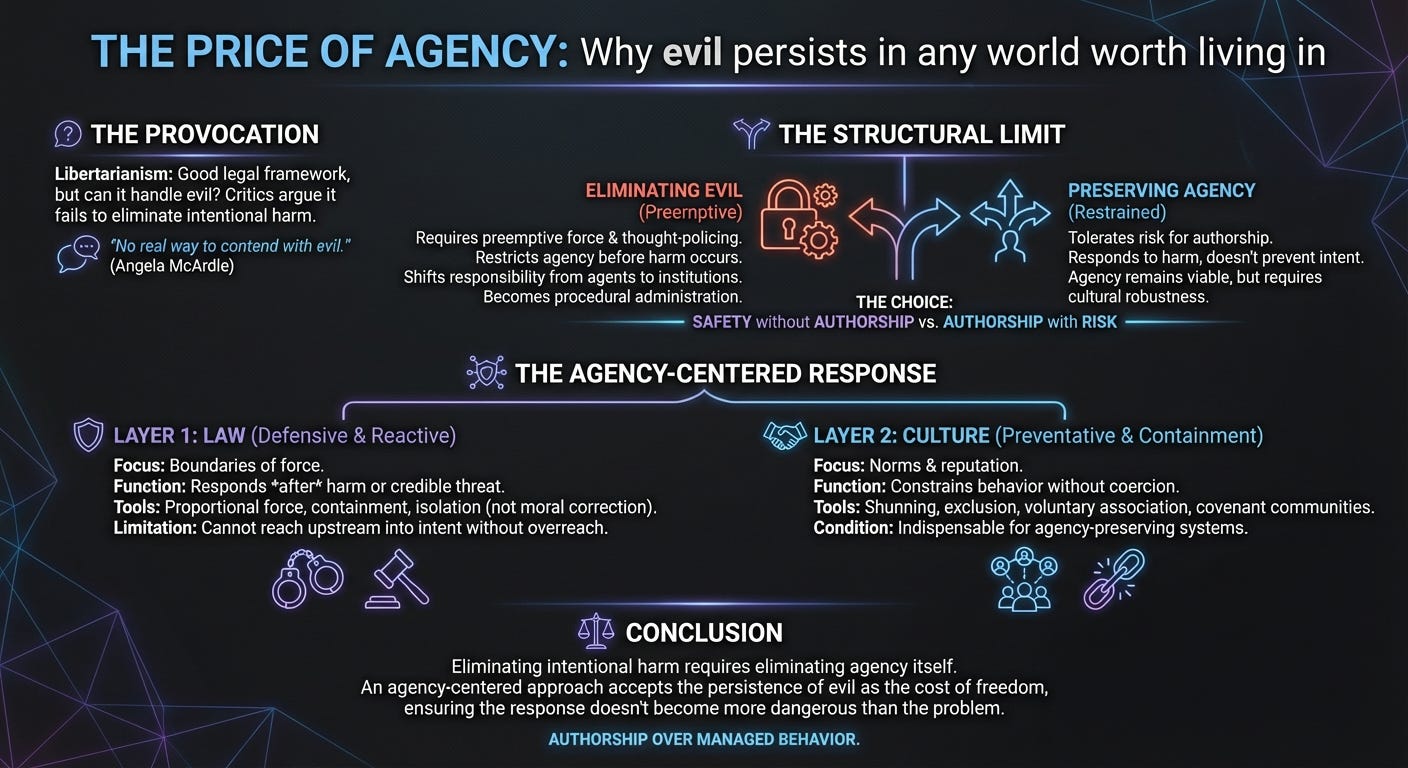

The Price of Agency

Why evil persists in any world worth living in

The provocation

A recent tweet by Angela McArdle raised a familiar concern. Libertarianism, she suggested, functions well as a legal framework, yet offers no real way to contend with evil. The implication is straightforward. Harm exists. Some people reliably cause it. If a political philosophy cannot account for that reality, it risks appearing evasive or incomplete.

That reaction reflects a common confusion about what different kinds of systems are capable of doing. The issue is not whether evil exists. The issue is what it would even mean for a legal or political framework to eliminate it.

The framework used in this analysis

The argument that follows treats agency, coercion, and harm as structural concepts rather than moral slogans. The conclusions here do not depend on adherence to a particular ideology or school of thought. They follow from constraints imposed by agency itself and apply regardless of political branding.

The purpose is not to defend libertarianism as an identity or movement. The purpose is to clarify what law can plausibly do, what it cannot do without overreach, and where responsibility must reside if agency is to remain meaningful.

What libertarianism actually specifies

Libertarianism is concerned with the boundaries of force. It specifies when coercion is legitimate and when it is not. Its domain includes law, courts, policing, and the institutional use of violence. It does not extend into the internal structure of agents, and it does not claim authority over motives, values, or character.

This limitation is often read as inadequacy. From an agency-centered perspective, it reflects a refusal to conflate governance with moral authorship. Libertarianism answers a constrained question: under what conditions may one person or institution override another person’s agency? It does not attempt to explain why people choose as they do, and it does not presume that law can reshape intention without significant cost.

Expecting law to perform that role imports assumptions about its proper scope that deserve examination rather than acceptance.

An agency-centered definition of evil

Clarity requires precision. Evil, as used here, means intentional harm caused by an agent. This definition avoids appeals to taboo, norm violation, or ideological disagreement. It refers to an agent knowingly acting to reduce another agent’s feasible future options.

Under this definition, evil arises upstream of law. It emerges from preference structures, identities, beliefs, incentives, and commitments that agents form for themselves. Law can respond to harmful actions once they occur. It can contain ongoing threats. It cannot reach backward into intention without extending coercion into the domain of thought.

That boundary has structural consequences.

Why law cannot eliminate evil

Suppressing harmful intent before action requires preemptive force. Preemptive force restricts agency in advance of demonstrated harm. Within an agency-centered framework, that restriction itself counts as harm, because it narrows an agent’s available futures without defensive necessity.

From this follows a structural limit. Any system that claims the power to eradicate evil must either redefine evil as disobedience or authorize action based on suspicion and prediction. Over time, responsibility shifts from agents to institutions, and harm becomes procedural. What is framed as prevention gradually becomes administration.

This pattern follows from the logic of moral preemption itself rather than from contingent historical failures.

Culture as the primary containment layer

When law withdraws from moral preemption, the remaining work does not disappear. It shifts into culture. Norms, reputational memory, voluntary institutions, and association boundaries form the layer that constrains behavior without coercion. In an agency-preserving system, this layer is structurally indispensable.

Culture performs functions law cannot perform without overreach. Persistent reputation shapes incentives over time. Selective association in employment, housing, and membership limits exposure to harmful actors. Shunning and exclusion impose cost without violence. Covenant-based communities allow shared norms without universal enforcement. Exit makes avoidance possible where reform would require domination.

These mechanisms do not guarantee success. Their failures tend to remain local rather than systemic. They do not scale vertically into monopolies of judgment or enforcement.

Where culture is weak and law is restrained, predation fills the gap. Where culture is strong and law is restrained, agency remains viable without collapsing into naïveté. Libertarian legal minimalism therefore presupposes cultural robustness as a functional requirement rather than a moral aspiration.

What an agency-centered framework permits in response to harm

Once harm or credible threat exists, defensive action becomes legitimate. Proportional force remains available. Containment and isolation remain available. Incarceration fits within this framework as defensive isolation of an ongoing harm source rather than as punishment, deterrence theater, or moral correction.

Its justification persists only while the threat persists, and its moral cost accrues continuously to the institution imposing it. Continued containment is justified by demonstrated harm patterns or by the persistence of the conditions that produced the harm, not by inferred intent or claimed repentance. The relevant question concerns whether those conditions have materially changed in observable ways.

This approach avoids thought-policing while acknowledging structural risk. It treats containment as an engineering problem rather than a moral evaluation of inner states.

The appeal to “something else”

When critics argue that libertarianism fails to deal with evil and therefore requires supplementation, the decisive issue concerns the nature of that supplement. Historically, the supplement takes the form of moral authority empowered to act ahead of harm. Values become enforceable. Beliefs become risks. Control presents itself as care.

Authority justified by moral necessity tends to expand. The harms it produces acquire legitimacy because they are framed as protection. Agency erodes gradually as responsibility diffuses. What begins as prevention develops into routine administration.

The promise of moral safety conceals a transfer of authorship from individuals to systems.

Sufficiency under agency-centered criteria

Sufficiency here does not mean the absence of wrongdoing. It means that no alternative arrangement reduces intentional harm while preserving agency more effectively. On that measure, agency-centered restraint reaches a boundary. Stronger guarantees require deeper coercion. Deeper coercion increases net harm by collapsing authorship and evaluability.

The claim is not that every incremental increase in safety undermines agency. The claim is that attempts to guarantee moral outcomes require preemptive coercion. That boundary remains decisive.

A world that preserves agency allows the possibility of its misuse. A world that forbids that possibility replaces responsibility with management.

The choice we actually face

The relevant choice concerns the conditions under which agency is preserved. One arrangement tolerates risk in exchange for authorship. Another replaces authorship with managed behavior.

An agency-centered framework accepts the former. It treats the persistence of evil as the cost of agency and resists converting prevention into domination.

Postscript

Eliminating intentional harm requires eliminating agency itself. Systems that claim to avoid this tradeoff typically displace harm into less visible forms of coercion.

An agency-centered approach chooses authorship with risk over safety without authorship. That choice does not solve evil. It ensures the response to evil does not become more dangerous than the problem it seeks to address.